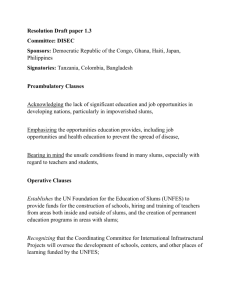

1 Housing and basic infrastructure services for all: A conceptual

advertisement