Asian Transitions in an Ag' of Global Change

advertisement

,-;Asian Transitions in an

of Global Change

THINKINGHISTORICALLY:MeansandMotivesforOverseas

The Asian Trading World and the Coming of the Europeans

Expansion: Europe and China Compared

Fending Off the West: Japan's Reunification

Ming China: A Global Mission Refused

VISUALIZING THE PAST: The Great Ships of the Ming

Expeditions that Crossed the lndian Ocean

DOCUMENT: Exam Ouestions as a Mirror of Chinese Values

and the First Challenge

GLOBAL coNNEcTloNS: An Age of Eurasian Protoglobalization

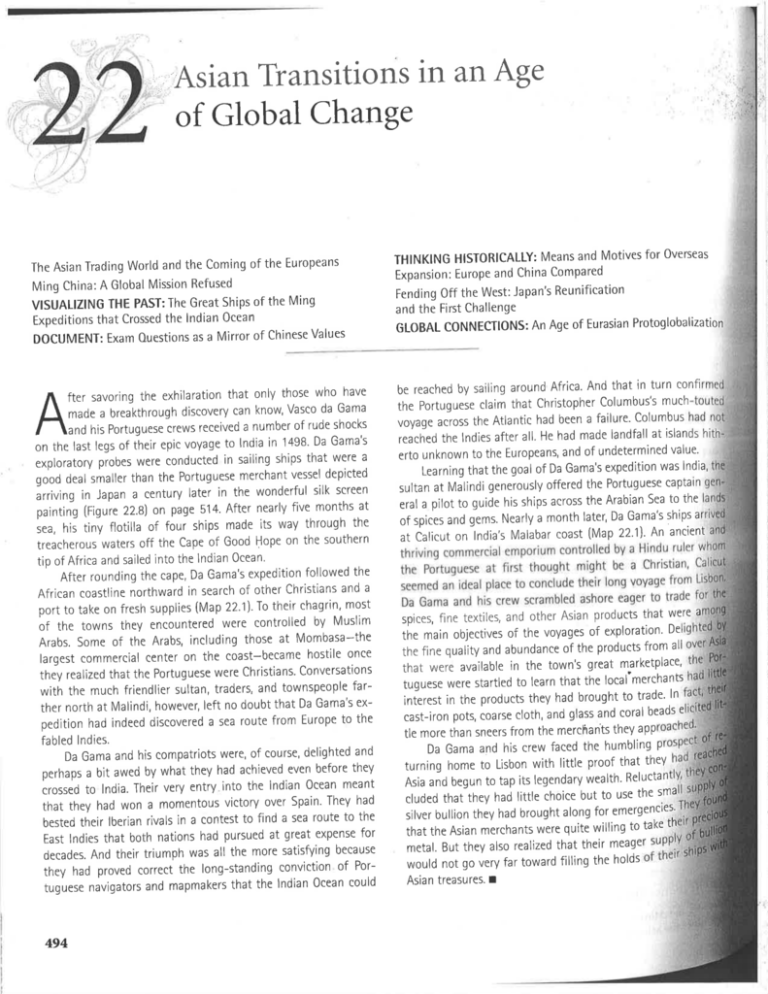

fter savorinq the exhilaration that only those who have

tt¿. , breithrough discovery can know' Vasco da Gama

A^

/-\ano

his Portuquese crews received a number of rude shocks

Gama's

on the last legs of their epic voyage to lndia in 1498' Da

were a

exploratory probes were conducted in sailing ships that

good deal smaller than the Portuguese merchant vessel depicted

ãrriving in Japan a century later in the wonderful silk screen

at

painting (Figure 22.8) on page 514' After nearly five months

the

sea, hii tlny notitta of four ships made its way through

southern

treacherous waters off the Cape of Good Hope on the

Ocean'

tip of Africa and sailed into the lndian

After rounding the cape, Da Gama's expedition followed the

a

African coastline northward in search of other Christians and

port to take on fresh supplies (Map 22'1)'Io their chagrin' most

of the towns they encountered were controlled by Muslim

Arabs. Some of the Arabs, including those at Mombasa-the

largest commercial center on the coast-became hostile once

they realized that the Portuguese were Christians' Conversations

with the much friendlier sultan, traders, and townspeople farther north at Malindi, however, left no doubtthat Da Gama's expedition had indeed discovered a sea route from Europe to the

fabled lndies.

Da Gama and his compatriots were'

of course, delighted

and

they

perhaps a bit awed by what they had achieved even before

meant

crossed to lndìa. Their very entry into the lndian Ocean

had

They

Spain'

over

victory

that they had won a momentous

the

to

route

a

sea

find

to

their lberian rivals in a contest

bested

Eastlndiesthatbothnationshadpursuedatgreatexpensefor

because

decades. And their triumph was all the more satisfying

theyhadprovedcorrectthelong-standingconvictionofPorcould

tuguese navigators and mapmakers that the lndian Ocean

494

Ag'

turn confi

be reached by sailing around Africa' And that in

the Portuguese claim that Christopher Columbus's much

voyage acioss the Atlantic had been a failure' Columbus

at islan ds hith

reacñed the lndies after all' He had made landfall

value'

undetermined

of

and

erto unknown to the Europeans,

lndia,

was

Lea rning that the goal of Da Gama's expedition

captain

sultan at Malindi genero usly offered the Portuguese

to the

Sea

Arabian

the

across

s

hips

gulde

his

eral a pilot to

a

of spices and gems. Near ly a month later, Da Gama's shiPs

ancient

(Map

An

22.1).

at Calicut on lndia's Malabar coast

fìne textiles, and other Asian prod ucts that were

Del

the main objectives of the voyages of exp loration.

all

from

products

the

the fine q uality and abundance of

sp ices,

that were available in the town's great marketplace'

tuguese w ere startled to learn that the local'merchants

ln

interest in the P roducts they had brought to trade'

cast-iron pots, coarse cloth, and gl ass and coral beads

tle more than sneers from the merc hants theY aPP

p

Da Gama and his crew faced the humbling

they

tu rni ng home to Lisbon with little proof that

Asia and begun to taP its legendarY wealth. Reluctan

the sma

cluded that theY had little choice but to use

silver bullion they had brought along for emergenctes'

to take th

that the Asian merchants were quite willing

metal. But they also realized that their meage

would not go very far toward fillìng ihe holds

Asian treasures.

r

e

a

we22.1

VascoDaGama'sarrival inCalicutonlndia'sMalabarcoastasdepictedinal6th-centu

ry European tapestry. As the pomp and

captured in the scene convey, Da Gama's voyage was regarded by European contemporaries

as a major turning point in world history.

of the enterprise that occupied the Europeans who went out to Asia in the

l6th and lTth cenwhich is one of the major themes of the chapter that follows, was devoted

to wor king out the

of that first encounter in Calicut. The very fact of Da Gama's arrival demonstrated

not

the seaworthiness of their caravel ships but also that the

Europeans'needs ancl curiosity could

them halfiaray around the world. Their stops at Calicut and ports

on the eastern coast of Africa

confirmed reports oF earlier travelers that the Portuguese

had arrived in east Africa and south

Asia long after their Muslim rivals. This disconcerting, discovery promised resistance

trading and emPlre building in Asia. It also meant major obstacles to their plans for

the peoples ofthe area to Roman Catholicism. The Portuguese

and the other Europeans

after them found that their Muslim adversaries greatly o'utnumbered

them and had longand well entrenched political and economic

connections from east Africa to the Philipwe shall see, they soon concluded that only

the use of military force would allow them to

caravels

Slender, long-hulled vessels utilized by

Portuguese; highly maneuverable and able to sajl

against the wind; key to development of portuguese trade empire in Asia.

the vast Indian Ocean trading system.

