Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and

advertisement

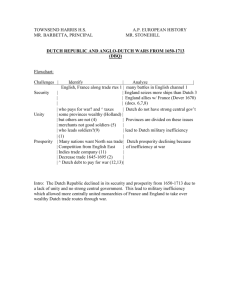

FWR_Boer.book Page 413 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation A classification model, an analysis of issues under current tax law and a proposal for changes in the application of the Dutch Personal and Corporate Income Tax to the Anglo-American trusts Introduction This research focuses on the application of the Dutch tax system for personal and corporate income tax purposes to the Anglo-American trust. Dutch civil law is based on the Roman law system and is unfamiliar with the concept of trust that has developed in the common law. The basic structure of a trust relationship is that property – ‘trust res’ – is placed under the control of a trustee who administers this property as a legal owner for one or more beneficiaries. The trust property has a separate position within the assets of the trustee. It is, for instance, not considered part of the trustee’s private assets in case of a bankruptcy. Although an Anglo-American trust has no legal personality, the separate position of the trust property within the trustee’s assets does lead to the view of isolated trust assets. Although the Anglo-American trust is not a natural element of the Dutch legal system, its concept increasingly presents itself within the Dutch legal sphere. This raises various tax law issues. Thus, the application of the rules of Dutch tax law to the ‘alien’ Anglo-American trust produces ambiguities on a number of fronts. The Dutch tax administration has always been reluctant towards the Anglo-American trust in practical situations, as it could lead to the creation of untaxed, not immediately allocable assets. First of all, embedding Anglo-American trusts within the Dutch tax system raises questions of how to qualify trust relationships for tax purposes. To do this, it needs to be determined whether for Dutch personal and corporate income tax purposes Anglo-American trusts are regarded as either non-transparent or transparent entities. Next, the rules of the Income Tax Act 2001 (hereinafter PITA 2001) and the Corporate Income Tax Act 1969 (hereinafter CITA 1969) must be applied to the Anglo-American trust and the legal relationships of the persons involved. Here, too, ambiguities can be acknowledged, as initially Dutch (tax) legislation failed to take sufficient account of special-purpose funds, such as the Anglo-American trust. The tax legislator wanted to ban both the ambiguities and the possibility of tax avoidance involving untaxed, not immediately allocable assets. On 1 January 2010, a legal framework for so-called separated private assets (hereinafter: separated private assets regime) was introduced. A notional allocation lies at the heart of the separated private assets regime. The separated assets are attributed to the contributor (normally – but not always – the settlor) during his life and thereafter to his heirs. The solution opted for with the separated private assets regime is in stark contrast with civil law reality. Neither does it align with the entity approach that the Dutch tax system seems to follow in respect of the Anglo-American trust. My research into the application of Dutch tax law to the AngloAmerican trust shows this to be a questionable solution. Therefore, I have researched whether the tax treatment of trusts based on an entity approach is better suited to the existing Dutch tax system. Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation 413 FWR_Boer.book Page 414 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM Research goal and research questions The central question of this research is: Considering the basic assumptions and criteria applied when distinguishing between transparent and non-transparent entities for tax purposes, how can the Dutch tax system be applied to the Anglo-American private express trust in a consistent manner? The research into the adoption of Anglo-American trusts is based on the existing Dutch tax system for personal and corporate income tax purposes – a system that distinguishes between the taxation affecting natural persons (personal income tax) and independent entities (corporate income tax). Two subquestions have been formulated to answer the central research question. Firstly, it will have to be determined which of the two taxes referred to above applies if assets have been transferred to a special-purpose fund like the Anglo-American trust. This first subquestion deals with how to determine the classification for tax purposes of the Anglo-American trust, based on the criteria applied when determining the independence of (foreign) legal forms in the Dutch tax system. The relevant criteria have been derived from the basic assumptions the legislator applied when designing the personal and corporate income tax system. Next, the criteria have been included in a test model for the classification of legal forms for tax purposes. Using this test model, the classification for tax purposes of both the fixed trust and the discretionary trust have been researched. It is concluded that within the Dutch tax system both types of trusts should be regarded as nontransparent entities. The outcome resulting from the classification model has then been compared with the views regarding the classification for tax purposes of Anglo-American trusts in case law and literature. Secondly, it has been researched what problems