Last Year's Identity Theft Bills Revised

advertisement

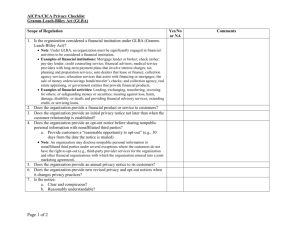

Analysis of the California Financial Information Privacy Act (“SB1”) by Leland Chan, General Counsel California Bankers Association The California Financial Information Privacy Act (“SB1”)1 was signed on August 27, 2003 and became effective July 1, 2004. The bill had failed to pass for three successive years, and was finally signed by former Governor Gray Davis as the industry removed its opposition after securing key concessions. Among these are: • • • • • more equal treatment as between information sharing with affiliates and with joint marketing partners. CBA consistently and vigorously opposed prior versions of the bill that disfavored joint marketing agreements, which are used more by smaller banks.2 elimination of a private right of action. protection of operational and transactional uses of customer information. more limited use of a separate state privacy notice. preemption of local privacy ordinances. Overview. The overall structure of SB1 is similar to the privacy provisions of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA). The key definitions largely track those in GLBA, except where noted.3 The GLBA distinction between customer and consumer is not made in SB1. However, the bill does not require an annual notice for a “one-off” purchaser of a product or service. If such a consumer’s information is to be shared, then the consumer must be furnished with the appropriate notice and option.4 Note that the helpful guidelines provided in GLBA regarding “stale” customer relationships (accounts that are inactive) are not included in SB1. 1 SB1 is codified in the California Financial Code, beginning with Section 4050. Unless otherwise noted, all references are to the California Financial Code. You may view this or any other California code at www.leginfo.ca.gov. 2 The broad GLBA definition of “financial institution” is used in SB1. In this Bulletin, unless otherwise indicated, the term “bank” may be used to refer to all covered financial institutions. 3 SB1does not include the specific GLBA carve-out for information that does not identify a consumer, such as aggregate information or blind data that does not contain personal identifiers. Nevertheless, even without a similar exception, it would be difficult to characterize such data, even under the state law, as personally identifiable. 4 Section 4053(d)(5). Two types of notices are contemplated—opt-out and opt-in. The sole opt-in requirement applies to disclosures of customer information to nonaffiliated third parties for the marketing of non-financial products and services. Information sharing among affiliates for marketing purposes and with nonaffiliated third parties pursuant to marketing agreements is generally subject to a consumer right to opt-out. However, if a bank does not share information outside the entity for marketing purposes, no California notice is required. No notice or consumer election applies to information sharing among wholly-owned, affiliated financial institutions that are in the same line of business when marketing products and services that share a common brand. There are also special allowances for joint employees of the bank and of the bank’s affiliate5 or nonaffiliated third party,6 and where customer information is maintained in information systems that are used in common by affiliated entities. CBA and coalition partners were able to ensure that the GLBA exceptions are included in the bill, so that non-marketing uses of information are not affected. Another key change in the final bill is the elimination of a private right of action to obtain civil penalties. Violations are subject to civil penalties of up to $2,500 per incident, but the right to enforce lies exclusively with the state attorney general and functional regulators.7 Nevertheless, private rights of action filed under the state’s Unfair Competition Law (Business & Professions Code Section 17200 et. seq.) are not necessarily foreclosed. Financial institutions may be subject to actions to seek injunctive relief and restitution based on alleged violations of SB1 (civil penalties may be sought pursuant to B&P Section 17206 only in government actions). At the time SB1 was passed, the affiliate sharing restrictions in SB1 were widely believed to be preempted by the Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”). The federal district court in Northern California so held last year in a case brought against Daly City and other municipalities, in which CBA participated as friend of the court. The court ruled that the FCRA preempted the financial privacy ordinances passed by the municipalities as to affiliate sharing, but not as to third party sharing.8 More recently, the district court in the Eastern District of California held that SB1 was not preempted by the FCRA, but indeed is specifically contemplated by the savings clause under GLBA. That decision is being appealed to the Ninth Circuit. Definitions and coverage The key SB1 definitions, including “nonpublic personal information (hereafter, “customer information” or just “information”), “financial institution,” and “affiliate” track those of GLBA. SB1 covers the disclosure of nonpublic personal information of California residents only.9 A bank is covered if it is “doing business” in the state. The case law on what constitutes “doing business” in California runs the gamut.10 5 Section 4052(d). Section 4052(e). 