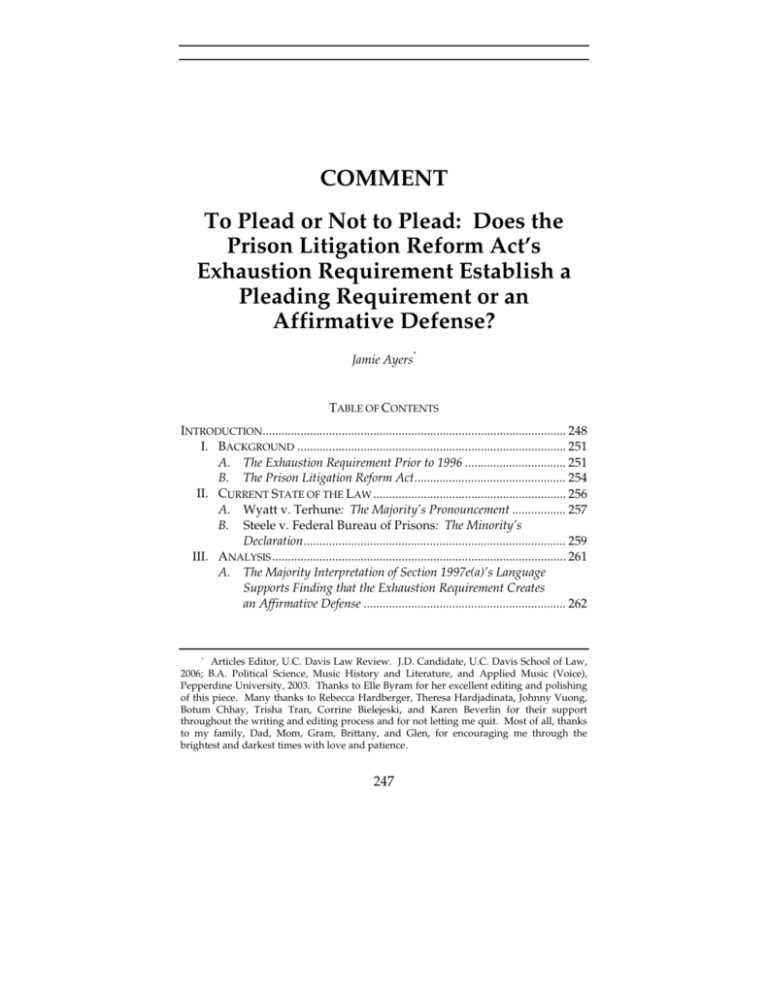

To Plead or Not to Plead: Does the Prison Litigation Reform Act's

advertisement