America's Maritime Industry: The Foundation of American Seapower

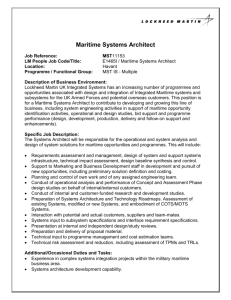

advertisement

Copy to come copy to come copy to come copy to come America’s Maritime Industry America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. A Report by the Navy League of the United States 1 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Contents The Foundation of American Seapower: Summary...........................................3 America’s Maritime Heritage..................................................................................5 U.S. Maritime Policy.................................................................................................6 America’s Maritime Industry Today.......................................................................7 Innovation in America’s Maritime Industry.........................................................9 Productivity.............................................................................................................10 Environmentally Friendly Mode of Transportation.........................................11 Economic Contribution: International Trade....................................................12 Domestic Economic Contribution......................................................................14 Supporting Our National Defense......................................................................16 Defense Industrial Base: Shipbuilding...............................................................18 Defense Industrial Base: Seafarers & Shipyard Labor......................................19 Homeland Security.................................................................................................20 The Past As Prologue.............................................................................................21 2 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Summary Maritime Americans From amidst the smoke, flames, and debris from the collapsed World Trade Center towers, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers and persons from neighboring boroughs and states made their way toward Battery Park at the southern end of Manhattan to try to escape the chaos that reigned about them. The bridges and tunnels were closed, the subways shut down. Manhattan was once again an island as it had been over a hundred years earlier, and they were trapped on that island. The only escape was by water. No one was in command. There was no single plan. (The New York City Emergency Response Center was buried in the rubble of the towers.) But on the surrounding waters, American mariners of every description saw the disaster unfolding and knew, without being told, what they needed to do. From throughout the harbor and surrounding areas a virtual armada of tugs, ferries, dinner and pleasure cruise boats, working craft of every description, and virtually every other craft available in New York harbor steamed toward the docks and seawalls of lower Manhattan to evacuate hundreds of thousands of fellow Americans. By nightfall, almost half a million persons had been evacuated by New York mariners who knew what they had to do and worked together to do it. It was one of the largest maritime evacuations in history. In that one afternoon and evening, Maritime Americans evacuated more people from Manhattan than were rescued during the famed Dunkirk evacuation early in World War II. No industry has been more vital to the success of our country than that of America’s maritime industry. The industry provides jobs for hundreds of thousands of Maritime Americans in every corner of our nation—from longshoremen in ports along our four seacoasts, to towboat operators navigating the Mississippi, to shipbuilders in East Coast dry docks, to the men and women who crew American-flag vessels of all types. The American maritime industry moves cargo and troops around the world in far greater volume, with far greater efficiency, than any other transportation mode. As a first line of defense, it also proud helps ensure greater homeland security. 3 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Summary The maritime industry transports commercial goods more cost effectively than trucks and rails — while providing the most environmentally sound mode of transportation. The industry’s humanitarian role is one that paints a positive picture of America worldwide, as it distributes food to the world’s poor and responds to global emergencies. And the industry stands as a primary driver of trade in one of the world’s largest economies. As detailed in this report, waterborne transportation provided by Maritime Americans is the lifeblood of much of the nation’s domestic commerce and international trade. With a heritage reaching back to the earliest days of this nation’s history, this report finds that America’s maritime industry today — • Is unique among the maritime nations of the world in its scope, magnitude, and diversity; • Is characterized by its innovation and productivity, and as being the most environmentally friendly mode of transportation; • Plays a vital role in ensuring this nation’s economic well-being and the growth of our economy both through international trade and its own role in our domestic economy; • Is essential to our national defense in deploying and sustaining American forces worldwide in support of our national interests and in the maintenance of the U.S. maritime industrial base; • Helps ensure our homeland security; and • Is poised and ready to help this country meet the transportation challenges of the 21st Century. 