occur if the Dutch tax system is applied to the Anglo-American trust. Based on the classification for tax purposes of the AngloAmerican trust as an independent entity, the issues analysed regard those that occur in respect of the Anglo-American trust and the persons involved, if the provisions of the PITA 2001 and CITA 1969 are applied. These issues include: (i) cases of non-taxation and double taxation, (ii) inconsistencies in and the lack of legislative texts, and (iii) a different treatment of commercially comparable cases. The goal of the research is to arrive at a consistent system for the treatment of special-purpose funds in the Dutch tax system, using the Anglo-American trust as a benchmark. Not only can this eliminate the tax issues identified relating to Anglo-American trusts; a consistent treatment of Anglo-American trusts for tax purposes will also contribute to an accepted use of the trust as a legal concept in The Netherlands. The research will ultimately outline a proposal for the consistent treatment of the Anglo-American trust based on an entity approach. In the process of creating a proposal I will discuss and analyse the separated private assets regime, as this regime assumes a different attribution of assets/income to the persons involved in the trust. This regime, thus, follows a pattern fundamentally different from a proposal based on an entity approach. Finally, both alternatives for embedding the AngloAmerican trust are assessed according to a test framework that provides a concrete interpretation of the legal principles of legal equality, legal certainty and efficiency. Set-up of the research The research comprises three parts: Part I Part II Part III 414 The doctrine of the classification for tax purposes Civil law aspects of the Anglo-American trust Treatment of Anglo-American trusts in the Dutch tax system Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation FWR_Boer.book Page 415 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM A classification model is developed in part I (chapters 2 through 5), according to the basic assumptions of the Dutch legal concepts used in making the distinction between transparent and non-transparent entities. The classification model serves as an instrument for assessing the classification of the Anglo-American trust in the Dutch tax system (subquestion 1). Chapter 2 contains a description of how the Dutch tax system for personal and corporate income tax purposes has been set up. Chapter 3 analyses the theoretical background of the doctrine of classification for tax purposes. Next, chapter 4 refers to legislative history, case law and corporate income tax literature to distil the criteria for determining the classification of legal forms/arrangements for tax purposes as independent entities. This approach is referred to as the ‘corporate income tax dimension’ of the classification doctrine. Chapter 5 assesses when allocation of assets and income to an underlying subject is possible, if a legal form/arrangement alters the original relationship of the subject to the underlying object (i.e. assets and income). The question of whether it is possible to allocate income and assets to the underlying parties involved, is referred to as the ‘personal income tax dimension’ of the qualification issue. Part II (chapter 6) includes a discourse on Anglo-American civil trust law. This explanation is necessary for further researching the classification for tax purposes of the Anglo-American trust as a legal relationship and, accordingly, to develop a proposal for a consistent treatment of the Anglo-American trust in the Dutch tax system. Part III (chapters 7 through 9) researches – using the classification model developed – whether the Anglo-American trust should be approached as a (non-)transparent entity. To this end, chapter 7 first discusses the acknowledgement for tax purposes of a trust relationship. The central question in that chapter is how Dutch tax law takes account of the existence of an alien ‘legal concept’ like the Anglo-American trust. Chapter 8 comprises the test model based assessment of the classification for tax purposes of the Anglo-American trust. Next, its outcome is compared with the views from case law and literature. Chapter 9 researches the problems of the application of the PITA 2001 and CITA 1969 to the Anglo-American trust with the Dutch tax system. Following the wish to eliminate these bottlenecks determined within the existing tax system in a balanced manner, a proposal is prepared for a consistent tax treatment of the Anglo-American trust based on an entity approach. Next, an analysis is made of the separated private assets regime implemented on 1 January 2010 as an alternative to a solution based on an entity approach. Both alternatives have subsequently been compared according to a test framework that provides a concrete interpretation of the legal principles of legal equality, legal certainty and efficiency. Summary of the qualification model The Dutch tax system for personal and corporate income tax purposes has been set up as a subject-focused system. In other words, the nature of the subject is decisive for placing income in either the corporate or the personal income tax sphere. The subject not only acts as a taxable person, he is also an allocation centre for the assets and income to differentiate between the PITA 2001 and the CITA 1969. In comparison to the personal income