Da Gama's voyage marked a major turning point for western Europe, its impact

much less decisive. As was the case with the Mughal and

Safavid empires (see Chapter

themes in the histo ry of Asian civilizations in the 16th and lTth centuries

often

nothing to do with European expansion The

development of Asian states and empires

long-term processes rooted in the inner workings of these ancient

civilizations and

with neighboring states and nomadic peoples. Although the European

Prestn each of the areas considered in

this chapter, the impact of Europe's global expantmportance except in the islands of southeast Asia, which were especially

sea power. Most Asian rulers, merchants, and religious leaders

refused to

potential threat posed by what was, after all, a handful

of strangers from across

495

496

part

IV .

The Early Modern Period, 1450-1750: The world shrinks

'1350 c.E.

1500

1368 Ming dYnasty

comes to Power ln

China

1368-1398 Reign of

the Hongwu emperor

1390 Ming restrictions on overseas

commerce

1403-1424 Reign of

the Yungle emperor

1550

c.e.

c.E.

1600

1662-1722 Reign of

1755-1757 Dutch

Ashikaga shogunate

become paramount

1573-1620 Reign of

Portuguese EmPire

China

the Wanli emperor

in Asia;decline of

defeat combined

Muslim war fleet near

Diu off western lndia

573

End

of the

5B0s Jesuits arrive

1510 Portuguese

1

in China

western lndia

1590 Hideyoshi

1603 Tokugawa

shogunate established

tSll

unifies Japan

'1592 First JaPanese

banned in Japan

invasion of Korea

1619-1620 Dutch

597 Second JaPanese

invasion of Korea

established at Batavia

in China

'1405-1433 Zheng

He expeditions from

China to southeast

in lndia

1

1540s Francis Xavier

makes mass converts

power on Java; Oing

conquest

of Mongolia

Portuguese power

conquest of Goa in

peninsu la

170O c.E.

the Kangxi emPeror in

1

Portuguese

c.E.

1600s Dutch and

British assault on

1507 Portuguese

conquer Malacca on

the tip of Malayan

1650

c.E.

1614 ChristianitY

East lndia CompanY

on Java

1640s Japan moves

into self-imposed

Asia, lndia, and east

isolation

1641 Dutch capture

Malacca from

Africa

t49B-1499 Vasco da

Gama opens the sea

Portuguese; Dutch

route around Africa

confined to Deshima

to Asia

lsland

off

Nagasaki

1644 Nomadic

Manchus put an end

to Ming

dynastY;

Manchu Oing dynastY

rules China

The Asian Trading World and the Coming of the Europeans

t-\.

@¡I

centuries following Da Gama's

voyage, most European enterprise in the

lndian Ocean centered on efforts to find

the most profitable ways to carry Asian

products back to Europe. Some

Europeans went to Asia not

for personal

gain but to convert others to

Christianity, and these missionaries, as

well as some traders, settled in coastal

enclaves.

Trade Routes

to Asia

ffil

Africa, which

As later voyages bY Portuguese fleets revealed, Calicut and the ports of east

of. alarger

segment

a

small

onlY

uP

made

Asia,

Gama had found on the initial foray into

thousands

stretched

system

trading

This

commercial exchange and cultural interaction.

the

Both

from the Middle East and Africa along all the coasts of the massive Asian continent.

had

it

sailed

who

by

those

followed

routes

ucts exchanged in this network and the main

lished for centuries-in many cases' millennia'

In general, the Asian sea trading network can be broken down into three main

the west was

which was focused on major centers of handicraft manufacture (MaP 22.L). In

at the head of

zone anchored on the glass, carpets, and tapestries of the Islamic heartlands

dominåteá the central

Sea and the Persian Gulf. India, with its superb cotton textiles,

and silk textiles, formed

porcelain'

system. China, which excelled in producing paper,

centers were areas such

manufacturing

pole. In betlveen or on the fringes of the three great

port cities of east

the

and

the mainland kingdoms and island states ofsoutheastAsia,

the trading

products-into

forest

mainly raw materials-Precious metals, foods, and

and highest

demand

broadest

the

Of the raw materials circulating in the system,

day) and

present

(Shri

in

the

Lanka

paid for spices, which came mainlY from Ceylon

1'rade

the eastern end of what is today the Indonesian archip elago. Long-distance

stones'

precious

and

Africa,

high-priced commodities such as spices, ivory from

livestock,

ton textiles also were traded over long distances. Bulk items, such as rice,

in each

normally were exchanged among the ports within more localized networks

trading zones.

Since ancient times, monsoon winds and the nature

ments available to sailors had dictated the main trade routes

Chapter 22

.

Asran

Transitions in an Age of Global

Change

l.'i

Slovcs

Popci

Cold

Porcel¡in

Silk tcxrilcs

OlGswæ

Glusrvarc

Forest prcducLs

Carpcts

^t

JAPAN

Tcxtilcs

Hoßes

S¿¿

CHINÄ

Co(ton lcxtilcs

Gcms

EGYPT

Ctt

l.f

Silver

Hôngziou

ElephMls

S.lr

Cinlon

CHINESE ZONE

Mccca

INDIA

Itù)

PACI¡;]C

o.í

OCEAN

t)

AFRICA

cinÌmon

Euiror

.-

Ivory

ì

Forcst products

AniDìol hidcs

Cold

S

INDIAN OCEAN

lûvqs

ä=

Spiccs

Foest producls

Sofall

INDIAN ZONE

ARAB ZONE

t5m NtfLFl

t5m KtLoIlmR5

@

EE

El

fi

Major exports

Crucial choke points

Major ports

Major maritinre

trade routes

Sc¡lc îccúmlr for thr E(tualor

p

22.1

Routes and Major proclucts Exch anged ¡n the Asian Trading Network, c. I 500 By the early modern era

the ânc¡ent trading

that encompassed the lndian Ocean a nd neighboring seas from the Mediterranean to the North China sea

had expanded greatly in

volume of shipping and goods traded from the Middle

East to china as well as in the number of port c¡t¡es engaged in local and

nental commerce

the coasting variety that is, sailing along

the shoreline anå charting clistances and location

to towns and natural landmarks. The Arabs and Chinese, who had compasses and

well built ships, could, cross large expanses

of open water such as the Arabian and South

But even they preferred established coastal routes rather than the largely uncharted.

and

open seas. As the Portuguese quickly learned, there were several crucial polnts

of the trade converged or where geography funneled it into narrow areas. The

the Red Sea and Persian Gulf were two

of these points, as were the Straits of Malacca,

497

498

Part

IV '

World Shrinks

The Early Modern Period, 1450-1750: The

to the Encounter at Calicut

Trading EmPire: The Portuguese Response

Eco

governmeuts'prom

from other nations

mercantilists

ressed

mPorts

s

rn

order to improve tax revenues; popular during

the 17th md 18th centuries in Europe'

Portuguese

Church in

Southern lndia

H

over the centuries

bY the informal rules that had evolved

The Portuguese were not PrePared to abide

aPParent after the

It

was

great Asian trading complex.

for commercial and cultural exchanges in the

to exchange

silver,

and

gold

had little, other than

trip to the market in Calicut that the Portuguese

taught

mercantilists'

called

economic theorists'

with Asian peoPles. In an age in which Prominent

coffers,

his

in

had

a

monarch

amount of precious metals

that a state's Power dePended heavily on the

It was particularlY objectionable because it would

unthinkable.

was

a steady flow of bullion to Asia

from rival kingdoms and religions, including the

enrich and thus strengthen merchants and rulers

overseas enterPrises

had set out to undermine through their

Muslims, whose Position the Portuguese

presented, the PorAsia

to

for profit that a sea route

(Figure 22.2). Unwilling to forgo the Possibilities

theY could not get through fair trade.

tuguese resolved to take bY force what

from Asia reforce to extract spices and other goods

The decision bY the Portuguese to use

goods

trading

and

they could offset their lack of numbers

sulted largely from their realization that

junks,

no

Asian

for the huge war fleets of Chinese

with their suPerior shiPs and weaponrY. Except

Portuguese

the

of

the firepower and maneuverabilitY

people could muster fleets able to withstand

in Asian waters and their interjection of

sea

warfare into

squadrons. Their sudden aPPearance

intruders an element of surprise that kePt their

peaceful trading system gained the EuroPean

of empire building. The Portuguese forces were small

saries offbalance in the critical early Years

religious

after 1498 in their drive for wealth and

numbers but united at least in the early years

Asian

their

of the divisions that often separated

verts. This allowed them to take advantage

Da

when

their forces effectivelY in battle. Thus,

petitors and the Asians' inability to combine

on

in 1502, he was able to force Ports both

returned on a second expedition to Asian waters

tribute regime. He also assaulted towns that

African and Indian coasts to submit to a Portuguese

Figute 22.2 ln the

15th

a nd

1

was one of the

6th centuries, the port of Lisbon in tiny Portugal

exPloration' Although asPects of

of international commerce and European overseas

9

the earlY, strea

fore and

pictured here, additional square sails, higher

caravel design can be detected in the ships

of

stage

a

later

plify

in the shiPs' sides exem

numerous cannons Projecting from holes cut

aft

a

Chapter 22

.