4 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. America’s Maritime Heritage Beyond its historical role in the founding of our nation, the American maritime narrative The United States is unique and extraordinary. The maritime grew up on the water industry in America directly or indirectly and remains a maritime provides or supports hundreds of thousands nation to this day. of jobs in every corner of our nation; helps Smithsonian National Museum ensure greater homeland security; moves of American History, “On the Water” cargo to war zones in far greater volume than (Online Gallery) any other transportation mode; transports goods far more cost effectively than any other mode; is the most environmentally sound mode of transportation; plays a humanitarian function in distributing food to the poor and responding to global emergencies; and stands as a primary driver of trade in one of the world’s largest economies. 5 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. U.S. Maritime Policy Following America’s independence, among the first acts of the new Congress in 1789 was an Act to encourage the use of American vessels for trading between the States, followed shortly by the Navigation Act of 1807. Over the ensuing years the United States adopted the principles that have guided our maritime industry into the 21st Century — • Reserve domestic commerce to vessels built, owned, and crewed by American citizens as a vital part of our national domestic transportation system and our national and economic security; • Maintain a shipbuilding and repair industrial base sufficient to provide modern vessels for the domestic fleet and new construction and repair capabilities for modern naval vessels in peace and war; and • Ensure a modern commercial fleet operating in the foreign trades capable of meeting national defense shipping requirements and to maintain a presence in international commercial shipping. There are four major legislative and interdependent struts supporting the U.S.-flag maritime industry: 1. The Jones Act requires that trade between two or more contiguous American ports must be conducted by U.S.- owned carrier companies who employ U.S. mariners aboard U.S.-built vessels. The Jones Act keeps American shipping companies, shipyards, mariners, maritime academies and thousands of Maritime Americans working. 2. Maritime Security Program (MSP) is a $186 million program that provides expense offset to a 60-vessel commercial fleet of container ships, roll-on, roll-off vessels and tankers that carry military cargo to and from the war theaters. This fleet has carried more than 70% of the cargoes supporting U.S. troops and Coalition forces in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2005. 3.Cargo Preference Laws require that a percentage of government cargo must be carried on U.S.-flag vessels. This cargo includes a wide range of home-grown or home-manufactured products from humanitarian aid to large construction machinery all over the world and is the lifeblood of the U.S.-flag fleet. 4. The Tonnage Tax is a tax regime passed by Congress in 2004 intended to level the playing field for U.S.-flag operators competing in foreign trades. Together, these government programs assure continuing investment in the U.S.-flag and guarantee that commercial sealift capability will be robust, efficient and affordable for national, economic, and homeland security. 6 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. America’s Maritime Industry Today The American Maritime Industry today is unique among the maritime nations of the world in its scope, magnitude, and diversity. Consider that the industry includes over 40,000 vessels that when connected with U.S. trucks and railroads gives the United States a strong domestic transportation system serving as a facilitator for international trade. • Modern, oceangoing ships, through ties to international carriers, link the U.S. economy to the global economy, maintain a U.S. presence in international trade, transport humanitarian aid to those in need, and support U.S. military forces worldwide; • Passenger vessels ranging from ferries in daily commuter services to cruise ships which together annually carry tens of millions of Americans to work and on vacation; • Thousands of towboats and barges operating on the Mississippi and Ohio River systems that play an essential role in transporting agricultural products from the American Midwest to ports for export; • Ships and barges of all descriptions operating in coastwise trade transporting bulk commodities along our coasts and between the continental U.S. and Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico; • Great Lakes vessels moving bulk commodities three times more efficiently than rail and 10 times more efficiently than trucks, which are the lifeblood of the U.S. steel industry in the region and that give industries in the region a competitive edge; 1 7 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. • Ports in every state ranging from those among the world’s largest that provides the gateways to the global economy through which flow U.S. imports and exports, and smaller regional ports which serve as hubs for domestic waterborne commerce; Tugs and related vessels of every description providing towing and • Tugs and related vessels of every description harbor services in every port in the nation; providing towing and harbor services in every port in the nation; Vessels providing offshore support