Title The learning centre: not just a part of the whole education

advertisement

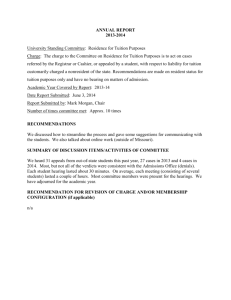

Title Author(s) The learning centre: not just a part of the whole education Tok, Feun Hannah.; 卓紹芬. Citation Issued Date URL Rights 2012 http://hdl.handle.net/10722/183372 The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights) and the right to use in future works. The Learning Centre: Not Just a Part of the Whole Education By Hannah Tok A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Education University of Hong Kong In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Education in Educational Administration and Management Supervisor: Dr Ng Ho Ming 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Ng Ho Ming for his insight, guidance, but mostly for his patience and kind understanding. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction Objective The Factors 4 5 6 Methods of Research Research Participants 1: Parents and Students Research Participants 2: Tutors and Teachers Data Collection Data Usage 8 8 8 9 10 Non-Mainstream Schools The Need for Flexibility and Adaptability It's Simple The Business of Being Human Size Matters Profound Learning versus Superficial Learning Social Capital Education as an Investment Servicing the Client Training and Passion 11 13 16 17 18 19 24 25 26 27 The Clients: Parents & Students Criteria for Selection Reasons for Tuition It's Cultural? 28 29 30 31 The Providers: Teachers & Tutors Some Revelations Organisation or Institution 34 34 38 Side-Effects of Tuition: A Personal Opinion 41 Conclusion 44 Appendixes A – F 45 References 59 3 Introduction They are featured on larger-than-life posters along the walkway of the MTR stations; on both sides of double-decker buses, and even billboards mounted on walls of shopping malls. They even invade the privacy of your own homes through flyers placed in letter boxes. Welcome to the world of "star tutors", this is the business of the learning centre – tutorial centre, for some – the secondary arm of education, and it is a booming industry. In a survey conducted by The Census and Statistics Department in Hong Kong, a third of secondary school students spent a staggering US$18.9m a month on private tuition for the academic year of 2004 – 2005 (The Associated Press). In 2011, it reached US$255m (The Express Tribune, July 5, 2012). As recently as July, 2012 The Standard reports 85% of senior secondary students in Hong Kong receive tuition (The Standard, July 5 2012). One Chinese media revealed that the collective salaries of Hong Kong's top 20 "star tutors" amounted to US$10m per month (The New York Times, 1 June 2009)! You may shake your head in disbelief, but with over 400 local schools and an approximately 20 ESF (English Schools Foundation) and international schools combined, there is still a huge chunk of the tuition pie that is still up for grabs (Appendix A). When presented with such figures, it is inevitable that one should ask why such a great demand for private tuition in a small city like Hong Kong? What invisible force, if any, is pushing this demand to such heights of fervour? What message are these numbers 4 sending out about the Hong Kong education system? And who or what is to blame – the government? The schools? Or perhaps the Asian culture, perpetuated by "Tiger Mom" meme, for stirring Hong Kong's perception about supplementary education? As a teacher who has taught only at international schools, I often wondered about this phenomenon: Was tuition-mania unique only to the local school students? I was convinced that it was because these "star tutors" were speaking directly at this group of students when they made promises of "As" in the HKCEE examinations. But after an experimental phase of full-time tutoring at a learning centre for a year, the answer is an emphatic "no". The centre at which I worked marketed themselves as educators well-versed in all sorts of international curriculums, particularly curriculums taught at the 20+ ESF, international and independent schools, also known as non-mainstream schools (NMSs). In 2010, when the centre started its operations in Wanchai it had just four full-time tutors, one of whom was the founder. Interestingly enough, even before the official opening celebration of this centre, there were plans and projections for another centre in Kowloon. The stakeholders of this centre obviously believed that there was demand to justify another branch. It has since set up a branch in Mongkok, Kowloon. Objective There is an old saying, "The sum of the parts is greater than the whole". The learning centre, is a part of any education system. Whether its role complements with or competes against schools, is subject to one's viewpoint about supplementary education. 5 It, however, cannot be denied that the humble centre has much to offer in terms of practical lessons in management and administration to educators. Consider this: learning centres like King's Glory Education Centre and Beacon College have long established themselves as household names with Hong Kong students. They employ aggressive marketing strategies, evidenced by the overt in-your-face advertisements of their popular tutors. Despite this given scenario, many relatively unknown learning centre continue to survive in such a highly competitive environment. Learning centres provide the service of supplementary tutoring, or "shadow education" primarily to two niches of students: 1. students who attend mainstream schools and take the Hong Kong local examinations, and 2. students enrolled in the ESF, international or independent schools and sit for internationally recognised examinations. The latter group will be the focus of this paper's discussion in reference to "the learning centre" from hereon. This paper will argue that the learning centre is a micro version of a typical functioning school, and as such educators can learn valuable lessons – not business strategies – about how to stay relevant and competitive in the 21st century. The Factors In order to have a better understanding of the mania surrounding learning centres, we need to examine some of the contingent factors vital to its survival. Perhaps then we would be able to unravel some of the questions raised at the start of this paper. 