Astan Transitions

in

an Age of Global

Change

4gg

fused to cooPerate. When a combined Egyptian and Indian fleet was finally sent in repr-isal

1509,

it was defeated off Diu on the western Inclian coast. The Portuguese woulcl not have to face so formidable an alliance of Asian sea powers again.

i¡

The Portuguese soon found that sea patrols and raicls on coastal towns were

not sufficient to

control the tracle in the items they wanted, especiaily spices. Thus, from 1507 onward they strove to

capture towns and build fortresses ¿ìt a number of strategic points on the Asian tradin! network

(see Map 22.2).In that year they took Ormuz at the southen.r end of the persian

Gulf; inlsto they

captured Goa on the western Indian coast. Most critical of all, in the next year they successfully

stormed Malacca on the tip of the Malayan peninsula. These ports served both as naval bases for

Portuguese fleets patrolling Asian waters and as factories, or warehouses where spices and other

products.could be stored until they were shipped to Ë,urope or elsewhere in Asia. Ships, ports, and

factories became the key components of a Portuguese trading empire that was financed and ofûcially directed by the kings of Portugal, but often actually controiled by portuguese in Asia and their

Ormuz

Portuguese factory or fortifieJ tradc

torvn locrtcd al soutl¡crn crri ol" l)ersi.rn Gulf; sile

for forcible cntry into Asian

sea trad€

Goa

Portuguese factory or fortifìerJ trrde low¡t

loc.rtecl on rvestcrn ludia coast; sjte lor [orcibje

ertry iDto Asian sea trade network

local allies.

The airn of the empire was to establish Portuguese monopoly control over key Asian prodparticularly

spices such as nutmeg and cinnamon (Figure zi.z).tdeally,all the spices p.oå.r..d

ucts,

be

shipped

to

in Portuguese vessels to Asian or European markets. There they would f e sold

were

at

high prices, which the Portuguese coulcl dictate because they controlled the suppiy of these goods.

('--

\.1

Classrvæ

CaqrcLr

JA,PAN

Tqdls

CHINA

Hosc

S¡lvcr

Colton tcxtilcs

Gcms

Elcphants

GtI

EGYgT

Pape¡

Srlr

Porccl¡in

Silk tcxl¡ls

Câlcutta

INDIA

PACIFIC

Iì:'

lltngtl

OCEAN

tj

AFRICA

\

Cinno¡lon

Equ¡tor

-

*)*

F

INDIAN OCEAN

AUSTRÂLIA

Imperial lrade

Imperial capitals

routes ln Asia

in Asia

=.1

$

E

I5M KILON{ETEßS

Scalc Âccurûtc

forthc Equalor

tsonuguese

Spanish

Durch

English

-

Major routes

f_E

6

t---l

El

Portuguese

Spanish

Dutch

English

Major ports

lhe pattern

of Early European Expansion in Asia The differing routes and choice of fortified outposts

adopted by

n nations as they sought

to tap directly into the lndian Ocean tradin g network reflect

greater

that

la te

the

network.

information regarding

comers, such as the Dutch and English possessed, relati ve to the pioneering Portuguese.

500

Part

IV '

Shrinks

The Early Modern Period, 1450-1750: The World

irnpose a licensing syster¡

The Portuguese also sought, with little success'-to

from Ormuz to

on all meichant ships that traclecl in the Inclian Ocean

Malacca.Thecombinationofmonopolyanclthelicensingsystem'backed

sizeable portion

was intendecl to give the Portuguese control of a

Uy

fo..",

of the Asian trading network'

Dutch

Portuguese Vulnerability and the Rise of the

ancl English Trading EmPires

up on paper never became

The plans for emP ire that the Portuguese drew

some of the flow of

control

to

reality. They managecl for sorne decacles

very limited areas.

in

grown

were

spices, such as nutmeg and mace, which

as PePPer and

such

concliments,

But a rnonoPolY of the market in keY

severe Punishto

resorted

cloves, eluded them. At times the Portuguese

ships' crews

and

traders

rival

the

ments such as cutting off the hands of

they simply

But

monopoly.

caught transPorting sPices in defiance of their

much less

monopolies,

their

clid not have the soldiers or the ships to sustain

discipline,

military

poor

rivals,

licensing system. The resistance of Asian

the

Portuguese shipping

ramPant corruPtlon among crown officials, and heavy

a heary toll on the

taken

had

losses causecl bY overloading ancl poor clesign

emplre by the end ofthe 16th century'

empire proved no

The overextended ancl declining Portuguese trading

it i'n

challenged

fleets

match for the Dutch and English rivals, whose war

short

in

the

least

at

early lTthcentury. Of the two, the Dutch emerged,

port and fortress

as the victors. TheY caPtured the critical Portuguese

on the

Batavia

aÍ

Malacca and built a new port of their own in 1620

sources

island

the

to

of |ava. The latter location, which was much closer

knowledge

EuroPean

k"y spices (see MaP 22.2), reflected the improved

the Dutch decision to

in the early

condiment'

a

minor

is

nutmeg

today

Atthougtr

22,3

Asian geograPhY. It was also the consequence of

Figure

manuscript

rather than on

ln

this

modern era it was a treasured and widely used spice'

centlate on the mo nopoly control of certain spices

being

are

nutmeg

an

oversized

lost the struggle

of

but

ustratio n from the 1 6th century, slices

t¡ade more generallY. The English, who fought I-rard

market'

international

the

on

India.

sale

to

for

weighed in preparation

control of the SPice Islands, were forcecl to fall back

as

uP of the same basic comPonents

The Dutch trading emPire (Map 22.2) was made

Batavia Dutch fo¡t¡ess located after 1620 on the

a

of

control

warshiPs on Patrol' and monoPolY

island of Java

Portuguese: fortified towns and facto ries,

numerous and better armed shiPs and went

more

had

Dutch

the

number of Products. But

extendsystem

Dutch

The

enpire

trading

Dutch

sYstematic fashion. To regulate the

the business of monoPoiY control in a much more

1n8 into Asia with fortihed towns and factories,

uprooted the plants that produced these sPlces

warships on patrol, and monopoly control of a

cloves, nutmeg, and mace, for example, they

products.

of

number

limited

removed and at times executed island

lands they did not control' TheY also forcibly

and dared to sell them to their trading

cultivated these spices without Dutch suPervision

EuroPe in the mid-17th centurY

Although the profits from the sale of these sPices in

run

that the greatest profits in the long

sustain Holland's golden age' the Dutch found

trading

themselves into the long-established Asian

trt6

i II

gained from peacefullY working

gain control over crops such as PePPer

mand for spices declined ancl their futile efforts to

In resPonse' the Dutch

grown in many places became more and more exPensive.

charged for transPorttng

mainly (as they had long done in EuroPe) on the fees theY

from buYing Asian

gained

profits

on

dePended

aiso

one area in Asia to another. TheY

in

areas for goods that could be sold

as cloth, in one area and trading them in other

their

although

flated prices. The English also adoPted these peaceful trading Patterns,

(discussed in

trade

cloth

cotton

the

and

on

India

of

were concentrated along the coasts

rather than on the spices of southeast Asia'

