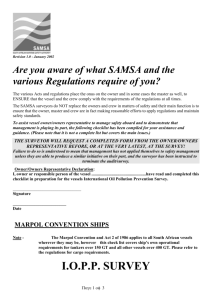

Prevention of pollution by oil

advertisement