to the oil industry in the U.S. Gulf • Vessels providing offshore support to the oil industry and off our coasts, ranging from exploration and drilling, support for oil in the U.S. Gulf and off our coasts, ranging from production facilities, and transportation of supplies, personnel, and exploration and drilling, support for oil production crude oil to U.S. coasts; facilities, and transportation of supplies, personnel, and crude oil to U.S. coasts; • A diverse dredging industry which not only helps to maintain and improve U.S. ports and waterways and helps replenish U.S. beaches from erosion, and which also provides services worldwide; and • A shipbuilding and repair industry ranging from shipyards building and maintaining the largest and best naval vessels in the world to medium and smaller yards which build and maintain the over 40,000 vessels comprising the domestic fleet. 8 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Innovation in America’s Maritime Industry Throughout its history, the American Maritime Industry has been characterized by its innovation and its productivity. Possibly foremost among the many innovations flowing from the American Maritime Industry has been the introduction of containerization. The idea of using some type of shipping container was not completely novel. Boxes similar to modern containers had been used for combined rail- and horse-drawn transport in England as early as 1792. The U.S. government used small standardsized containers during the Second World War, which proved a means of quickly and efficiently unloading and distributing supplies. However, in 1955, Malcom P. McLean, a trucking entrepreneur from North Carolina, bought a steamship company with the idea of transporting entire truck trailers with their cargo still inside. He realized it would be much simpler and quicker to have one container that could be lifted from a vehicle directly on to a ship without first having to unload its contents. This simplified the whole logistical process and, eventually, implementing this idea led to a revolution in cargo transportation and international trade over the next 50 years. His ideas were based on the theory that efficiency could be vastly improved through a system of “intermodalism,” in which the same container, with the same cargo, can be transported with minimum interruption via different transport modes during its journey. Containers could be moved seamlessly between ships, trucks, and trains. Almost from the first voyage, use of this method of transport for goods grew steadily and in just five decades, containerships would carry about 60% of the value of goods shipped via sea. It is certainly no exaggeration that the container revolutionized ocean freight transportation and made possible the global economy. In 2011, the Port of Los Angeles set a record by shipping over 2 million export containers alone, the first U.S. port to do so, and with its neighboring Port of Long Beach handled over 14 million containers in international and domestic commerce. Today containerization also plays a role in the shipment of supplies and equipment to U.S. military forces worldwide. Since 2009, 60% of the cargoes moving to U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan have been containerized, and U.S.-flag containerships have transported 75% of all equipment and supplies shipped to those countries. 9 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. The introduction of River Flotilla towing systems made possible barge tows of from 35-55 barges. The tow shown has the cargo carrying capacity of a 27,000-dwt freighter. The introduction of the 1,000-ft long self-unloading bulk ship on the Great Lakes increased vessel productivity by a factor of four. Self-unloading eliminated the need for costly and time-consuming cargo discharge and specialized onshore terminals. Virtually any level land within reach of the cargo boom became a potential terminal. Productivity Such innovation has enabled the maritime industry in America to be among the country’s most productive. For example, during the period 1965-95 the maritime industry outperformed American businesses generally based on average annual rate of productivity gain. A key factor in achieving these productivity increases has been increased vessel and crewmember productivity resulting from the introduction of containerization in the U.S.-flag offshore and foreign trades. As illustrated below, a modern containership has four times the annual cargo delivery capability as a first generation containership, resulting both in increased vessel productivity and productivity per individual crew member. If the same comparison is made to a post-WW II general cargo ship, the productivity increase would be approximately 16 times greater. 10 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Environmentally Friendly Mode of Transportation Marine transportation is widely recognized as the most environmentally friendly compared to other modes of freight transportation. In terms of fuel efficiency, for example, waterborne barge transportation is 39% more fuel efficient than rail and 370% more efficient than trucks. 