GoingAshore: European Tribute Systems inAsia

waY into the Asian trading

Their ships and guns allowed the EuroPeans to force their

and awaY from the sea, their

16th and 17th centuries. But as they moved inland

the

raPidlY disappeared. Because

and their abilitY to domina te the Asian PeoPles

t

Chapter 22

,

Asian Tiansitions in an Age of Global Change

50r

numbers of Asian armies offset the Europeans' advantage in weapons and organization

for waging

war on land, even small kingdoms such as those on lava and in mainland southeast Asia

were åble

to resist European inroads into their domains. In the larger empires such as those in Ct i.,u,-t-.r¿iu,

and Persia, and when confronted by martial cultures ,rr.h u, lapan's, the Europeans quickly

í"u.rr.d

their place' That they were often reduced to kowtowing or humbling themselves before the thrones

of Asian Potentates as demonstrated by the instructions given by abutch envoy about the proper

behavior for a visit to the Japanese court:

Our ministers have no other instruction to take there except to look to the wishes

of that brave,

superb, precise nation in order to please it in everything, and by no means

to think on anything

which might cause greater antipathy to us. . . . That consequently the Company,s

ministers frel

quenting the scrupulous state each year must abc ve all go aimed in modest¡

humility, courtesy,

and amit¡ always being the lesser.

In certain situations, however, the Europeans were drawn inland. away from their forts,

factories, and war fleets in the early centuries of their expansion into Asia. The Portuguese, and

the

Dutch after them, felt compelled to conquer the coastal areas of Ceylon to control the production

and sale of cinnamon, which grew in the forests of the southwest portions of that island. The

Dutch

slowly inland from their base at Batavia into the highlands of western

]ava. They discovered

this area was ideal for growing coffee, which was in great demand in Europe by

the 17th cenBy the

mid-l8th centur¡ the Dutch not only controlled the coffee-growing

power on Java.

areas

but were the

The Spanish, taking advantage of the fact that the Philippine Islands lay in the

half of the

the pope had given them to explore and settle in I 493,invaded the islands

in the 1560s. The

of Luzon and the northern islands was facilitated by the fact that the animistic

inhabitants

in small states the Spanish could subjugate one by one. The repeated failure

of Spanish expedito conquer the southern island of Mindanao, which was ruled by a single

kingdom whose

rulers were determined to resist Christian dominance, dramatically underscores

the limits

Europeans'ability to project their power on land in this era.

In each area where the Europeans went ashore in the earþ centuries

ofexpansion, they set up

regimes that closely resembled those the Spanish imposed

on the Native American peoples

New World (see Chaprer l9). The European overlords were

content to let the indigenous

live in their traditional settlements, controlled largely by hereditary

leaders drawn from

communities. In most areas, little attempt was made to interfere

in the daily lives of the

peoples as long as their leaders met the tribute quotas

set by the European conquerors.

was paid in the form of agricultural products grown by the

peasantry under forced

supervised by the peasants'own elites. In some cases, the

indigenous peoples contincrops they had produced for centuries, such as the bark

of the cinnamon plant. In

new crops, such as coffee and sugar cane, were

introduced. But in all cases, the demands

took into account the local peasants'need to raise

the crops on which they subsisted.

Lurcn

No¡thern islaird of pltilippines; conquered

by Spain during the 1560s; site

Mindmao

Southe¡n island of philippines; a

Muslim kirgdom that was al¡le to successfully resist

Spanish conquest.

the Faith: The MissionaryEnterprise in south

and southeastAsia

setbacks, of all the

Asian areas where European enclaves were established in the

expansion, India

appeared to be one of the most promising fields for religious

ofmajo¡ Cathàlic

missionary effort.

Æil

Jesuits in

lndia

502

Part

IV '

Shrinks

The Early Modern Period, 1450-1750: The World

St

Francis

Xavier, Jesuit

in lndia

Xavier,

Francis

Spanish Jesuit missionary;

worked in India in 1540s among the outcaste

and lower caste groups; made little headway

amoug elites.

di (1577-1656) Italian Jesuit missionary: worked in lndia during the early I ó00s;

introduced strategy to convert elites firstl strategy

Iater widely adopiéd by Jesuits in various parts of

Asia; mission eventuallY failed.

Nobili, Robert

and Dominican missionaries' as well as the Iesuit

conversion. From the 1540s onward, Franciscan

the poor' low-caste fishers and untouchables along

Francis Xaviet who were willing to minister to

Sut the missionaries soon found that they were

the southwest coast, converted tãns of thousands.

In fact' taboos against contact with untouchables

making little headway among high-caste groups.

for the missionaries to approach prospective

and other low-caste grorp, ,îu¿ã it .t.urly i-po.sible

upper-caste converts.

named Robert di Nobili devised a different conTo overcome these obstacles, an Italian Jesuit

Indian languages' including sanskrit' which

version strategy i" th. ;".it looor. rr. learned several

He donned the garments worn by Indian brahallowed him to read the sacred texts of the Hindus'

upper-caste

measures were calculated to win over the

mans and adopted a vegetarian diet. Atl these

Christianizin

Nobili reasoned that if he succeeded

Hindus in south India, ïhere he was based. Di

the lower Hindu castes into the fold' But' he arbring

then

ing the high-caste Hindu¡ they would

Indian

wa"s sophisticated and- deeply entrenched'

gued, because the ancient Éindu religion

listen ãnly to those who adopted their ways' Meat

brahmans and other trigh-.utt. grouPs irould

*t o were unfamiliar with the Hindus'sacred texts would be

eaters would be seen as äefiling; iho..

considered ignorant.

was undone by the refusal of high-caste

Despite some early successes, Di Nobili's strategy

and to give up many of their traditional beliefs

Hindu converts to worshiP with low-caste grouPs

particularlY the Dominicans and Franciscans, deand religious rituals. Rival missionary orders,

culture, theY claimed, Di Nobili and his

nounced his aPProach. In assimilating to Hindu

His rivals also pointed out that the

not the Indians' were the ones who had been converted.

untouchable Christians defied one of the

of di Nobili's high -caste converts to worshiP with

before God. His rivals finalþ won the ear of

tenets of ChristianitY: the equality of all believers

Deprived of his energetic ParticiPation

pope, and Di Nobili was forbidden to Preach in India'

quickly collaPsed, though he

India

south

in

knowledge of Indian waYs' the mission

India.

in

translate Indian texts and even tuaþ died

the conversion of the

Beyond sociallY stigmatized grouPs, such as the untouchables,

the greatest successes of the Christian

populace in Asia occurred only in isolated areas. PerhaPs

which had not previouslY been

Philippines,

the

sions occurred in the northern islands of

SPanish had conquered the island'

the

Because

a world religion such as Islam or Buddhism.

governed them as part of their vast

Luzon and the smaller islands Lo the south, and then

effort. The friars, as the Priests

misslonary

major

nental emPire, they were able to launch a

were called, became the

poPulace

rural

the

brothers who went out to convert and govern

friars fìrst converted Iocal FiliPino leaders'

channel for transmitting European influences. The

in

settlements that were centered, like those

leaders then directed their followers to build new

church, the residences of the

and the New World, on town squares where the local

to the spiritual needs of the

tending

BeYond

thers, and government offices were located.

their congregation, the friars served as government offìcials'

most FiliPinds were

Like the Native Americans of Spains New World emPire,

brand of

FiliPinos'

the

Americans,

verted to Catholicism. But also like the Native

religion

the

and

customs

and

of their traditional beliefs

sented a creative blend

taught

friars. Because keY tenets of the Christian faith were

that

corrupted if Put in the local languages' it is doubtfirl

Spanish dominance and

because

grasP of Christian beliefs. ManY adopted Christianity

embraced the new faith because

leaders' conversion gave them little choice' Others

or because they were taken with

illness

that the Christian God could protect them from

that they would be equal to their Spanish overlords in heaven.

seriouslY

Filipinos clung to their traditional ways and in the Process

Almost all

continued Public bathing,

Christian beliefs and Practices. The peoples of the islands

ritual drinking. TheY also

give

uP

to

sionaries condemned as immodest' and refused

in sessions that were

commune with deceased members of their families' often

European control was

where

area

recitations of the rosary. Thus, even in the Asian

of the Preconquest

much

greatest'

pressures for acculturation to European ways the

approach to the world was maintained.