7 Section 4057. 8 Since the passage of SB1, which preempts local financial privacy ordinances, the municipalities took actions to repeal the ordinances. 9 A state resident is someone whose last known mailing address, other than an Armed Forces Post Office or Fleet Post Office address, as shown in the records of the financial institution, is located in California. Section 4052(f). 10 Consider, for example, West Corp. v. Superior Court (Sanford) (2004) 116 Cal.App.4th 1167, in which California jurisdiction was found where a California resident was permitted to sue an out of state telemarketer even though the defendant had no 6 Opt-in. The most touted provision of SB1 is one that the industry is perhaps least concerned over—opt-in for sharing customer information with non-affiliated third parties to market non-financial products.11 The opt-out form must be provided as a separate document (not incorporated with another document) and, to be effective, must be returned signed and dated by the consumer. The consent must clearly and conspicuously disclose: • • • • that by signing, the consumer is consenting to information sharing with the institution’s nonaffiliated third parties; that the consent will remain in effect until revoked or modified (which can be done at any time); the procedure for revoking consent; and that the bank will retain the consent (or a copy), that a copy is available upon request, and the consumer may want to keep a copy as a record. It is not necessary to identify the third party with whom information may or will be shared, or to describe specifically what information will be shared. Affiliate sharing Disclosures for marketing purposes. The SB1 restrictions on the sharing of customer information among affiliates apply only to marketing uses of information, and not to transactional or administrative uses. The definition of affiliate12 is the same as that used in GLBA. Note that banks retain the option to market, without restriction, the products and services of affiliates or nonaffiliated third parties to its own customers if the banks do not disclose customer information in the course of marketing. But the bank is still required to enter into a confidentiality agreement with a non-affiliated third party as to the use of the information received from, or gleaned from the application of, responding customers. The agreement must include the right by the bank to verify compliance by the other entity. Two different rules apply to affiliate sharing. The general rule is that a bank may disclose information to an affiliate for marketing purposes only after providing a notice annually that information may be shared and the consumer has not opted out. But, if the bank and the affiliate are in the same line of business,13 regulated by the “same” functional regulator, and the provided product or service shares a common brand as between the sharing entities, the notice and opt-out provisions do not apply. For purposes of this exemption, all depository financial institutions entities are regulated by the same regulator.14 The common brand must consist of more than just a shared name or logo. While no examples are provided, the limiting language is intended to prevent use of the exemption for cross-marketing diverse products that are similar in label only. But given the other requirements (affiliate relationship, line of business), it is not apparent what kind of products and services are intended to be excluded. employees or offices in California, were not licensed to do business in California, did not own California property, and did not advertise the product in question in California. In fact, it was the plaintiff who called the telemarketer, claiming that that the company initiated the “upsell” of an unwanted product while knowing she was a California resident. 11 Sections 4052.5 and 4053(a). 12 Section 4052(d). 13 Both the disclosing and receiving entity must be in the same line of business, and the only qualifying businesses are banking, insurance, and securities. Section 4053(c)(2). 14 Section 4053(c). For purposes of this exception only, as applied to supervised banks, an affiliate is defined as a whollyowned bank subsidiary (or chain of wholly-owned subsidiaries), or two banks wholly owned by the same bank or holding company. Note that this definition differs from the general definition in two important aspects. First, the subsidiary must be wholly owned and not simply controlled by the bank, and the affiliate and the bank must both be wholly owned by the parent. In contrast, GLB and the general rule under SB1 both refer to the more common definition of “control,” meaning 25% ownership or voting power. Credit unions under SB1 are deemed to control their credit union service organizations (CUSO’s) only if they are at least 67% owned. Second, when referring to regulated banks, the bill excludes the Federal Reserve among the list of banking regulators. But because the state Department of Financial Institutions jointly supervises state Federal Reserve member banks, this omission should not pose a problem with most banks. Note