tax, designation of taxable persons for corporate income tax purposes (‘entities’) is less unequivocal. In addition to legal persons, legal forms without legal personality, too, may be non-transparent (i.e. taxable) entities. As a result, a sharp division between the personal and corporate income tax sphere cannot be made in theory. However, the Dutch personal and corporate income tax system can be assumed to be a coherent system: any overlaps or blank spots are not intended. Designating a legal form as a non-transparent entity can be considered the heart of the classification doctrine. More specifically, the classification doctrine is derived from the Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation 415 FWR_Boer.book Page 416 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM concept of ‘legal intermediations’, according to which a legal form may cause an interruption on the line between subject and object. An interruption of the line between the original subject and the original object may indicate non-transparency, which can either be assessed by examining the interposed legal form (the corporate income tax dimension), or by analysing the entitlement of the subject to the original object (the personal income tax dimension). The Dutch tax law criteria for determining the (non-)transparency of a legal form, are derived on the basis of the goals the legislator had when setting up the tax system. Next, it is assessed how these criteria have evolved in policy decisions, case law and literature. In addition, based on the personal income tax dimension it is researched which entitlement of the subject to the object results in the income from the assets to be attributed to the former. The criteria in the income tax dimension are used in addition to the criteria in the corporate income tax dimension. This analysis has been used to set up a general test model for the classification of legal forms, including special-purpose funds. Test model for the qualification of legal forms (1) without a decision to distribute income, not one person will have obtained an entitlement to the underlying assets/income. When none of the persons involved in the legal form has any entitlement, the legal form can be regarded as non-transparent. If the underlying parties involved do have an entitlement, it will have to be assessed whether the results are for their account and risk. The results are not for the account and risk of the underlying parties involved, if the intermediation results in the following. (2a) The legal form itself holds the civil law title of the asset components, not the underlying entitled parties; and (2b) the underlying entitled parties are not liable beyond the amount of their contribution, due to the interposition of the legal form. The conditions reflect the idea of classic legal personality. The legal person holds the title in his own name – or at any rate, prevents the legal title to be in the name of the underlying parties – while causing limited liability at the same time. Legal persons are considered to be a non-transparent entity because of these characteristics. In this respect, the nature of a legal form as a ‘company with a capital dived into shares’ is of subordinate significance. Where the results are for the account and risk of the underlying entitled parties, the legal form is, in principle, transparent for tax purposes. If so, it still constitutes a non-transparency, if: (3) free accession and resignation is possible in respect of this legal form, within the meaning of art. 2, third paragraph, under c of the State Taxes Act [Algemene wet inzake rijksbelastingen]. In that case the legal form is considered to be an ‘open legal form’, which can be regarded as an independent entity. The relationship with the open legal form usually has the civil law characteristics of a share, or the entitlement can be put on a par with a share by way of legal assumption. 416 Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation FWR_Boer.book Page 417 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM If – based on its civil law characteristics – the Anglo-American trust is tested for the classification model, it can be determined that for application of the Dutch tax system, both the discretionary trust and the fixed trust form non-transparent entities. In respect of the discretionary trust this conclusion finds support in the case law and literature. As regards fixed trusts, too, it can be derived from case law that an entitlement has arisen in respect of the trust as a non-transparent entity. The literature sometimes shows different views. In respect of the revocable trust, which the settlor may revoke, the conclusion is that the possible revocation (i.e. the ‘power to revoke’) does not result in the trust being regarded as transparent. Case law, too, does not yet assume a revocable trust to be transparent for tax purposes. In contrast, the literature does note that the separated assets in a revocable trust must be deemed to continue to be part of the settlor’s assets. Issues regarding the application of Dutch tax law to Anglo-American trusts If the Dutch tax system is applied to the Anglo-American trust as an independent entity, various issues can be identified. They relate to both the Anglo-American trust as a subject for tax purposes and the persons involved. The following problems have been identified. Issues in respect of the Anglo-American trust in the CITA 