Chapter 22

.

Asían Transitions

in

an Age of Global

Change

503

Ming China: A Global Mission Refused

ZhuYuanzhang, a military commander of peasant origins who founded the Ming dynast¡ had suffered a great deal under the Mongol yoke. Both his parents and two of his brothers had died in a

plague in 1344, and he and a remaining brother were reduced to begging for the land in which to

bury the rest of their family, Threatened with the prospect of starvation in one of the many famines

that ravaged the countryside in the later, corruption-riddled reigns of Mongol emperors ; Zhu alternated between begging and living in a Buddhist monastery to survive. When the neighboring countryside rose in rebellion in the late 1340s, Zhu left the monastery to join a rebel band. His .ou.ug.

in combat and his natural capacify as a leader soon made him one of the more prominent of several

rebel warlords attempting to overthrow the Yuan dynasty. After protracteã military struggles

against rival rebel claimants to the throne and the Mongol rulers themselves, Zhu's

"à.rquered most,of China. Zhu declared himself the Hongwu emperor in 1368. He reigned for 30 years.

Immediately after he seized the throne, Zhu launched an effort to rid China of all traces of

ar-i.,

the "barbarian" Mongols. Mongol dress was discarded, Mongol names were dropped by those who

had adopted them and were removed from buildings and court records, and Mongol palaces and

administrative buildings in some areas were raided and sacked. The nomads themselves fled or were

driven beyond the Great Wall, where Ming military expeditions pursued them on several occasions.

.Another Scholar-Gentry Revival

the Hongwu emperor, like the founder of the earlier Han dynast¡ was from a peasant famand thus poorly educated, he viewed the scholar-gentry with some suspicion. But he also realthat their cooperation was essential to the full revival of Chinese civilization. Scholars well

in the Confucian classics were again appointed to the very highest positions in the imperial

The generous state subsidies that had supported the imperial academies in the capital

the regional colleges were fully restored. Most criticall¡ the civil service examination system,

the Mongols had discontinued, was reinstated and greatly expanded. In the Ming era and the

that followed, the examinations played a greater role in determining entry into the Chinese

than had been the case under any earlier dynasty.

In the Ming era, the examination system was routinized and made more complex than before.

or county, exams were held in two out of three years. The exams were given in large comlike the one depicted in Figure 22.4, that were surrounded by walls and watchtowers from

the examiners could keep an eye on the thousands of candidates. Each candidate was assigned a

cubicle where he struggled to answer the questions, slept, and ate over the

several days that it

complete the arduous exam. Those who passed and received the lowest degree were eligible to

next level of exams, which were given in the provincial capitals every three years. Only the

and ambitious went on because the process was fi.ercely competitive-in some years as

4000 candidates competed for 150 degrees. Success at the provincial level brought a

rise in

opened the way for appointments to positions in the middle levels of the imperial bureaualso permitted particularþ talented scholars

to take the imperial examinations, which were

the capital every three years. Those who passed

the imperial exams were eligible for the highin the realm and were the most revered

of all Chinese, except members of the royal family.

Hongwu's Efforts to Root OutAbuses in Courtpolitics

mindful of his dependence on a well educated and loyal scholar-gentry for the day-toof the empire. But he sought to put clear limits on their influence and to instithat would check the abuses of other factions at court. Early in

his reign, Hongwu

position of chief minister, which had formerly been the

key link between the many

the central government. The powers

that had been amassed by those who occupied

transferred to the emperor. Hongwu also tried to impress

all ofÊcials with the honand discipline

he expected from them by introducing the practice of public beatings

found guilty of corruption or incompetence.

Offìcials charged with misdeeds were

the assembled courtiers

and beaten a specified number of times on their bare

aà:-"

@)il . restoration of ethnic Chinese

rule and the reunification of the country

under the Ming dynasty

(1

368-1 644),

Chinese civilization enjoyed a new age

of splendor. Renewed agrarian and

commercial growth supported a

population that was the largest of

any center of civilization at the time,

probably exceeding that of all western

Eu

rope.

eror in I368; originally

name Zhu yuanzhag;

e; restored

position of

504

Part

IV '

World Shrinks

The Early Modern Period, 1450-1750: The

took

the cubicles in which Chinese students and bureâucrats

for

cubicles

the

capital at Beijing. Candidates were confined to

the im perial civil service examinations in the

their own

surveillance of official proctors. They brought

constant

the

under

exams

days and completed their

or going

exams

the

taking

others

to

talking

ifthey were found

food, slept in the cubicles, and were disqualified

given'

outside the compound where the exams were being

Figu re 22.4 A 19th-century engraving

sh ows

in the ordeal' Those who survived never

buttocks. ManY died of the wounds theY received

was shared by all the scholarfrom the humiliation. To a certain extent' the humiliation

could be meted out to any of them'

virtue of the very fact that such degrading punishments

on the court factionalism and neverHongwu also introduced measures to cut down

earlier dynasties. He decreed that the emPeror's

conspiracies that had eroded the Power of

This was intended to Put an end to the Power

should come onlY from humble famiþ origins.

palace cliques that were centered on

ofthe consorts from high -ranking families, who built

eunuchs to occuPy Positions

fluential aristocratic relatives' He warned against allowing

within the Forbidden CitY. To

pendent power and sought to limit their numbers

established the practice of exiling all

against the ruler and fights over succession, Hongwu

in

and he forbade them to become involved

rivals to the throne to estates in the provinces,

some

hqd

he

when

as

thought control'

affairs. On the darker side, Hongwu condoned

forever from the writings included on

deleted

him

displeased

Mencius's writings that

went far to keeP Peace at court under Hongwu

exams. Although many of these measures

(r. 140 3 -l 424), theY were allowed to lapse under

strong successor, the Yungle emPeror

for the Ming EmPire.

pable, rulers, with devastating consequences

A Return to Scholar-Gentry Social Dominance

suffering made him sensitive to the

lot of the common

Perhaps because his lowlY origins and personal

imProve the

peasantry, Hongwu introduced measures that would

projects, including dike building

most strong emperors, he Promoted public works

To bring new lands

sion of irrigation sYstems aimed at imProving the farmers'Yields

it toiled so hard

lands

the

tion and encourage the growth of a peasant class that owned

would become the tax

production, Hongwu decreed that unoccuPied lands

forced labor demands on the

those who cleared and cultivated them. He lowered

Hongwu also Promoted silk and

the government and members of the gentrY class.

income for Peasant

duction and other handicrafts that Provided supplemental

Exam Questions as a Mirror

of Chinese Values

The subjects and specific learning tested on the Chinese civil service

exams give us insight into the behavior and attitudes expected of

the literate, ruling classes of what was perhaps the best-educated

preindustrial civilization. Sample questions from these exams can

tell us a good deal about what sorts of knowledge were considered

important and what kinds of skills were necess ary for those who aspired to successful careers in the most prestigious and potentially

the most lucrative field open to Chinese youths: administrative

service in the imperial bureaucracy. The very fact that such a tiny

portion of the Chinese male population could take the exams and

very few of those successfully pass them says a lot about gender

roles and elitism in Chinese society. In addition, the often decisive

role of a student's calligraphy-the skill with which he was able to

brush the Chinese characters-reflects the emphasis the Chinese

elite placed

on

a

refined sense ofaesthetics.

Question l: Provide the missing phrases and elaborate on the meaning of the following:

The Duke of She observed to Confucius: "Among us there was an

upright man called Kung who was so upright that when his father appropriated a sheep, he bore witness against him." Confucius said. . .

[The missing phrases are, "The upright men among us are not

like that. A father will screen his son and a son his father . . . yet up_

rightness is to be found in that."]

Question 2: Write an eight-legged essay [one consisting of eight

sections] on the foilowing:

Scrupulous in his own conduct and lenient only in his dealings

with the people.

