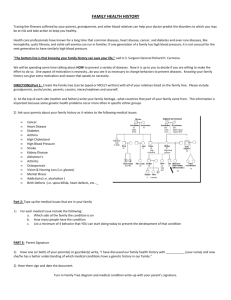

Introduction: living extended family lives

advertisement