2 The same holds true in terms of emissions. Based on ton miles traveled per ton of greenhouse gases (GHG) released, water transportation is similarly 39% less damaging to the atmosphere than rail and 370% less damaging than trucks. The maritime industry is also continually seeking ways to further reduce its environmental impact. Industry initiatives to help protect our marine and ocean environments include the introduction of low-sulfur fuels, shutting down main engines in part to reduce emissions, and working with government officials to establish best navigation routes to minimize environmental impact. Ton Miles Per Gallon of Fuel 800 576 600 400 200 413 155 0 Truck 11 Rail Inland Towing America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Economic Contribution: International Trade The Maritime Industry in America contributes to our national economy and economic wellbeing both through international trade — approximately 28% of our economy depends on imports or exports— and by virtue of the millions of jobs it creates or sustains domestically both within the industry itself and through its total value contribution to the economy. International trade is a critical component of the U.S. economy. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the trade-to-GDP ratio for the U.S. increased from about 20.5% in 1990 to over 28% in 2006. The World Bank predicts that this ratio will rise to 35% by 2020, showing that trade will become an even more important component of the U.S. economy. Trade will not only grow in absolute terms, it will also increase as a share of GDP and thus as a contributor to growth in U.S. jobs and wealth. If current trends continue, imports and exports will comprise almost 55% of GDP by 2038. In other words, trade will grow twice as fast as the U.S. economy as a whole.3 12 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. With 95% of our foreign trade moving by ship, the role of maritime transportation will continue to increase. In 2009, for example, 6,996 oceangoing vessels made 55,560 calls at U.S. ports transporting 1.2 billion metric tons of U.S. imports and exports with a combined value in excess of 1 trillion U.S. dollars. On average, that equates to over 180 oceangoing vessels calling at U.S. ports every day. 4 Maritime Share of U.S. Trade Millions of Metric Tons It is projected that the maritime share of U.S. trade as measured by TEU’s (20-foot Container Equivalent Units) will double by 2023 to about 45 million TEU’s and increase to 75 million TEU’s (about 2.4 billion tons) by 2038. Trade by sea will grow even faster by value, rising from about $1.8 trillion in 2008 and to about $10.5 trillion in 2038. Thus, over the next 30 years, trade will increase by an average annual growth rate of 1.9% by volume and 6.4% by nominal value. These growth rates reveal that the U.S. will be trading in goods of higher value per ton and highlight yet again the increasing importance of maritime trade to the U.S. economy and national wealth creation. 5 Overall, when trade-dependent jobs are included in the analysis, it is estimated that maritime industry related employment represents approximately 13 million U.S. jobs.6 13 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Domestic Economic Contribution The maritime industry is not just about the shipment of goods or transporting passengers. Beginning with the shipyards that build and repair the vessels operating in our domestic transportation system, the industry provides or supports jobs throughout the economy. The maritime industry annually accounts for: • 2.56 billion short tons of cargo, 40% of which is domestic • 100 million passengers on ferries and excursion boats • 100,000 shipyard jobs for skilled craftsmen • 2.5 million domestic jobs indirectly created by shipyards • $29 billion in wages • $11 billion in taxes • $100 billion in annual economic output In the Great Lakes region, economic data shows that more than 1.5 million jobs in the eight states bordering on the Lakes are directly connected to waterborne trade, generating $62 billion in wages in that region alone. 7 Other studies by maritime industry related trade associations estimate that the industry itself employs 1.6 million Americans overall in water transportation and related sectors including port services and drayage and shipbuilding and repair. 8 14 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. This would equate to more than $105 billion in direct economic output to the U.S. economy, in addition to the maritime industry’s role as a key enabler and component of the approximately $3 trillion in economic output of American importers and exporters. Waterborne shipping is an extremely cost effective mode of moving cargo in the domestic economy compared to other modes. In 2001, average freight revenue per ton-mile for barges was less than half the next cheapest alternative (oil pipelines), less than one-third that of Class I railroads, and less than 3% of the cost of shipping by truck. Historically the cost of shipping by water for domestic cargoes has been going down, not up. While the Consumer Price Index increased by 34% over the period 1990-2001, revenues per ton mile for barge commerce declined by 5% in nominal terms, a real reduction in charges to barge customers—including farmers in the Middle West and Plains States— of 29%. In contrast, over the same period the cost of shipping by truck increased by 9%.9 The economic contributions of the American Maritime Industry to the domestic economy go beyond direct payments and providing transportation. Shipbuilders purchase steel and other products from domestic companies to build and repair ships. Marine suppliers of all types sell products and services to the industry, with added employment and tax revenue benefits. 