6 The factors that are predominantly responsible for this phenomenon are: 1. the nonmainstream schools (NMSs); 2. the parents and students, and 3. the tutors and teachers. These three groups operate as co-dependents of the learning centre for obvious reasons: each is mutually and interdependently entwined. The learning centre is dependent on parents and students to ensure its survival. The parents and students for various reasons, turn to the learning centre to meet their needs. And finally, tutors or teachers who provide the service of supplementary education. Like a giant jigsaw puzzle, each group holds a piece which when put together, will present the reader with a sensible and clearer understanding of the phenomenon known as the learning centre. Disclaimer: The term "private tutoring" or "private tuition" refers to students seeking academic tuition at learning or tutorial centres. This is not to be confused with private home tutoring or home tuition. 7 Methods of Research My research subjects will include primarily parents, students and teachers. The number of participants will be kept to no more than 10 from each group, making it a total of not more than 30 participants collectively, as this research paper is written at a master's degree level. As such, there must be deliberate constraints to the scope and depth. The selection process of these participants will be based on recommendations by friends or colleagues. I would like to use the following method in my research: Interview Research Participants 1: Parents and Students The rationale of interviewing parents and students is to have a better understanding of their motive for enrolling at such centres. While the pursuit of academic excellence is undeniably the obvious reason, are there other secondary reasons? Research Participants 2: Teachers As the school's core educators, it is important to know what they think about students enlisting the help of tutors at these centres. Do they see it as a partnership in assisting the students learning? What insight will they offer us in understanding students motivation, and teachers attitude to learning centres? 8 Data Collection The materials collected from the interviews will be recorded by hand on paper in a notebook, and no recording device will be used. In order to get an unbiased opinion on this subject, it is important that the participants feel unthreatened and relaxed to share his/her view freely. The idea location, therefore, would be in the comfort of their own homes and/or over the phone during the summer vacation. By being away from the school environment, participants would ideally be in a less stressful state of mind. Once the materials are collected, it will be stored for no more than six months before they are discarded in the paper shredder. Again, confidentiality will be ensured at all times during the interview by referencing each participant in the following manner as an example: 1. For parent participants: Participant: Name: Child/Children: Location: Parent A, female Mrs 1 Grade 8, male, at an IB international school in the south Conduit Road, Mid-levels Central 2. For student participants: Participant: Name: Grade & school: Location: Student A, male Charlie Grade 8, IB international school in the south Conduit Road, Mid-levels Central 9 3. For teacher participants: Participant: Name: Nationality: University major/s: School: Responsibilities: Location: Teacher A, male Mr A American English Literature and History IB international school in the south English Teacher of MYP Year 5, and DP Year 1 Taikoo Shing Data Usage The collected data could be reviewed and ideally presented to some school administrators, as a follow-up, after completion of the project. The purpose for doing so is to assess their reaction and weigh their response against the information from parents and students. Similarly, data collected from interviewing teachers will be used as during the interview with school administrators. It is imperative that administrators know the reasons in order to make adjustments, accommodations or improvements to enhance students' learning. Due to the sensitivity of the research topic, I do not anticipate administrators to be willing participants in this research. However, any information from administrators will be reflected in this essay as a note of interest. 10 Non-Mainstream Schools (NMS) The curriculums being offered by non-mainstream schools (NMSs) are viewed as an attractive option to the Education Bureau's HKDSEE (Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination) by many local Hong Kong citizens. With no intake restrictions imposed on locals unlike some countries, Hong Kong citizens may freely apply for a place at any of these schools. The general perception is that the internationally recognised curriculums – such as the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) and/or the International Baccalaureate (IB) which includes the Middle Years Programme (MYP) and the Diploma Programme (IBDP) – are more superior, and allow for hassle-free university applications to foreign universities. As a result, each NMS has an average student population of 1000 students, and hires approximately 60 to 100 teachers and around 50 support staff (Appendix B). An education institution of