also that the definition of affiliate for purposes of this exemption does not explicitly include a parent holding company, but the omission may be of no consequence. If the holding company performs no services, then its exclusion does not matter. If the holding company engages in support services for its subsidiaries, then the holding company itself may be deemed a financial institution within the broad meaning of the Bank Holding Company Act (12 U.S.C. 1843(k), and thus be qualified to share information with its financial institution subsidiaries. The ability of the bank to share information with the parent under this exception, however, does not appear to be specifically permitted. SB1 includes an additional “exception” from the notice and opt-out requirement: information is not deemed to be disclosed “merely” because customer information is maintained in an information system that is used in common by affiliated entities, even though employees from the related entities have access. Similarly, a disclosure does not result merely from a consumer gaining access to a web site jointly operated or maintained under a common name of a bank and its affiliate. It is uncertain how broadly the joint web site exception will be construed. Use of the term “access” suggests the conveying of information in the form of an internet “cookie” or other information collecting device rather than, for example, information obtained in the course of applying for a product on line. As to the joint database exception, use of the term “merely” suggests that it is intended to preclude application of the notice and opt-out requirements if information is shared solely because a family of companies manages its customer data through a separate entity. As drafted, this exception should not be construed to apply if an affiliate uses the bank customer’s information to market its own products. The provision goes on to state that if a consumer “has exercised his or her right to prohibit disclosure pursuant to this division, nonpublic personal information [may not be] further disclosed or used by an affiliate except as permitted by this division.” This presupposes that a customer is given an opportunity to prohibit disclosure. Certainly, if a customer has opted out pursuant to a notice the bank was required to provide for other reasons, then the affiliate would not be permitted to make further use of the customer’s information.15 But even if a right to prohibit a disclosure is not required for other reasons, it would appear that the intent 15 On occasion, a bank will receive a request to opt-out of affiliate sharing in response to a GLBA notice (even though the opportunity to opt-out was not provided), but SB1 does not contemplate this situation because it refers to a consumer direction “pursuant to this division.” of this exception is to accommodate shared databases, and not to create a broad exception for marketing among affiliates. Credit card rules. The new law includes three special rules governing banks issuing credit cards that bear the name of a non-affiliated third party. But for these rules, a disclosure would otherwise be subject to optout or opt-in. Where a bank issues a “credit account” bearing the name of a retailer (or a name proprietary to a company primarily engaged in retail sales), the bank may provide the retailer with cardholder name and address information, and a record of the purchases made with the retailer. If the account can only be used for transactions with the retailer or its retail affiliates, then the bank may disclose any nonpublic personal information regarding the account in connection with offering or providing the retailer’s products or services. This provision is included in the definition of “necessary to effect, administer, or enforce,” which prefaces the general transactional and administrative exceptions.16 A different provision applies to what is called an “affinity” card program, where a bank issues credit cards bearing the name of an “organization or business entity that is not a financial institution” (referred to as an affinity partner, but excluding retailers17). A disclosure under this provision is subject to the notice and opt-out requirements. Pursuant to such a program, a bank may disclose the cardholder’s name, address, telephone number, email address, and a record of purchases made with the affinity partner.18 In connection with the issuance of any other financial product or service19 on behalf of an affinity partner, a bank may disclose the customer’s contact details only. Also, the disclosure may not be done in a way that reveals any additional customer information. The affinity partner must be contractually obligated to keep customer information confidential and to use the information only to verify membership, verify contact information, or offer the affinity partner’s own products or services. If the affinity partner sends an email message to the customer, the message must identify the sender and provide a cost-free means for the recipient to elect not to receive further email messages. Note that if the bank’s privacy notice includes an opt-out provision for non-affiliated third party sharing (pursuant to a joint marketing agreement), it may be prudent to include a separate opt-out notice for sharing with an affinity partner because a general opt-out would also be effective as to sharing with an affinity partner. As noted, a credit card issued in the name of another entity is treated differently under SB1 depending largely on whether the entity is a retailer, referred to as a company primarily engaged in retail sales. The distinction would be justified under the assumption that retail cards are only used for transactions made at the retailer, because the law should not interfere with a bank’s ability to service the retailer’s accounts. However, the “necessary to effect” provision clearly contemplates cards that can be used widely. Cards 16 Section 4052(h)(1)(C). Section 4054.6(e). 