15 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Supporting Our National Defense Since the earliest days of our history, the American Maritime Industry and Merchant Marine have played vital roles in our national defense. Through two World Wars and numerous conflicts before and since, American merchant ships and their civilian mariner crews have deployed and sustained American Armed Forces truly serving as the Fourth Arm of our National Defense. “We simply cannot, as a nation, fight the fight without the partnership of the commercial maritime industry.” General John W. Handy, USAF, Commander, U.S. Transportation Command, Before House Armed Services Committee (2002) The Maritime industry’s contributions to national defense go beyond the vital role of deploying and sustaining our troops, for without its contribution to the maritime sector of our national defense industrial base, the United States would not be the seapower it has been since the Second World War and must continue to be in the future. The United States-flag commercial shipping industry provides the U.S. military with a highly effective partner in the provision of military sealift services around the globe by delivering cost-effective service at a high level of performance quality and dependability. Through the Maritime Security Program (MSP) and Voluntary Intermodal Sealift Agreement (VISA), the U.S.-flag commercial fleet provides vessels, crews, and worldwide intermodal facilities for defense use— wherever and whenever needed. Foundation for National Security Sealift The Maritime Security Fleet (MSF), MSP and VISA programs serve as the foundation for U.S. national security sealift by— • Maximizing the capability, readiness and reliability of U.S. strategic sealift through immediate assured access to intermodal capacity under contingency contracts with each of the individual operators; • Permitting immediate expansion of sealift capacity in an emergency as well as a capacity reserve (“insurance”) consisting of un-tapped U.S.-flag capacity and the foreign-flag capacity of VISA participants committed under VISA; 16 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. • Ensuring the availability of trained, STCW (Standards of Training Certification and Watchkeeping) certified mariners to crew U.S. Government organic sealift assets; • Being less costly by orders of magnitude than to acquire, operate, and maintain U.S. Governmentowned assets and intermodal systems for the sealift mission, thus performing the military logistics mission in a significantly more cost effective manner; and • Ensuring U.S. military cargoes access to a global intermodal system that is continuously modernized by its commercial owners, without government assistance (which in any respect is beyond the capability of the U.S. government or military to replicate). Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom/New Dawn The extended and extensive sealift operations associated with Operations Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom/New Dawn (OIF) in Iraq have proven once again the benefits to the U.S. military of a strong, U.S.-flag commercial fleet and the value realized from MSP and VISA through which commercial capability is made available to the U.S. military. As a result, the share of dry cargoes delivered to U.S. and Coalition Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2002-08 by U.S.-flag commercial vessels increased from the 21 percent transported during the Persian Gulf Conflict in 1990-91 to 57 percent, while reliance on foreign-flag vessels dropped from 23 percent in 1990-91 to only 3 percent. The trend towards increased reliance on U.S.-flag commercial sealift to deploy and sustain U.S. and Coalition Forces in combat continued even as the focus of combat operations shifted from Iraq to Afghanistan beginning in 2008. Since 2008 the share of dry cargoes moved by the U.S.-flag commercial vessels has increased to 95 percent with the remaining 5 percent carried by U.S. Government-owned or controlled vessels. Whether by U.S.-flag vessels in commercial service or by U.S. government or chartered U.S.-flag vessels, since 2004 virtually 100% of all equipment and supplies for American forces in Iraq and Afghanistan has been transported by U.S.-flag ships manned by U.S. citizen seafarers. Most Cost Effective Means of Providing Sealift Few defense programs provide as much “bang for the buck” as MSP. The cost to the government of acquiring sealift capacity through MSP is less than 10% of what it would have cost the government to acquire, operate, and maintain equivalent sealift capabilities. In addition, because the MSF is capitalized and re-capitalized solely through the private investment of the owners and operators of enrolled vessels, the U.S. Government has realized almost $70 billion in capitalization and re-capitalization cost avoidance savings for the vessels and intermodal infrastructure capabilities provided through the MSP/ VISA. Total outlays in MSP payments for vessels enrolled in the program amount to only 2.5% of the benefit realized in investment cost avoidance alone. As retired Gen. Duncan McNabb, Commander, U.S. Transportation Command, USAF, recently stated, “[t]he partnerships with air and sealift companies is a very cheap way to maintain the military’s capabilities for war.” 10 17 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Defense Industrial Base: Shipbuilding The American Maritime Industry also contributes to our national defense No nation can support and sustain by sustaining the shipbuilding and a capable and sizeable Navy and repair sector of our national defense merchant