Market Power in the Breakfast Cereal Industry

advertisement

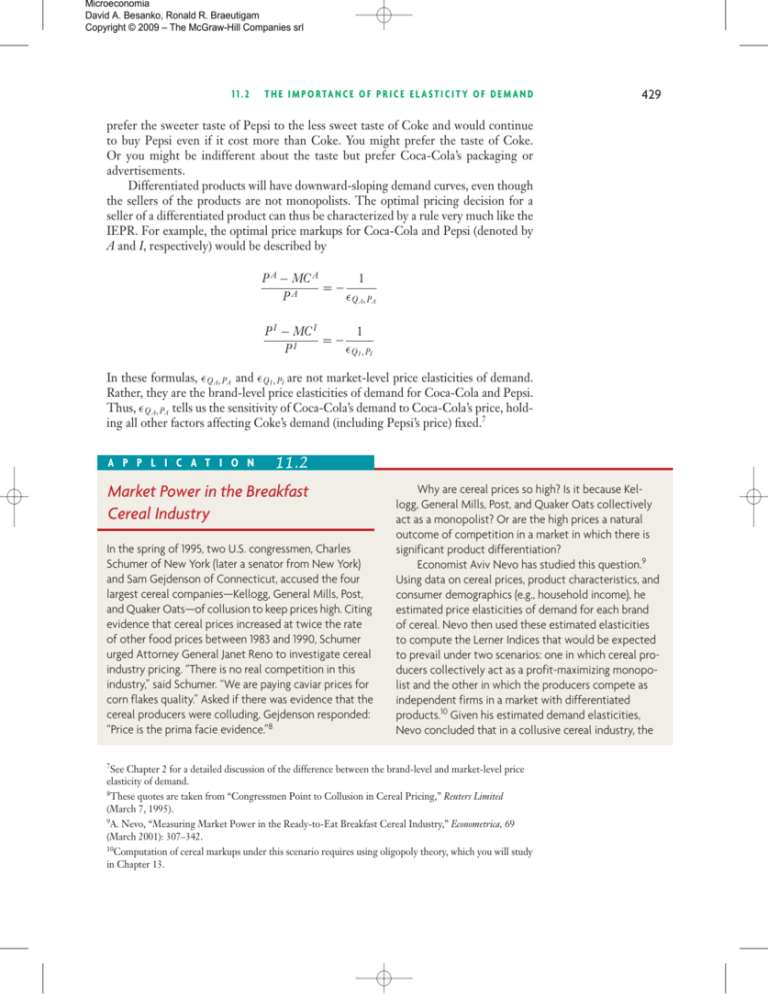

Microeconomia David A. Besanko, Ronald R. Braeutigam Copyright © 2009 – The McGraw-Hill Companies srl 11.2 T H E I M P O R TA N C E O F P R I C E E L A S T I C I T Y O F D E M A N D 429 prefer the sweeter taste of Pepsi to the less sweet taste of Coke and would continue to buy Pepsi even if it cost more than Coke. You might prefer the taste of Coke. Or you might be indifferent about the taste but prefer Coca-Cola’s packaging or advertisements. Differentiated products will have downward-sloping demand curves, even though the sellers of the products are not monopolists. The optimal pricing decision for a seller of a differentiated product can thus be characterized by a rule very much like the IEPR. For example, the optimal price markups for Coca-Cola and Pepsi (denoted by A and I, respectively) would be described by P A − MC A 1 =− PA Q A , PA P I − MC I 1 =− I P Q I , PI In these formulas, Q A, PA and Q I , PI are not market-level price elasticities of demand. Rather, they are the brand-level price elasticities of demand for Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Thus, Q A, PA tells us the sensitivity of Coca-Cola’s demand to Coca-Cola’s price, holding all other factors affecting Coke’s demand (including Pepsi’s price) fixed.7 A P P L I C A T I O N 11.2 Market Power in the Breakfast Cereal Industry In the spring of 1995, two U.S. congressmen, Charles Schumer of New York (later a senator from New York) and Sam Gejdenson of Connecticut, accused the four largest cereal companies—Kellogg, General Mills, Post, and Quaker Oats—of collusion to keep prices high. Citing evidence that cereal prices increased at twice the rate of other food prices between 1983 and 1990, Schumer urged Attorney General Janet Reno to investigate cereal industry pricing. “There is no real competition in this industry,” said Schumer. “We are paying caviar prices for corn flakes quality.” Asked if there was evidence that the cereal producers were colluding, Gejdenson responded: “Price is the prima facie evidence.”8 7 Why are cereal prices so high? Is it because Kellogg, General Mills, Post, and Quaker Oats collectively act as a monopolist? Or are the high prices a natural outcome of competition in a market in which there is significant product differentiation? Economist Aviv Nevo has studied this question.9 Using data on cereal prices, product characteristics, and consumer demographics (e.g., household income), he estimated price elasticities of demand for each brand of cereal. Nevo then used these estimated elasticities to compute the Lerner Indices that would be expected to prevail under two scenarios: one in which cereal producers collectively act as a profit-maximizing monopolist and the other in which the producers compete as independent firms in a market with differentiated products.10 Given his estimated demand elasticities, Nevo concluded that in a collusive cereal industry, the See Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of the difference between the brand-level and market-level price elasticity of demand. 8 These quotes are taken from “Congressmen Point to Collusion in Cereal Pricing,” Reuters Limited (March 7, 1995). 9 A. Nevo, “Measuring Market Power in the Ready-to-Eat Breakfast Cereal Industry,” Econometrica, 69 (March 2001): 307–342. 