Question 3: First unscramble the following characters and then

comment on the significance of this quotation from one of the clas_

sic texts:

Beginning, good, mutually, nature, basicall¡ practice, far, nea¡

men's

[The correct answer is, "Men's beginning nature is basically

good. Nature mutually near. Practice mutually far.,,]

QUESTIONS Looking at the content

we learn about Chinese society and

do the Chinese look for models to

of

What kinds of knowledge are

stress specialist skills or the sort of

broad liberal arts education?

Although these measures led to some short-term improvement in the peasants' condition,

were all but offset by the growing power of rural landlord families, buttressed by alliances with

in the imperial bureaucracy. Gentry households with members in government service were

from land taxes and enjoyed special privileges, such as permission to be carried about in

chairs and to use fans and umbrellas. Many gentry families engaged in moneylending

on the

some even ran lucrative gambling dens. Almost all added to their estates

either by buying up

held by peasant landholders or by foreclosing on loans made to farmers in times

of need in

for mortgages on their family plots. Peasants displaced in these ways had little choice but

tenants of large landowners or landless laborers moving about in search of employment.

land meant ever larger and more comfortable households for the gentry class. They jusgrowing gap between their wealth and the poverty ofthe peasantry by contrasting their

and industry with the lazy andwasteful ways of the ordinary farmers. The virtues

of the

were celebrated in stories and popular illustrations. The latter showed members of genhard at work weaving and storing grain to see them through the cold weather, while

who neglected these tasks wandered during the winter, cold and hungr¡ past the

and closed gates of gentry households.

levels of Chinese societ¡ the Ming period continued the subordination of youths

to

women to men that had been steadily intensiS,ing in earlier periods.

If an¡hing, Neowas even more influential than under the late song and Yuan dynasties. Some

proposed draconian measures to suppress challenges to the increasingly

rigid social

students were expected to venerate and follow the instructions of their teachers,

muddle-headed or tipsy the latter might be. A terrifring lesson in proper

decorum

an incident in which a student at the imperial academy dared

to dispute the findhis instructors. The student was

beheaded, and his severed head was hung on a pole

to the academy. Not surprisingl¡ this rather unsubtle

solution to the problem of

classroom merely drove student protest underground. Anonymous letters

Ptepared teachers continued to circulate among the

student body.

crit-

505

506

part

IV .

The Early Modern Period ,1450-1750: The world shrinks

subordination and, if

Women were also driven to underground activities to ameliorate their

despite Hongwu's

continued,

they

court,

the

At

they dared, expand their career opportunities.

were swayed by

Hongwu

as

such

rulers

able

Even

measures, to play strong roles behinâ the scenes'

chided the

Hongwu

occasion,

one

On

aunts.

and

the advice of favorite *i*, o, dowager mothers

that bereplied

She

people'

common

the

of

empress Ma for daring to inquire inio the condition

her

for

to be

proper

quite

it

was

thus

and

mother,

cause he was the father of the people, she was the

concerned for the welfare of her children'

Hundreds, sometimes thousands

Even within the palace, the plight of most women was grim.

that they would catch the emhope

in

the

ght to the court

elevated to the status of wife.

be

even

perhaps

ãncubines or

inactivity, just waiting for

and

in

loneliness

spent their lives

the emperor to glance their waY.

they could win within

In society atlatge, women had to settle for whatever status and respect

children and' when

male

on

bearing

the family. As before, their success in this regard hinged largely

-law to mother-in-law. The

these children were married, moving from the status of daughter-in

write by their parents or brothers,

daughters of upPer-class families were often taught to read and

(Figure 22.5)

and many comPosed Poetry, painted, and played musical instruments

degree of independence and

some

For women from the nonelite classes, the main avenues for

should be clearly distinformer

self-expression remained becoming courtesans or entertainers. The

were literate and

and

guished from prostitutes because theY served a very different clientele

lives of

enjoYed

often

accomplished in painting, music, and PoetrY' Although courtesans

for

men

of

upper-class

the most successful made their living by gratifying the needs

even

ited sex and convivial companionship.

An Age of Growth: Agriculture, Population, Commerce' and the Arts

growth in China that both

The first decades of the Ming Period were an age of buoyant economic

The territories

fed by and resulted in unprecedented contacts with other civilizations overseas.

Tang

dynasty. But in

the

trolled by the Ming emperors were trever as extensive as those ruled by

late Song

in

the

begun

Ming era, the great commercial boom and population increase that had

was given a

south

the

to

neweð and accelerated' The peopling ofthe Yangzi region and the areas

new food

of

intermediaries,

boost by the importation, through Spanish and Portuguese merchant

(

plants-maize

Three

from the Americas, particularþ root crops from the Andes higtrlands'

on

grown

be

could

crops

sweet potatoes, and peanuts-were especiaþ important. Because these

hilly and marginal

the

through

quickly

spread

cultivation

their

irrigation,

without

rior soils

to the

bordered on the irrigated rice lands of southern China. Theybecame vital supplements

regions'

southern

or millet diet of the Chinese people, particularly those of the rapidly growing

an

Because these plants were less susceptible to drought, they also became

the

behind

factor

against famine. The introduction of these new crops was an important

scene of court life. ln addition to court intrigues

Thevaried diversions of the wives and concubines of Ming emperors are depicted in this

games,

and polite conversation. With eunuchs, officia

music,

dance,

with

themselves

occupied

win the emperor's favor, women of the imperial household

yet well appointed spaces.

guards watching them closely, the women of the palace and imperial city spent most of their lives in confined

Figure 22.5

(c The Trustees of the Br¡tish Museum/Art

Resure,

NY.)

Chapter 22

.

Lsian Tiansitions in an Age of Global

Change

507

in population growth that was under way by the end of the Ming era. By 1600 the population of

China had risen to as many as 150 million from 80 to 90 million in the t¿ih century. i*ò centuries

later, in 1800, it had more than doubled and surpassed 300 million.

Agrarian expansion and population increase were paralleled in early Ming times by a renewal

commercial

growth. The market sector of the domestic economy became ever more pervasive,

of

and overseas trading links multiplied. Because China's advanced handicraft industries pioduced a

wide variety of goods, from silk textiles and tea to fine ceramics and lacquerware, whìch were in

high demand throughout Asia and in Europe, the terms of trade ran very much in China's favor.

This is why China received more American silver (brought by European merchants) than any other

in the world economy of the early modern period. In addition to the Arab

Ariun

"nà

traders, Europeans arrived in increasing numbers at the only two places-Macao and, somewhat

later and more sporadicall¡ Canton-where they were officially allowed to do business in Ming

China. Despite state-imposed restrictions on contacts with foreigners, China contributed significantly to the process of protoglobalization that was intensiSring cioss-cultural contacts world-wide

in the early modern era.

single society

Macao

One oftwo ports in which Europeans

rere permitted ro trade in China during the Ming

dynasty.

Canton One oftwo port cities in which Euro_

peans rere permitted to trade in China during the

Ming dynasty.

Not surprisingly, the merchant classes, particularly those engaged in long-distance trade,

profits from the economic l¡oom. But a good portion ãf th.i. gain-s was transferred

to the state in the form of taxes and to the scholar-gentry in the form of bribes for official favors.

reaped the biggest

Much of the merchants'wealth was invested in land rather than plowed back into trade or manufacturing, because land owning' not commerce, remained the surest route to social status in China.

Ming prosperity was reflected in the fine arts, which found generous patrons both at court and

the scholar-gentry class more generally. Although the monochromatic simplicity of the work

earlier dynasties was sustained by the ink brush paintings of artists such as Xu Wei, much of the

output was busier and more colorful. portraits and scenes of court, city, or country life were

prominent. Nonetheless, the Chinese continued to delight in depicting individual scholars or

contemplating the beauty of mountains, lakes, and marshes that dwarf the human observers.