1969 Domiciled tax residency – The special-purpose funds category (doelvermogens), which would include the AngloAmerican trust, is not listed as a domestic tax resident. As a result, Anglo-American trusts established in the Netherlands cannot be included in the CITA 1969, creating a taxation gap. – If domestic tax residency of trusts were to be assumed, it is ambiguous as to what should be included in the objective tax liability. Should, in that case, tax solely be levied if the Anglo-American trust carries on a business, or should investment income trigger taxation as well? Non-Dutch tax residence – As a result of the lack of domestic tax residency for special-purpose funds, the nondomiciled tax residency of Anglo-American trusts is not guaranteed, as this might trigger an unequal treatment of foreign trusts vis-à-vis Dutch trusts. – The object of taxation for non-domiciled tax resident Anglo-American trusts is formulated in considerably broader terms than the objective tax liability in domestic relationships for legal forms whose civil law structures most resemble special-purpose funds (Dutch foundations, or ‘stichtingen’). Again, there is unequal treatment between domestically established special-purpose funds and those established abroad. Issues in the PITA 2001 in respect of the persons involved in the trust Issues in respect of the settlor – If substantial interest shares are transferred to a trust by means of a declaration of trust it is unclear whether a (fictitious) sale can be assumed. In my opinion, however, art. 4.16, paragraph 1, under g, PITA 2001 should apply – although the text is not entirely unequivocal. – Where a substantial interest package is transferred to a trust, the existing legislative text of art. 4.22, paragraph 1, PITA 2001 (‘agreement’) insufficiently aligns with trust cases for the adjustment rule to be simply applied. As a result, it would be impossible to correct a transfer that is not effected at a commercial value. – It is ambiguous whether an entitlement to assets within the meaning of art. 5.3, paragraph 2, under f, PITA 2001 can be assumed in respect of a settlor who is involved in the trust management by the trustee. The supposed power of disposition of the settlor raises many discussions in case law. – If the power to revoke is regarded as a right of revocation, it is unclear what commercial value should be allocated to such power to revoke. Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation 417 FWR_Boer.book Page 418 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM Issues in respect of the trustee/protector – There are, effectively, no problems in respect of the trustee and protector. The trustee and protector have no economic interest in the trust property and solely receive a remuneration for their work, which can be taxed as profit from an enterprise or as labour income. Issues in respect of beneficiaries of a fixed trust (box 1) – It is unclear when an entitlement to distributions from a trust will lead to a periodic distribution (‘p.d.’; i.e. payments at a regular interval) in connection with the application of the transitional law (art. I, under O, Implementation Act PITA 2001). If the transitional law were applicable, the distribution would have to be taxed in box 1. – If a periodic distribution can be assumed, simply applying the transitional law does not seem to be possible. If read literally, the legislative text does not apply to the distributions from a trust (‘contribution’ and ‘agreement’). – The rationale of the regulation does not seem to concern the application of transitional law in respect of distributions from a trust. The offset method to be applied to periodic distributions is, after all, a calculation method. It does not actually reveal anything about the income character of the distributions. – Should the transitional law apply, it is difficult to determine the value of the initial performance. Hence, it is unclear which part of the distributions should be taxed in box 1. Issues in respect of beneficiaries of a fixed trust (box 2) – A beneficiary’s entitlement cannot be regarded as a share, as a result of which the substantial interest legislation does not apply to trust entitlements. – The definition of a ‘right of enjoyment’ in art. 4.3 PITA 2001 is ambiguous and it is difficult to apply in respect of a beneficiary’s rights. – The application to future interests is difficult within the set-up of the substantial interest regime. Issues in respect of beneficiaries of a fixed trust (box 3) – It is usually difficult to classify the sui generis rights that beneficiaries can derive from a fixed trust. As a result, where it concerns the valuation of trust entitlements in box 3, it cannot be determined whether the valuation rules must be applied in respect of (i) a right to a p.d., (ii) a right of enjoyment, or (iii) another property entitlement. – Where it is certain that the valuation must take place at the commercial value ex art. 5.19, paragraph 1 and paragraph 2, PITA 2001, ambiguity may arise regarding any value that can be allocated to formal powers. This may lead to discussions about the valuation of trust entitlements. – The valuation of trust entitlements can be highly complex, partly due to the conditions under which a sui generis right has been granted. If so, auxiliary methods such as the infringement rule will need to be called upon to determine the value. Issues in respect of beneficiaries