18 Section 4054.6. 19 Section 4054.6(b). 17 issued in the name of non-retailers, for example an airline, would fall under the more restrictive affinity card provision even though those cards may also be used widely. The final credit card provision, the broadest, is available for information sharing pursuant to servicing a “private label credit card program.” This exception applies to an “entity” with whom a financial institution operates a program, and is a blanket exception from SB1.20 None of the terms, “retailer,” “affinity,” and “private label” is defined. Thus, it is not entirely clear when an entity should be treated as a retailer (not subject to consumer election) or under the more restrictive affinity card provision (subject to opt-out and information limits). For example, is a “New York Yankees” card an affinity card or a retailer card (because the organization sells baseball merchandise)? The private label provision would appear to apply to financial institutions only, but this is only a reasonable inference, since the section refers to “another entity” rather than a financial institution. Joint marketing agreements A key issue that CBA has refused over the years to compromise on is that the bill must maintain equal treatment of affiliate sharing and sharing with non-affiliated joint marketing partners. The industry had fought for the same result in GLBA to ensure that smaller banks, which typically do not have affiliate relationships, are able to provide a broad array of financial products and services through marketing agreements with third party providers. The final version of SB1 makes what is known under GLBA as joint marketing agreements subject to optout rather than opt-in (that is, it is treated generally the same as affiliate sharing).21 Once again, only the disclosure of information to third parties for marketing purposes is subject to opt-out. Broad exemptions are available for disclosures for operational and administrative purposes. A bank may share customer information with a nonaffiliated financial institution pursuant to an agreement to offer financial products or services jointly. The agreement must require the receiving institution to maintain the confidentiality of the information and prohibit it from disclosing or using the information other than in the course of providing the jointly offered product or service. Agreements entered into prior to January 1, 2004 are not subject to the notice and opt-out requirement until January 1, 2005. Details of notice requirement SB1 does not distinguish between an initial and annual notice. Also, unlike GLBA, it does not provide guidance on the timing of providing a notice when a customer relationship is established,. The general rule is that information may not be shared until 45 days after an annual notice and opportunity to opt-out have been provided.22 Annual means at least once in any period of 12 consecutive months during which the customer relationship exists.23 20 Section 4056(b)(1). Section 4053(b)(2). 22 Section 4053(d)(3). 23 Section 4053(d)(5). 21 A form opt-out notice is provided that, if used, creates a conclusive presumption of compliance (see form attached to this Bulletin). Notices that are not in the form provided must be submitted to the state Office of Privacy Protection (OPP) within 30 days after its first use. A rebuttable presumption of compliance applies if a non-statutory form is submitted to the bank’s regulator for approval, and the approved form is filed with the OPP.24 A non-statutory notice must be no more than one page and meet all of the following requirements: Title and headers: the notice must use the title: “IMPORTANT PRIVACY CHOICES FOR CONSUMERS” and the headers (as applicable), “Restrict Information Sharing With Companies We Own Or Control (Affiliates)” and “Restrict Information Sharing With Other Companies We Do Business With To Provide Financial Products And Services.” • • • • • • Clear and conspicuous/format. The titles and headers must be clearly and conspicuously displayed, and no text in the notice may be smaller than 10-point type. The notice must have “wide margins” and “ample line spacing” and use boldface or italics for key words. Separate document. The notice must be provided as a separate document, meaning that it may not be incorporated into another document. Opt-out opportunity. The opportunity to opt-out must be “stated separately” (presumably meaning it cannot be imbedded in a paragraph) and may be exercised by checking a box. Prominence. The notice is “designed to call attention to [its] nature and significance.” Clarity. The