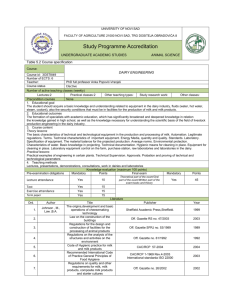

Milk Market Channel Structure: Its Impact on Farmers and

advertisement