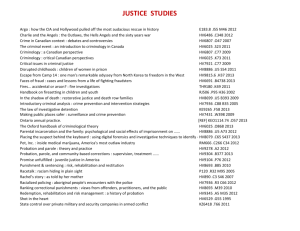

Drugs misuse and the criminal justice system: a review of the

advertisement