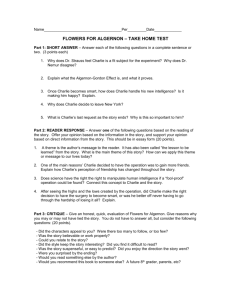

FLOWERS FOR ALGERNON By Daniel Keyes Progris riport 1

advertisement