this size, or any organization for that matter, needs a system with clearly stated guidelines that will reduce chaos, ensure stability and efficiency. It would have to have a hierarchical flowchart of authority and accountability; a clear division of labour; written rules; a set of kept records, and a level of impartiality. In other words, a framework that possesses the characteristics of a bureaucracy (Weber, 1947). In relation to educational administration this is translated into, for example, rules and regulations for students, and a professional code of conduct for staff and teachers to adhere to. 11 This method of organizing human activity, as conceived by Weber, ensures rationality in all decision-making processes. This is especially important in the handling of school expenditure as demonstrated by a particularly embarrassing incident in 2003 which involved three ESF executives (Box 1). This incident also justifies Weber's point that when the impact of human emotion and sentiment is minimized, organizations are free to attain "the highest level of efficiency" (Schlechty, 2009). Box 1 The lavish lunch that bit back (HK Edition) Updated: 2010-10-27 07:01 A sumptuous lunch of oysters and wine seven years ago flavored people's opinions about the alleged extravagance of ESF executives - an image the organisation has been working hard to rid itself of since. The meal at the DotCod seafood restaurant in Central was shared in 2003 by three ESF executives and included 12 oysters, two bottles of wine and a bill for HK$2,300 which former chief executive officer Jonathan Harris refused to approve when it landed on his desk as an expenses claim. A leaked letter from Harris to ESF chairman Jal Shroff said that he also refused to sanction a claim for 17 drinks taken between 4:08 pm and 7:02 pm at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club for two of the same three executives and one other ESF official. Months after the letter was leaked, the Audit Commission issued a highly critical report on the management and finances of the ESF, pointing out that the average annual pay of HK$947,400 for teachers was higher than for seven other international schools in Hong Kong. It also revealed how a selection of senior management staff and school principals had annual entertainment expense budgets ranging from HK$8,288 to HK$28,411. The staff involved used up all or most of their budgets, the report noted. (Source: www.chinadaily.com.cn). 12 The organization chart of a typical NMS may look like this: Board of Governors Principal VP (Administration) VP (Finance) VP (Pastoral) VP (Curriculum) Secondary School Head Deputy School Head Head of Dept (English) Head of Dept (Chinese) Head of Dept (Maths) Head of Dept (Science) Head of Dept (Humanities) Head of Dept (Creative Arts) Subject CoOrdinators Level Heads Teachers Teaching Assistants Students The Need for Flexibility and Adaptability From the viewpoint of the administrator, the bureaucratic system with all its merits is the ideal framework for such big schools. The general consensus of the parents, students and teachers who I interviewed, suggests that it is not an opinion they necessarily share. The most common complaint is that schools are impersonal and rigid. Mrs 1, whose daughter Angela, a Year 11 student, attends school at an NMS in the south, recounts her experience with school bureaucracy, "My daughter had participated in an inter-school debate, and the rule required a teacher-supervisor to accompany her 13 to the competition. As a representative member of the school debate team, I had expected the teacher-in-charge of the debate club to be the team's teacher-supervisor. Because the competition was held on a Saturday, the teacher refused to go on the basis of the conditions on her work contract. The teacher kept insisting that she was under no obligation to chaperon my daughter to events independently registered by the student and not the school! No amount of coaxing or reasoning could change her mind. The teacher adamantly stood her ground, she would rather my daughter be disqualified from the competition than sacrifice a few hours". In the end, it was Angela's tutor at the learning centre who went with her – "for a price, of course". Mrs 1 attempted to express her disappointment with the school by making numerous phone calls to the school principal. She was told that the teacher was simply following the school's policy. A majority of the student participants interviewed commented that the rules in their schools seemed designed to keep their teachers out-of-reach to the general student population. The teachers are either logistically inaccessible to students ─ the teachers' room is in a different block or in a restricted area off-limits to students – or there are cumbersome policies to follow: students must make prior arrangements to meet with the teacher, no impromptu requests will be accepted. "As a DP student, I have some slots in my schedule for self-study. Sometimes I'm working on a question and could really do with some help, but if I don't have an appointment with my teacher I'm pretty much left on my own to figure things out", laments Sean, a second year DP student. 