marine without a strong industrial base upon which our standing and sustaining industrial base. as a seapower is based. History has Navy League of the United States proven that without a strong maritime Maritime Policy 2011-12 infrastructure —shipyards, suppliers, and seafarers— no country can hope to build and support a Navy of sufficient size and capability to protect its interests on a global basis. Both our commercial and naval fleets rely on U.S. shipyards and their numerous industrial vendors for building and repairs. The U.S. commercial shipbuilding and repair industry also impacts our national economy by adding billions of dollars to U.S. economic output annually. In 2004, there were 89 shipyards in the major shipbuilding and repair base of the United States, defined by the Maritime Administration as including those shipyards capable of building, repairing, or providing topside repairs for ships 122 meters (400 feet) in length and over. This includes six large shipyards that build large ships for the U.S. Navy. Based on U.S. Coast Guard vessel registration data for 2008, in that year U.S. shipyards delivered 13 large deep-draft vessels including naval ships, merchant ships, and drilling rigs; 58 offshore service vessels; 142 tugs and towboats, 51 passenger vessels greater than 50 feet in length; 9 commercial fishing vessels; 240 other self- propelled vessels; 23 mega-yachts; 10 oceangoing barges; and 224 tank barges under 5,000 GT. 11 Since the mid 1990’s, the industry has been experiencing a period of modernization and renewal that is largely market-driven, backed by long-term customer commitments. Over the six-year period from 2000-05, a total of $2.336 billion was invested in the industry, while in 2006, capital investments in the U.S. shipbuilding and repair industry amounted to $270 million.12 The state of the industrial base that services this nation’s Sea Services is of great concern to the U.S. Navy. Even a modest increase in oceangoing commercial shipbuilding would give a substantial boost to our shipyards and marine vendors. Shipyard facilities at the larger shipyards in the United States are capable of constructing merchant ships as well as warships, but often cannot match the output of shipyards in Europe and Asia. On the other hand, U.S. yards construct and equip the best warships, aircraft carriers and submarines in the world. They are unmatched in capability, but must maintain that lead. 13 18 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Defense Industrial Base: Seafarers & Shipyard Labor Maintaining a strong industrial base supporting the seagoing elements of the U.S. Merchant Marine and U.S. Navy includes having the trained and experienced manpower necessary to crew the vessels comprising the commercial merchant fleet and the skilled shipyard workers needed to build and repair both Navy and commercial ships. Thus seafarers and shipyard labor are key elements in maintaining U.S. maritime superiority. Seafarers To meet national defense sealift requirements, the U.S. Government requires a pool of trained, experienced seafarers to crew organic vessels activated from reserve or reduced operating status. The U.S.-flag commercial fleet provides that mariner pool. U.S.-Flag Fleet A strong national maritime industry also requires an education and training base to provide the skills and training necessary to develop and maintain a cadre of trained personnel for vessel operation and management. The key elements of the maritime education and training base in the United States for both commercial and military seagoing officers include the three Federal academies (U.S. Naval Academy, U.S. Coast Guard Academy, and U.S. Merchant Marine Academy) and six State academies (Maine, Massachusetts, Fort Schyler (NY), Great Lakes (MI), Texas A&M, and California). Shipyards The facilities in the largest private shipyards in the United States are more than adequate to produce the ships currently assigned. There also is some limited surge capacity in existence, but personnel and equipment for the ships are the limiting factors. Our naval shipyards have suffered for decades with little to no facility upgrades. The labor pool possessing the critical skills necessary to produce our equipment and systems and construct our warships is aging, with key personnel leaving and not being replaced in kind. Ship construction and related industries are not viewed by the younger generation as the place to be in today’s markets. The key element to achieving on-time and on-price production for our technically advanced systems and ships is a trained and dedicated work force. These shortages can result in all too common poor performance experienced in shipyards and manufacturing plants. The only solution is additional training and education at all levels. Entry-level training alone is not sufficient. 