10 Computation of cereal markups under this scenario requires using oligopoly theory, which you will study in Chapter 13. Microeconomia David A. Besanko, Ronald R. Braeutigam Copyright © 2009 – The McGraw-Hill Companies srl 430 CHAPTER 11 M O N O P O LY A N D M O N O P S O N Y median Lerner Index of an individual brand would be 65 to 75 percent. In an industry with competition, the median Lerner Index of an individual brand would be 40 to 44 percent. How do these calculations compare to the actual Lerner Index in the cereal industry? According to Nevo, the actual Lerner Index for the cereal industry overall in the mid-1990s was approximately 45 percent. This is far below the Lerner Index you would expect to see if Kellogg, General Mills, Post, and Quaker Oats had colluded to fix prices. There is no denying that the Lerner Index in the cereal industry is positive, indicating that cereal firms enjoy market power. But the market power in the cereal industry seems to arise because brands of cereal are differentiated products, not because of collusion among manufacturers. QUANTIFYING MARKET POWER: THE LERNER INDEX market power The power of an individual economic agent to affect the price that prevails in the market. Lerner Index of market power A measure of monopoly power; the percentage markup of price over marginal cost (P − MC )/P. 11.3 C O M PA R AT I V E S TAT I C S F O R MONOPOLISTS When a firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve, either because it is a monopolist or ( like Coca-Cola) it produces a differentiated product, the firm will have some control over the market price it sets. For a monopoly, the ability to set the market price is constrained by competition from substitute products outside the industry. In the case of differentiated products, a firm’s direct competitors constrain its pricing freedom (e.g., Pepsi’s price limits the price Coca-Cola can charge). When a firm can exercise some degree of control over its price in the market, we say that it has market power.11 Note that perfectly competitive firms do not have market power. Because perfectly competitive firms produce at the point where price equals marginal cost, while monopolists or producers of differentiated products will, in general, charge prices that exceed marginal cost, a natural measure of market power is the percentage markup of price over marginal cost, (P − MC)/P (the left-hand side of the IEPR). This measure was suggested by the economist Abba Lerner and is called the Lerner Index of market power. The Lerner Index ranges from 0 to 1 (or from 0 to 100 percent). It is zero for a perfectly competitive industry. It is positive for any industry that departs from perfect competition. The IEPR tells us that in the equilibrium in a monopoly market, the Lerner Index will be inversely related to the market price elasticity of demand. As we’ve discussed, an important driver of the price elasticity of demand is the threat of substitute products outside the industry. If a monopoly market faces strong competition from substitute products, the Lerner Index can still be low. In other words, a firm might have a monopoly, but its market power might still be weak. N ow that we have explored how the monopolist determines its profit-maximizing quantity and price and the role that the price elasticity of demand plays in that determination, we are ready to examine how shifts in demand or cost affect the monopolist’s decisions. SHIFTS IN MARKET DEMAND Comparative Statics Figure 11.10 illustrates how a rightward shift in market demand affects the monopolist’s choice of price and quantity. In both panels, we assume that quantity demanded increases at all market prices (i.e., the original demand curve D0 and the new demand 11 Monopolists and sellers of differentiated products are not the only kinds of firms with market power, as you will learn in Chapter 13.