Whereas the painters of the Ming era concentrated mainly on developing established techand genres, major innovation was occur-

in literature. Most notable in this regard

the full development of the Chinese novel,

had had its beginnings in the writings of

Yuan era. The novel form was glven great

@

by the spread of literacy among the

classes in the Ming era. This was faciliby the growing availability of books that

ASIA

from the spread of woodblock

from the lOth century onward. Ming

ARÀI'IA

PERS'A

Jidda

such as The Water Margin, Mo nkey, and

Lotus werc recognized as classics in

0

time and continue to set the standard

prose literature today.

and Retreat,

ofthe Europeans

boundless energy of the Chinese

of Ming rule drove them far beareas of expansion in centhe reglons south of the Yangzi.

In

the rhird Ming emperor, Yungle,

a series of expeditions that had

ur Chinese history. Between

1405

Zheng He, one of yungle's

led seven major ex(See Map 223

and Chaprer

of motives, including a desire

INDIA

ç

AFRICA

s

Boy

of

Ben

øl

g

&

Qt

ö'

.J

INDIAN OCEAN

E

Areas covered by

Zhenghe 14O5-1433

otm

MILS

tmKtLoÀrm

Map 22.3 Ming china and the Zheng He Expeditions, l405-1433 The composite view of

the Zheng He expeditions shown on this map indicate the great distances traveled as well as the

fact that most of the voyages hugged the familiar coastlines of southern Asia and East Africa

rather than risking navigation large expanses of open sea.

50E

Part

IV .

The Early Modern Period, |450-1750: The World Shrinks

Ricci, Matteo IrEnr chEE] (I552-1610) Along

with Adam Sctrall, Iesuit schola¡ in court oIMing

emperors; skilled scientist; won few converts to

Christianit¡

Schall, Adam (159I-1666) Along with Matteo

Ricci, fesuit scholat in court of Ming emperors;

skilled scientist; won feiv converts to Christianity'

to the wider world' prompted the

to explore other lands and proclaim the glory of the Ming Empire

voyages.

and.kingdoms Thelast

The early expeditions were confined largely to southeast Asia¡ 1e1

comparable

Africa-distances

of

coast

persia,

east

the

and

southern Arabia,

three reached as far as

The hunÆrica'

around

voyages

early

their

in

to those that would be covered by the Portuguese

exexpeditions

these

on

deployed

Past)

the

dreds of great ships (see the illustrations in Visualizing

centuries

fi'rst

of

the

in

China

of

power

and

emplified" the teJhnological sophistication, wealth,

Ming rule.

A Ming Naval

Expedition

Malteo Ricci's

Journals

expeditions in 1433' China's rulers

Nonetheless, in the decades after the last of the ZhengHe

overseas' and increasingly

presti^geand

power

purposely abandoned the drive to extend Ming

an emphasis on buildfrom

shift

The

world.

sought to limit and control contacts with the outiiãe

joining

the northern defense

and

repairing

i.rgîn. impressive fleets of the Zheng He voyages to

in policy and decichanges

key

these

works to form the Great Wall as we know it today reflected

sions about geopolitical orientation'

the Ming war fleet

In the centuries that followed the suspensio n of overseas expeclitions'

its ships, and strict

of

quality

and

declined dramaticallY in the number

with which a

masts

of

number

and

limits were placed on the size

priority

longstanding

the

to

return

seagoing ship might be fìtted. This

of defending against nomadic invasions eventually left China, and the

Indian Ocean world as a whole, vulnerable to European rncursions

by sea.

While the Chinese closed themselves in, the Europeans pro

to the

ever farther across the glo be and were irresistibly drawn

IL

,4i:iø.[¿<<at ! f.':

.',1,i ;, -42,,," ,¡'i"'ii""1'/"

Figure 22.6

6o/'"'

LC

Jesuits in Chinese dress at the emperor's court' The Jesuits

believedthatthebestwaytoconvertagreatcivilizâtionsuchasChinawasto

adopt the dress, customs, language, and manners of its elite' They reasoned

that once the scholar-gentry elite had been converted, they would bring the

rest of China's vast population into the Christian fold'

legendary of all overseas civilizations, the Middle Kingdom of

in additio n to the trading contacts noted earlier, Christian

ies infiltrated Chinese coastal areas and tried to gain access to

court, where theY hoPed to curry favor with the Ming emPerors.

to

religious orders such as the Franciscans and Dominicans toiled

modest

made

ancl

Progress

converts among the common PeoPle

the

could be counted in the tens of thousands, the Jesuits adoPted

(Figure

22'6)

India

in

down strategy that Di Nobiti had pursued

of a

China, howevet, a single person, the Ming em peror, instead

reason

that

for

and

caste, sat at the top of the social hierarch¡

the J

rulers and their chief advisors became the p rime targets of

mlssron.

Some Chinese scholars showed interest in Christian

and Western thinking more generallY. But the J esuit missionaries

made their waY to Beijing clearlY recognized that their

a

knowledge and technical skills were the keys to måintaining

elite

Chinese

the

at the Ming court and eventually interesting

tianity, Beginning in the 1580s, a succession of brilliant Jesuit

their

such as Matteo Ricci and Adam Schall, spent most of

forging

imperial cit¡ correcting faulty calendars,

Chinese

clocks imported from EuroPe, and astounding the

their

and

gentry with the accrlracy of therr instruments

dict eclipses. They won a few converts among the elite.

court officials were suspicious of these strange-looking

with large noses and hairy faces, and they tried to limit

with the imperial familY. Some at the court, especiallY

offìcials who were humiliated bY the foreigners'

calendars, were oPenlY hostile to the Jesuits. Despite

ment, however, the later Ming emperors remained

nated by these verY learned and able visitors that

handful to remain.

The Great Ships of the Ming Expeditions

that Crossed the Indian Ocean

In the early modern era Chinese ships for canal, river and ocean transportation improved significantly and their numbers multiplied many

times. By the fust decades of the Ming dynast¡ some of them had also

increased dramatically in size (see the image below). This trend was

given great impetus by the impressive series of expeditions that were

led by the eunuch Zheng He through island Southeast Asia and on to

coastal India and east Africa beginning in 1405. Some of the dragon

ships of Zheng Het fleet exceeded four hundred feet in length, thus

dwarfing the caravel Niña, one of the ships of Columbus's first voyage

to the Americas (see the image below). Chinese junks in this and earlier centuries were equipped with magnetic compasses, water-tight

compartments, and stern post rudders that would have allowed them

to navigate the open seas rather than simply following the coastlines of

the lands from which Zheng He and his crews sought to command

nibute and establish direct commercial relations.

Over the course of the seven expeditions led by Zheng iHe,

of these great treasure vessels accommodated tens of thouof sailors, merchants and soldiers. As the illustration below

clearly indicates, the largest Chinese junks were far larger than the

caravels, naos and other vessels that the portuguese, Spanish, and

rival Europeans deployed in their voyages of exploration and discovery from the 15th through the lTth century. They also dwarfed

the ubiquitous and swift Arab dhows that plied the waters of the Indian Ocean and adjoining seas. With such vessels the Chinese became for much of the fifteenth century a dominant force in Asian

seas east of the Malayan peninsula. The stout-walled chinese ships

also proved the only vessels in Asia that could stand up to the can_

non carried by the first waves of portuguese ships that sought to

dominate the Indian Ocean trading network.

ships

of this

size carry? Do

equipped with the naval

crossed the Pacifìc Ocean to the

to Europe? If not, why

"discover" and

and the Chinese Predicament

1500s, the

Ming retreat from overseas involvement had become just one facet of a faof dynastic decline. The highly centralized, absolutist political structure, which

established by Hongwu and had been run well

by able successors such as Yungle, beliability under the mediocre or incompetent men who occupied the throne

of the last two centuries of Ming rule. Decades of rampant official corruption, exgrowlng isolation of weak rulers by the thousands of eunuchs who gradually

within the Forbidden Cit¡ eventually eroded the foundations on which the

works proj ects, including the critical dike works

on the Yellow Rive¡ fell into disredrough t, and famine soon ravaged the land. Peasants in afflicted districts

were rethe bark from trees or the excrement of wild geese. Some peasants

sold their

to keep them from starving, and peasants in some areas resorted to cannibalism.