14 But he is quick to add that not every teacher is dogmatic about that rule. "Ms B is my English teacher and my Extended Essay supervisor. She knows we are struggling with IBDP, so she avails herself to us. But there were rumours that she was reprimanded for her 'indulgent ways'. Guess that's probably why she's doing most of her work in the classroom these days." We see from the above interviews that if schools follow strictly the typical model of bureaucracy, they run the risk of producing a rigidity of structure (Albrow, 1970). This structure, which places constraints on flexibility and adaptability can have polarizing effects on students, teachers and the school. The key, therefore, is to maintain the right balance. Now consider the learning centre. The following shows the standard organization chart of eight popular learning centres with NMSs students: Founder Full-time Tutors/Subject Co-ordinators Educational Consultant Part-time Tutors Students At first glance, the learning centre has a similar hierarchical framework as the NMSs; the noticeable difference is in its simplicity. This flat organizational structure is made possible only because the learning centre is a much smaller entity compared to the NMSs. The learning centre is in the business of providing students with supplementary 15 educational help. As such, there is no need for a discipline master, an activities coordinator, and other division heads. This simplicity affords many advantages to the learning centre. For one, it cuts away the traditional bureaucratic red tape, and it allows room for flexibility. Box 2 The Learning Centre as a School According the Education Bureau (EB), the learning centre falls under the category of a private school. Like all other educational institutions, it is subject to the EB's registration process and regulations(source EB). There is no specific distinction between a learning centre and any NMS. Every teacher has to be registered with the EB before embarking on any teaching assignment at the learning centre. (Source: www.eb.gov.hk) It's Simple Jason, a final year DP student who has been attending the same learning centre for 3 years, has this to say, "Whenever I show up early at the centre for tuition and my tutor's still in class, the receptionist would allow me to use the conference room to do my homework. Sometimes I'll just chat with other tutors or Elsie while I wait; they're always so willing to give advice on college application or anything! They are genuinely interested in you, unlike the teachers at my school." Elsie, the educational consultant, concurs, "Rigidity doesn't work here; not with our students, and certainly not with our staff. Every tutor and staff is a capable of exercising professional discretion, and we are encouraged to talk with students. 16 "We get a fair bit of students like Jason who drop in without an appointment to talk about college application. These kids have so much on their plate so we try to be understanding. If, during the course of conversation, we sense that it's not just a casual chitchat, we'd advise them to arrange for an appointment with their parents to come in for a formal discussion." The Business of Being Human The success of any service-oriented organization's survival and continuity is highly dependent on its ability to exude a sense of warmth, intimacy, and humanness. Elsie's learning centre understands how vital this is and that is why students like Jason feels so comfortable with her and his tutors. "The tutors are so friendly, and approachable. You can just be yourself when you talk to them; like you talk to friends, except that they're smarter!" By cultivating a sense of humanness, the learning centre becomes the antithesis of the bureaucracy which practices impersonality as one of its main characteristics. Thus revealing one of the advantages that the learning centre has over the NMSs. One can argue that the major challenge the school faces is the large enrolment of over 1000 students, making it virtually impossible to implement such a practice. The answer could lie in reviewing regulations and policies, and weeding out those that potentially threaten the collegial environment of the school, like rapport between students and teachers. Policies should not have an intimidating effect on personnel either, as it clearly 17 did to Ms B who felt she could not interact freely with her students without risking the disapproval of her superiors. Size Matters Small class size teaching is a unique feature of the learning centre. In Table 1 of the next section, The Clients: Parents & Students, we see that the learning centres offer a variety of tutorial options ranging from individual one-on-one with the tutor, to small groups of 4 to 6 students per session. It is interesting to note that most parents and students prefer to pay more for the individual one-on-one option over the small group. An explanation for this perception stems from the belief that there are merits in small class teaching, although there is no conclusive evidence to prove this to be true (Bray & Lykins, 2012). In an article written by Ehrenberg et al., parents may think that the number of students in a class has the potential to affect learning because of how the class size affects the teacher's allocation of time and effectiveness. Since it is easier to focus on one individual in a smaller group, the smaller the class size, the more likely individual attention is given, in theory at least (Ehrenberg et al., 2001). Marcus' father, Mr 3, appreciates the weekly individual tutorial sessions because "my son has a mild learning disability, and coming here has helped Marcus cope with the work at school." Experts may concede that small class size teaching is beneficial for students with Special Needs. But what about students without Special Needs? Ms F, a full-time school teacher, notices that some of her students are usually reticent in big group setting. 