of a discretionary trust (box 1) – If a p.d. derives from a discretionary trust, art. 3.101, paragraph 1, under d, PITA 2001 cannot be applied, because a discretionary trust has no legal personality. However, considering its background this provision does seem to be intended for distributions from special-purpose funds. Issues in respect of beneficiaries of a discretionary trust (box 3) – Theoretically, the lack of a ‘channel’ leading towards the discretionary trusts is not in itself a bottleneck. Due to the lack of an entitlement the beneficiaries cannot be included in the taxation. The assets transferred to the discretionary trust are, therefore, not (indirectly) liable for taxes in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, in these cases the legislator refers to untaxed, not immediately allocable assets – a situation he deems to be undesirable. 418 Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation FWR_Boer.book Page 419 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM – Effectively, the main bottleneck regarding the discretionary trust is the burden of proof: the question whether, notwithstanding the legal presentation, a beneficiary can derive an enforceable property entitlement from the trust relationship. As a result, this raises many discussions in case law. The issues referred to have three causes. Firstly, the wording of the legislative texts takes insufficient account of the specific civil law structure of Anglo-American trusts. Secondly, problems arise within the Dutch tax system due to the lack of a ‘channel’ between the Anglo-American trust and the persons involved. Since the Anglo-American trust itself is not included in the (Dutch) taxation, the separated assets cannot be included in the corporate income tax either. Thirdly, the assessment of the sui generis rights can lead to problems. Both the assessment of the entitlement’s nature and the determination of the entitlement’s value are difficult. Proposal for the application of the Dutch tax system to the Anglo-American trusts Proposal based on an entity approach The Dutch tax system regards the Anglo-American trust as a non-transparent entity. Based on this entity approach it has been researched what alternatives exist to eliminate the problems identified in respect of the Anglo-American trust in a balanced manner. Three different proposals for a consistent tax treatment of the Anglo-American trust have been outlined and assessed. Firstly, the alternative of the Anglo-American trust as an independent special-purpose fund in the CITA 1969 has been researched. Next, it has been examined whether the trust can be included in the scope of the PITA 2001. Thirdly, an entirely autonomous regime for special-purpose funds is discussed. Next, it has been concluded that the consequence of an entity approach in respect of the Anglo-American trust was that notional residences must be construed to extend the Dutch tax jurisdiction. After all, the trust’s effective management is generally situated abroad, which requires notional residences to create a Dutch tax jurisdiction. A number of criteria for a notional residences has been proposed based on foreign equivalents and proposals in literature. A link has been established with the contributor’s residence during his life. After his death, the special-purpose fund is deemed to remain established in the Netherlands for thirty years. Furthermore, I have proposed a generic safety net provision that aligns with the residence of the heirs/potential beneficiaries. Ultimately, a proposal has been prepared based on an entity approach that combines the three alternatives discussed earlier. The proposed regime is based on an autonomous regime for special-purpose funds within the CITA 1969. In this regime the object of taxation is determined pursuant to the PITA 2001. The advantage of this approach is the elimination of all the main issues, because tax is levied at the level of the entity. Hence, the tax liability is indirectly charged to the beneficiaries that eventually obtain a distribution. The merit of this proposal is not only that it is linked to the classification given to the Anglo-American trust within the Dutch tax system. It likewise achieves an equal treatment of separated and non-separated assets. The disadvantage is, however, that it requires (more) complex legislation and recourse must be taken to different notional residences. The separated private assets regime The separated private assets regime was introduced on 1 January 2010, to remove problems relating to the existence of untaxed, not immediately allocable assets. The methodology of the separated private assets regime is based on a different allocation of the trust assets. Contrary to the classification rules of the Dutch tax system for personal and corporate income tax purposes, separated private funds are ignored as an entity and are not regarded as an allocation centre in respect of the assets transferred into trust and the resulting income. Instead, the trust assets and the resulting income are attributed to the Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation 419 FWR_Boer.book Page 420 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM contributor during his life. With this, the separated private assets regime fully disregards civil law reality and brings about a taxation resulting in persons being taxed for income and assets they do not – and maybe never will – possess. The separated private assets regime has been analysed using the purposes of the legislator. The goal to counter untaxed, not immediately allocable assets has been achieved through the so-called notional allocation. However, the objective to treat separated and non-separated assets equally as much as possible has not been achieved, primarily because notional allocation does not apply if the separated private assets are subject to reasonable taxation. In that case, the separated private assets are regarded as an entity and substantial differences arise compared to non-separated assets. The analysis of the separated private assets regime leads to the following conclusions relating to the PITA 2001 and the CITA 1969: PITA 2001 – Due to the notional allocation, the existence of the Anglo-American trust is effectively ignored. – The notional allocation of art. 2.14 a PITA 2001 leads to extension of the Dutch tax jurisdiction. – The allocation of the separated assets to the grantor and his heirs is without further justification and is contrary to the ability-to-pay principle. – The wording of the provisions contains vague concepts that are not conducive to legal certainty. – The distinction between taxable and non-taxable separated private assets results in a ‘dual approach’, causing unequal treatment of separated and non-separated assets due to the non-allocation to contributor/heirs if reasonable tax is levied on the level of the separated private fund itself, resulting in unequal treatment of separated and nonseparated assets. – The application of the separated private assets regime to fixed trusts shows several ambiguities. – The allocation to the contributor/heirs cannot be put on a par with tax transparency of the trust and, hence, the non-transparency of the trust as an entity leads to several complications within the separated private assets regime. – The problems relating to the substantive assessment of the sui generis right of beneficiaries have not been removed. CITA 1969 – Application of the CITA 1969 continues to be based on the non-transparency for tax purposes of and the allocation to the separated private assets. – The effect of the separated private assets regime on the CITA 1969 is very limited in terms of non-taxable separated private assets. – Unequal treatment of separated and non-separated assets may present itself in respect of the taxable separated private assets as a result of the different tax bases in the PITA 2001 and the CITA 1969 and due to the lack of a ‘channel’ in respect of the persons involved in the separated private assets. Review of proposals for the application of Dutch tax law to Anglo-American trusts and recommendations The proposal based on an entity approach and the separated private assets regime have been compared using the assessment framework based on the principles of legal equality, legal certainty and efficiency. These principles have been operationalized for the purpose of this research. The following conclusions have been drawn from this review. The application of the Dutch tax system to Anglo-American trusts, based on an entity approach, in which the tax base of the special purpose fund is established pursuant to the provisions of the Personal Income Tax Act 2001, may produce the best alignment of the 420 Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation FWR_Boer.book Page 421 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM tax treatment of separated private assets and non-separated private assets. Although the separated private assets regime aims at this equal treatment, too, in several cases this is not achieved. Adoption of the trust under the entity approach has the major advantage that the tax due by the Anglo-American trust is effectively charged to the ultimate beneficiaries. This is a marked improvement on the separated private assets regime, for which a different approach has been chosen, i.e., allocation to the contributor during his life and thereafter to his heirs. This regime thus has the major disadvantage that it completely abstracts from civil law as well as economic reality, which causes legal inequality. Those who have to pay the tax do not possess the assets on which the assessment is levied. Abstraction from civil law reality within the separated private assets regime at the same time presents some major benefits. It enables the legislator to robustly solve the issue of the ‘untaxed, not immediately allocable assets’ using relatively simple legislation. However, this solution originated from ignoring the issue, accepting a substantial degree of overkill. After all, the Anglo-American trust still exists from a civil law perspective and, thus, tax will continue to be levied at the wrong level while recourse will regularly have to be taken to the special purpose fund for collecting the tax. In essence, the same result could be achieved under an entity approach respecting the civil law characteristics of the trust. This underlines the appropriateness of that solution. The separated private assets regime includes many open norms and poorly delineated concepts that lead to legal uncertainty. Their use is in part unavoidable and will also be required when applying an entity approach. Yet it can be concluded that by so doing, the legislator has in many cases shifted the burden of proof to the taxpayer. Moreover, it can be stated that attribution within the separated private assets regime