19 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Homeland Security The maritime industry in America contributes to our homeland security by: • Protecting critical national infrastructure; • Serving as the “eyes and ears” of Maritime Domain Awareness; and • Its readiness to mobilize to protect lives and property when disaster strikes. Critical National Infrastructure Domestic transportation is among the eight critical national infrastructures identified as vital to our national economy. Historically the United States has imposed heightened requirements over domestic industries constituting these infrastructures. By requiring that ships operating in domestic transportation and marine services be owned and operated by American citizens, the Maritime Industry helps ensure national control over the marine portion of that infrastructure. Maritime Domain Awareness The maritime industry provides the first line of defense for reporting suspicious activity observed around the nation and the world during the course of normal commercial maritime operations. Maritime Domain Awareness refers to collaborative information collection and sharing between the maritime industry, federal, state, and local authorities, and the general public. America’s coasts, rivers, bridges, tunnels, ports, ships, military bases, and waterside industries are all potential targets. Though our waterway security is better than ever, we have more than 95,000 miles of coastline, 360 ports, 3,700 cargo and passenger terminals, and over 290,000 square miles of water to protect. The purpose of America’s Waterway Watch is to use the “eyes and ears” of waterfront users, the thousands of crew members on vessels in domestic commerce, the 70 million U.S. recreational boaters, marina operators and other waterfront concessionaires, to detect and report suspicious activity that may be terrorist-related. Disaster Response America’s maritime industry has repeatedly mobilized in the face of disaster to protect lives and property. In addition to the massive boatlift during the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks (discussed earlier in this report) the industry responded urgently to the massive Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Gulf Oil Spill (2010) Following the Deepwater Horizon fire and sinking in the Gulf of Mexico, the American maritime industry again responded to help protect lives and property. Literally thousands of American ships and vessels of all types ranging from converted fishing trawlers and recreational craft to large Offshore Support Vessels were mobilized to fight the initial disaster, to stem the flow of oil from the well, to protect beaches and wetlands from advancing oil, and ultimately to recover tons of oil residue from the waters of the Gulf and along its shorelines. 20 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. The Past As Prologue Before there were highways and rail lines along our coasts, vessels of all sizes were the only means of transportation for freight and passengers. As increasing congestion on America’s highways and rail systems along those coasts threatens economic growth, our marine highways offer an under-utilized transportation asset that could help our economy to continue to grow. Only a truly seamless, integrated, multimodal transportation system will meet the nation’s growing needs. Navy League of the United States Maritime Policy 2011-12 As U.S. international trade increases it will result in higher demand for associated high service infrastructure such as container handling capacity at ports, and seamless multimodal connections to highways and railways and increases demand for inland transportation infrastructure such as highways and railroads. The role of the Maritime American in domestic commerce can be expanded much further with the advent of the Marine Highway Initiative (MHI). The MHI is just one example of how waterborne transportation must be a solution and work in conjunction with other modes to ensure the free-flow of domestic and foreign commerce in the United States. Waterborne transport can alleviate congestion along the nation’s highways. It can add to the efficiency and flexibility of global and domestic supply chains, as seaborne shipping does not require fixed infrastructure aside from ports. Since waterborne freight transportation is a far more fuel-efficient mode, it is also part of the solution to alleviating environmental problems and dependence on foreign oil. 21 America’s Maritime Industry The foundation of American seapower. Governments at the federal, state, and local level, regional transportation authorities, and the Maritime Industry are working collectively through the America’s Marine Highway (AMH) initiative to better utilize the great natural “highways” available on our rivers, coasts, and the Great Lakes to meet growing transportation needs. Sea Grant Michigan, “Great Lakes Jobs: Vital to Our Economy”, (2011). 1 Texas Transportation Institute, “A Modal Comparison of Domestic Freight Transportation Effects on the General Public,” (As Amended 2009). 2 IHS Global Insight, “An Evaluation of Maritime Policy in Meeting the Commercial and Security Needs of the United States” (2009) at 6. 3 4 Maritime Administration, “U.S. Water Transportation Statistical Snapshot”, Washington, DC (2011). 5 IHS Global Insight, ibid., at 10-12. Maritime Administration, “A Vision for the 21st Century,” Washington, DC (2007) at 5. 6 American Maritime Partnership (AMP) website under “Facts and Figures”. 7 See, e.g., Martin Study for Association of American Port Authorities, American Waterways Operators, American Trucking Associations, Shipbuilders Council of America, and Maritime Administration Statistical Snapshot. 8 Price Waterhouse Coopers, “Contribution of the American Domestic Maritime Industry to the U.S. Economy,” (2009). 9 American Forces Press Service, “Commander Discusses ‘Jewell in the Crown’ of America’s Military”, October 28, 2008. 10 IHS Global Insight, ibid., at 24 updated to 2009 by Maritime Administration, “U.S. Water Transportation Statistical Snapshot”, Washington, DC (2011). 11 Shipbuilders Council of America website. 12 IHS Global Insight, ibid., at 24. 13 22