notice uses clear and concise sentences, paragraphs, and sections; uses short explanatory sentences (an average of 15-20 words) or bullet lists, and avoids multiple negatives, legal terminology, and highly technical terminology, and explanations that are imprecise and readily subject to different interpretations. Flesch score. The notice must achieve a minimum “Flesch” reading ease score of 50, not including the required title and header(s). As defined in Title 10, Section 2689.4(a)(7) of the California Code of Regulations, the Flesch Reading Ease Score rates text on a 100-point scale, as follows: 206.835 - (1.015 x ASL) - (84.6 x ASW), where: ASL = average sentence length (the number of words divided by the number of sentences), and ASW = average number of syllables per word (the number of syllables divided by the number of words). The higher the score, the more readable is the text. The language used where the customer makes the election whether to opt-out may not score lower than the corresponding language used in the text of the notice describing the options. Examples may be provided as long as the clarity and readability standards are met. Delivering the notice. The SB1 opt-out notice may be delivered in a number of ways, though no specific mention of personal delivery, such as at the bank upon account opening, is made. It could be delivered by mail alone. If delivered with the GLBA notice, the envelope must either include only additional privacy information and nothing else, or the two notices may be part of an envelope containing a bill, statement of account, or application requested by the consumer. This option would appear to be the most feasible. If the SB1 notice is delivered with any other mailing, it must be the first page of the mailing, and the envelope 24 Section 4053(d)(2)(B). may not include the GLBA notice. Additionally, except where the SB1 notice is delivered with a bill, statement, or application, on the outside of the envelope must be clearly printed in 16-point boldface type: “IMPORTANT PRIVACY CHOICES.” A privacy notice may be delivered electronically if it complies with applicable provisions of the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (ESIGN Act), complies with the requirements applicable to paper notices (except providing a return envelope), and the notice is delivered in a form the consumer may keep. A consumer may reply electronically, and may not be required to reply in another manner. GLBA does not explicitly refer to the ESIGN Act, which sets forth detailed standards regarding consent, prior notice about the right to receive a paper record, the right to withdraw consent, and other requirements. Also, SB1 does not include the detailed guidance contained in GLBA regulations setting forth the conditions in which an initial notice and annual notice may be provided electronically. SB1 states that an electronic notice must be delivered, and that it is insufficient that it is only “made available” to the consumer. This would suggest that the notice may not be incorporated into an on-line application process by appearing on a web page or made available as a link, but must be delivered by email some time during or after the transaction. It also casts doubt on the ability to notify a customer by email of the availability of a new privacy notice that is posted on a web site. Opportunity to opt-out. A consumer must be given a reasonable opportunity after receiving a notice to optout, but no set period of time is provided. A consumer may opt-out at any time, and the bank must comply within 45 days after receipt of the consumer’s election. The election is in effect until otherwise stated by the consumer. A self-addressed return envelope must be included with the notice. If the bank has more than $25 million in assets, it must either provide a first class business reply return envelope or a self-addressed envelope along with two alternative cost-free means for opting out, such as use of a toll-free telephone number, a toll-free fax number, or an email address. General exceptions The general exemptions available in SB1 largely track those available under GLBA, and include new ones. Exemptions are available: • • • • • • • • • • • for transactional and servicing purposes in connection with securitizations and secondary market sales upon consumer consent or request to safeguarding information/protecting the bank relating to representatives of the consumer relating to rating agencies, auditors, etc. pursuant to the Right to Financial Privacy Act and other laws governing access by public entities in connection with sales and mergers to comply with legal process and other laws, including specifically the USA PATRIOT Act pursuant to the Fair Credit Reporting Act to report elder abuse • • • to identify or locate missing children, witnesses, criminals and fugitives, parties to lawsuits, parents delinquent in child support payments, organ and bone marrow donors, pension fund beneficiaries, and missing heirs. to complete a real estate appraisal relating to insurance and securities Other services. A new exception is available for a disclosure as necessary for an affiliate or a nonaffiliated third party to perform “business or professional services, such as printing, mailing services, data processing