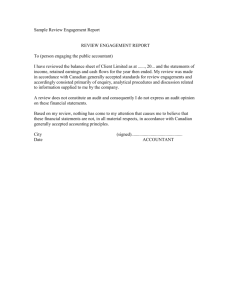

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

advertisement