OCS Study BOEM 2014-611

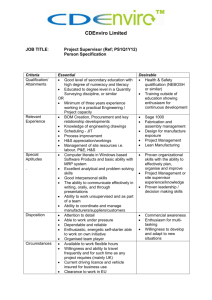

advertisement