or analysis, or customer surveys, on behalf of the financial institution.” The conditions are that the services could lawfully be performed by the bank, a confidentiality agreement is in place limiting disclosure and use of the information, and the bank does not receive any compensation from the other entity in connection with the release of the information. Enforcement The state Attorney General and a financial institution’s functional regulator are exclusively granted authority to enforce SB1.25 A person who negligently discloses customer information, or intentionally obtains, discloses, or uses nonpublic personal information is liable for a civil penalty of $2500 irrespective of the amount of damages suffered by an affected consumer. A cap of $500,000 applies to a negligent disclosure of information of more than one individual, but there is no cap applicable to any intentional violation. If a violation results in the identity theft of a consumer, as defined by Section 530.5 of the Penal Code, the applicable penalties are doubled. Again, an action by a private party under B&P Section 17200 is not necessarily foreclosed. Other provisions Insurance. A general exception26 is available for a disclosure that is “required, or is a usual, appropriate, or acceptable method for insurance underwriting, or the placement of insurance products with insurance companies, at the request of the consumer, for reinsurance, stop loss insurance, or excess loss insurance purposes, or for any of the following purposes as they relate to a consumer's insurance: • • • • • • • account administration reporting, investigating, or preventing fraud or material misrepresentation processing premium payments processing insurance claims administering insurance benefits, including utilization review activities participating in research projects as otherwise required or specifically permitted by federal or state law The special rules governing wholly-owned affiliates marketing same-brand products also applies to insurance and management entities of a single insurance holding company system, where the system consists of one or more reciprocal insurance exchanges and has a single corporation or its wholly-owned subsidiaries providing management services to the exchanges.27 25 Section 4057. Section 4052(h)(3). 27 Section 4053(c). 26 Licensed insurance and securities professionals28 are permitted to share customer information with each other through a written agreement “relating to insurance or securities transactions” that includes restrictions on the use of customer information in a manner consistent with the contract and SB1, and an explicit provision that the transactions specified in the agreement fall within the scope of activities permitted by the licenses of the parties. SB1 does not limit the ability of insurance producers and brokers to respond to requests for price quotes as long as any disclosure of customer information is made in the ordinary course of business in order to obtain those quotes.29 A disclosure by an insurer or its affiliates to an exclusive agent (both employees and contractors) is permitted as long as the agent does not disclose customer information to any party except as permitted by SB1. The rules governing shared databases apply to disclosures between an insurer (or its affiliate) and its exclusive agents; that is, mere access to a shared information system is not a disclosure, and customer information is not shared if a consumer has prohibited it.30 Notice to same household/joint notice. As under GLBA, if joint accountholders reside at the same address, only one privacy notice is required.31 A notice may be delivered jointly with an affiliate or other financial institution as long as it accurately discloses the practices of the entities.32 Non-discrimination. A bank may not discriminate against or deny an otherwise qualified consumer a financial product or a financial service based on a consumer’s opt-out decision or decision not to opt-in. However, a bank is not liable if the inability to disclose information prevents the product or service from being provided. The bill does not prohibit the offer of incentives or discounts in exchange for a specific response to a notice.33 Third party receivers of information. Anyone who receives nonpublic personal information from a bank, whether an affiliate or non-affiliated third party, is under a legal obligation not to disclose the information to any other entity unless the disclosure would be lawful if made directly by the disclosing bank. An entity that receives nonpublic personal information pursuant to a general exception may not use or disclose the information except in the ordinary course of business to carry out the activity covered by the exception. A copy of SB1 may be obtained from the website: www.leginfo.ca.gov/bilinfo.html (type in “SB1” and choose chaptered version. SB1 is effective July 1, 2004. 28 These are persons holding a producer’s license, surplus lines license, life and disability analyst license, stated and federal investment advisors, and securities dealers licensed with the National Association of Securities Dealers. See Financial Code Section 4056.5. 29 Section 4056.5(b). 30 Section 4056.5(c). 31 Section 4054(b). 32 Section 4053(d)(7). 33 Section 4053(a)(1).