cannot be put on a par with tax transparency. The assets and income are attributed as such to the contributor/heirs. The beneficiaries, on the other hand, retain a legally enforceable right vis-à-vis the trust(ee). As a result, there is no tax transparency towards the beneficiary: the nature, size and the moment when the assets/income become subject to tax may deviate from those of the original income. In that respect, the essential non-transparency of the Anglo-American trust is still manifest. However, tax treatment of the trust under the entity approach – as I have proposed – also presents some drawbacks. The major disadvantages of applying an entity approach are: (i) more detailed legislation is required and (ii) the power to tax is to be established based on the notional residences. Also political choices will have to be made in terms of the rates and credits applicable to private special purpose funds. Although the necessity of more detailed legislation implies a deterioration in terms of simplicity and efficiency, it could produce an improvement on the current separated private assets regime. As regards the notional residency – which are used in other countries, too – it can be observed that these should be formulated in even broader terms, if required, to express the nexus with the Dutch tax jurisdiction. If foreign taxation is avoided and foreign assets are kept out of the tax base, there will be a well-balanced system. Moreover, the Netherlands should make a reservation to art. 4, paragraph 1 of the OECD Model Tax Convention in respect of private special purpose funds. The above considerations justify the conclusion that the tax treatment of the trust based on an entity approach best aligns with the Dutch personal and corporate income tax system. The tax base should be determined in accordance with the PITA 2001. In addition, Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation 421 FWR_Boer.book Page 422 Wednesday, April 13, 2011 10:21 AM to create a coherent solution for all relevant taxes involved, a separate system could also be developed for the Dutch Inheritance Tax Act 1956. As it is unlikely that the separated private assets regime implemented on 1 January 2010 will be replaced shortly by a levy based on an entity approach, I have done some proposals that could be considered an improvement of the existing separated private assets regime. In this respect I have considered the Dutch Inheritance Tax Act 1956 as well. The most important recommendations are listed below. Recommendations for improving the separated private assets regime With respect to the PITA 2001 and the CITA 1969 1. The tax due as established under the separated private assets regime should first be collected from the special purpose fund. To do so, the tax assessment levied in respect of the contributor/heirs under the separated private assets regime should be in the name of the trust(ee). 2. For inheritance tax purposes, a reimbursement regulation may be developed to provide for those cases where the value of the actual acquisition by the heirs was nil or lower than that for which they were taxed. 3. The consequences of the lack of tax transparency within the separated private assets regime should be clarified in a Decree, particularly addressing the position of the fixed trust. 4. Evidence rules should be drawn up for determining the nature and size of the sui generis rights of beneficiaries. 5. The catchall ‘special purpose funds’ category should be included in Article 2 CITA 1969 for resident tax liability. 6. The separated private assets regime should fully be integrated in the CITA 1969, taking account of the difference between ‘tax transparency’ and ‘allocation’. 7. The regulation applicable to the ‘reasonable taxation’ of separated private assets should be replaced by a system under which a full credit for foreign taxes is granted. With respect to the Inheritance Tax Act 1956 8. The tax due should be collected first from the separated private fund. To do so, the tax assessment levied in respect of the heirs under the separated private assets regime should be in the name of the trust(ee). 8. The inheritance tax assessments could be replaced by protective tax assessments, with interest-bearing extension of the payment date being granted subject to collateral. 10. For inheritance tax purposes, a reimbursement regulation may be developed to provide for those cases where no or a lower acquisition took place at the level of the heirs. 11. Upon the contributor’s decease, a taxed acquisition by the special-purpose fund can be assumed at the rate applicable to non-relatives. The tax due could in that case be collected from the separated private fund without taxing the heirs first. 12. Then a complementary periodic levy can be designed – based on foreign examples – to the debit of the special purpose fund to recover any unpaid inheritance tax. Finally, the more general conclusion has been drawn that the introduction of the separated private assets regime warrants re-examining the possibilities under civil law for introducing a ‘Dutch family trust’ (familiestichting). If the separated private assets regime is improved as proposed above and a balanced system for introducing special purpose funds is realised, tax law should no longer be seen as an obstacle to the introduction of such a Dutch family trust. 422 Summary - The Anglo-American trust in Dutch personal and corporate income taxation