509

Means and Motives for Overseas

Expansion: Europe and China Compared

decades of the 14th centur¡ Chinese mariners dramatically demonstrated their

capacity to mount large expeditions for over-

In the early

tition on the part of the Europeans than the Chinese rulers could

even imagine. China's armies were far larger than those of any of

the European kingdoms, but European soldiers were on the whole

better led, armed, and disciplined. Chinese wet rice agriculture was

more productive than European farming, and

the Chinese rulers had a far larget populatio¡

to cultivate their fìelds, build their dikes and

bridges, work their mines, and make tools,

clothing, and weapons. But on the whole' the

technological innovations of the medieval period had given the Europeans an advantage

over the Chinese in the animal and machine

power they could generate-a capacity that did

much to make up for their deficiencies in

seas exploration and expansion. Because their

failure to sustain these initiatives left Asian waters from the Persian Gulf to the China seas

open to armed European interventions a century later, the reasons for the Chinese failure to

follow up on their remarkable naval achievements merits serious examination. The explanations for the Chinese refusal to commit to

overseas expansion can be best understood if

they are contrasted with the forces that drove

human power.

Despite their differences, both civilizations had the means for sustained exploration

and expansion overseas, although the Chinese

were ready to undertake such enterprises a few

centuries earlier than the Europeans. As the

the Europeans with increasing determination

into the outside world. In broad terms, such a

comparison underscores the fact that although

boththe Europeans and the Chinese had the means to expand on a

global scale, only the Europeans had strong motives for doing so'

The social and economic transformations that occurred in

European civilization during the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissànce had brought it to a level of development that compared

favorably with China in many areas (see Chapters 10 and 12)' A1though the Chinese empire was far larger and more populous than

tiny nation-states such as Portugal, Spain, and Holland, the European kingdoms had grown more efficient at mobilizing their more

limited resources. Rivalries between the states of a fragmented Europe had also fostered agreafer aggressiveness and sense ofcompe-

voyages of Da Gama, Columbus, andZhengHe demonstrated' both

civilizations had the shipbuilding and navigational skills and tech:

nology needed to tackle such ambitious undertakings.'vVh¡

were the impressive ZhengHe expeditions a dead end' whereas

more modest probes of Columbus and Da Gama were the

ning of half a millennium of European overseas expanslon

global dominance?

The full answer to this question is as complex as the

it asks us to compare. But we can learn a good deal by looking at

grouPs pushing

for

expansion

within each civilization

needs that drove them into the outside world. There

and

was

Rup acious local landlords built huge estates by taking advantage of the increasinglY

peasant population. As in earlier phases of dynastic decline' farmers who had been turned

land and tortured for taxes, or had lost most of the crops they had grown' turned to

ditr¡ and finally open rebellion to confiscate food and avenge their exploitation by

the Mingemperors; committed suicide i¡ 1644 in the face of a

|urchen capture ofthe Forbidden City at Beijing.

Chongzhen [chohng-jehn] Lastof

510

lords and corrupt officials.

Tiue to the pattern of dynastic rise and fall, internal disorder rçsulted in and was

Wall'

by foreign threats and renewed assaults by nomadic peoples from béyond the Great

the earþ signs of the seriousness of imperial deterioration was the inability of Chinese

and military forces to put an end to the epidemic of fapanese (and ethnic Chinese)

that ravaged the southern coast in the mid-16th century. Despite an official

Mongols early in the Ming era and with the Manchus to the northeast of the Great

times, the dynasty was finally toppled in 7644, not by nomads but by rebels from

time, the administrative apparatus had become so feeble that the last Ming emperor'

(chohng-jehn), did not realize how serious the rebel advance was until enemy soldiers

to

the walls of the Forbidden City. After watching his wife withdraw to her chambers

cide, and after bungling an attempt to kill his young daughter, the ill-fated Chongzhen

the imperial gardens and hanged himself rather than face capture'

spread support for exploration and overseas expansion in seafaring

European nations such as Portugal, Spain, Holland, and Englànd.

European rulers financed expeditions they hoped would bring

home precious metals and trade goods that could be sold at great

profits. Both treasure and profits coulcl l¡e translated into warships

and armies that would strengthen these rulers in their incessant

wars with European rivals and, in the case of the Iberian kingdoms,

with their Muslim adversaries.

European traders looked for much the same beuefits from

overseas expansion. Rulers and merchants also hoped that explorers

would find new lands whose climates and soils were suitable for

growing crops such as sugar that were in high demand and thus

would bring big profits. Leaders of rival branches of the Christian

faith believed that overseas expansion would give their missionaries

access to unlimited numbers of heathens to be convertecl or would

put them in touch with the legendary lost king, Prester lohn, who

would ally with them in their struggle with the infìdel Muslims.

By contrast, the Chinese Zheng He expeditions were very

much the project of a single emperor and a favored eunuch, whose

Muslim family origins may go a long way toward accounting for his

wanderlust. Yungle appears to have been driven by little more than

curiosity and the vain desire to impress his greatness and that of his

empire on peoples whom he considered inferior. Although some

Chinese merchants went along for the ride, most felt little need for

voyages. They already traded on favorable terms for all the

Asia, and in some cases Europe and Africa, could offer.

merchants had the option of waiting for other peoples to come

them, or, if they were a bit more ambitious, of going out in their

ships to southeast Asia.

The scholar-gentry were actively hostile to the Zheng He exThe voyages strengthened the position of the much-

hated eunuchs, who vied with the scholar-gentry for the emperor's

favor ancl the high posts that went with it. In addition, the scholargentry saw the voyages as a foolish waste of resources that the ernpire could not afford. They believed it would be better to clirect rhe

wealth and talents of the empire to building armies and fortifications to keep out the hated Mongols and other nomads. After all,

the memory of foreign rule was quite fresh.

As had happened so often before in their histor¡ the Chinese

were drawn inward, fixated on internal struggles and the continuing

threat from central Asia. Scholar-gentry hostility and the lack of enthusiasm for overseas voyages displayed byyungle's successors after

his death in I424led to their abandonment after 1430. As the Chinese retreated, the Europeans surged outward. It is difficult to exaggerate the magnitude of the consequences for both civilizations and

all humankind.

QUESTIONS How might history have been changed if the Chinese had mounted a serious and sustained effort to project their

power overseas in the decades before Da Gama rounded the Cape

of Good Hope? Why did the Chinese fail to foresee the threat that

European expansion would pose for the rest of Asia and finally for

China itselß Did other civilizations have.the capacityfor global expansion in this era? What prevented them from,launching expeditions similar to those of the Chinese and Europeans? In terms of

motivation for overseas expansion, were peoples such as the Muslims, Indians, and Native Americans more like the Europeans or

the Chinese?

Off the West: fapan's Reunifìcation

the First Challenge

g

Nobuaga, Oda (1534-1582) Japanese dairnyo;

first to make extensive use of firearms; in 1573 deposed last ofAshikaga shoguns; unifìed much

of

cent¡al Honshu unde¡ his command.

16th century the daimyo stalemate and the pattern of recurring civil war were so entrenched .z1i:\:

society that a succession of three remarkable military leaders was needed to restore f/a,\ mid-16th century the Japanese

\rlgÞè

internal peace. oda Nobunaga, the fìrst of these leaders, was from a minor warrior found leaders who had the military and

But his skills as a military leader soon vaulted him into prominence in the ongoing diplomatic skills and ruthlessness needed

for power among the daimyo lords. As a leader, Nobunaga combined daring, a willingness

to restore unity under a new Shogunate,

and ruthless determination-some would say cruelty. He was not afraid to launch a the Tokugawa. By the early 1600s, with

attack against an enemy that outnumbered

him ten to one, and he was one of the first of the potential threat from the Europeans

to make extensive use of the firearms that the

looming ever larger, the Tokugawa

Japanese had begun to acquire from the

\-/

in the 1540s.

Nobunaga deposed the last of the Ashikaga shoguns, who had long ruled in name