18 These students rarely participate in class discussions, if at all. "They just don't seem comfortable with the idea of speaking up. But when you get them on their own or with their friends, you'd be surprised by how articulate and smart they are. Unfortunately, it is also these few individuals who suffer in silence if they can't cope because they don't ask questions! And not every teacher has the time to go over the points with them individually. As such, I believe they would definitely benefit from private tuition." Regardless if the viewpoints are psychological, the general consensus from interviewing all three groups of participants believe that the dynamics of small class teaching makes room for great communication and coherence between student and tutor, thereby allowing real learning to take place at tuition centres – a crucial point about the learning centre. Profound Learning versus Superficial Learning The curriculums IGCSE and IBDP, especially the latter, are considered to be challenging and demanding. An excerpt, taken from Wikipedia, describes the IBDP as: "…a rigorous, off-the-shelf curriculum recognized by universities around the world” when it was featured in the December 18, 2006, edition of Time titled "How to bring our schools out of the 20th Century". The IBDP was also featured in the summer 2002 edition of American Educator, where Robert Rothman described it as "a good example of an effective, instructionally sound, exam-based system." Howard Gardner, a professor of educational psychology at Harvard University, said that the IBDP curriculum is "less parochial than most American efforts" and helps students "think critically, synthesize 19 knowledge, reflect on their own thought processes and get their feet wet in interdisciplinary thinking." The IBDP curriculum conducts assessment procedures that measure – apart from academic skills – students' ability to analyse information, evaluate arguments, and solve problems creatively (www.ibo.org). Most schools, the NMSs notwithstanding, follow a primary mode of learning that goes something like this: groups of students of the same grade level or year group in a classroom, or a laboratory, interacting with a teacher teaching and conducting activities directed toward learning a particular topic within a set framework of time. Given such a scenario, how do NMSs provide students with a learning environment to achieve all the abovementioned IBDP goals? In his book, Leading for Learning, Philip Schlechty discusses two types of academic learning: profound learning and superficial learning (Schlechty, 2009). He explains: Profound learning affects and shapes habits and worldviews; it is learning that involves the ability to evaluate and create, as well as to compare, contrast, and remember, and can be used in a variety of contexts. Superficial learning involves short-term memory. It provides little in the way of application in novel contexts. Superficial learning is compartmentalized rather than embedded in worldviews and habitual ways of thinking and doing. It does not require much in the way of commitment, meaning, persistence, or voluntary effort. All that is required is student compliance and a means of inducing students to spend sufficient time 20 on task to "master" the involved operations well enough to respond appropriately on paper-and-pencil tests. Schlechty continues with his observation about bureaucratically organized schools: Bureaucratically organized schools are ideally situated to produce superficial learning, focused as they are on compliance. Bureaucracies are not, however, proficient at fostering the conditions that promote profound learning. Profound learning requires a certain tolerance for ambiguity, an acceptance of uncertainty, and a degree of playfulness not found in a bureaucratic system. It is for these reasons that I argue that if schools are to serve society well, they must be transformed into learning organizations. Schools must provide students with intellectually engaging experiences that result in profound learning. This is learning that lasts and has meaning beyond the classroom in which it was learned or the test to which it was oriented. Learning organizations provide such conditions. Bureaucracies do not. Such a learning environment does not exist in a vacuum, it needs to be fundamentally supported by teachers and a system that give students a holistic learning experience to meet their educational needs. Such an environment is especially relevant in the IB context. Mr D, a former teacher, and now founder and co-owner of a popular learning centre in central, explains that his learning centre is about "being innovative" and "creative". 21 After teaching IGCSE and IBDP English for four years, he concludes that his former school's system, regardless of the curriculum, stifles students' ability to think for themselves. "Ultimately, it comes down to the grades. Parents demand them, and the school expects them. When you're pressurised to complete the syllabus and deliver the grades, there's just no room for critical thinking activities, unless it's part of the syllabus. Some of my former colleagues resorted to rote learning to maintain a healthy pass rate for their department. Quite frankly, I disapprove of this but I don't blame them." If Mr D is suggesting that the lack of pressure helps create a conducive learning environment, it certainly seems the case when I took up his invitation to tour his centre. I also took the opportunity to interview with some of the students about their view on learning in school and at the centre. Observe some of their responses: 1. "Tutors make the lesson relational." Ideas or concepts are broken down into piecemeal and explained in terms that students find it easy to understand, and relate. 2. "There's no pressure." Tutors work at the student's pace with the objective of helping the him/her understand. In a one hour tuition session, for example, the tutor is not compelled to complete a specific number of tasks, nor is the student made to answer a set number of questions within that time frame. It is student-centred, not task oriented. 3. "It's fun." The learning centre is not bound to any fixed curriculum, so there is flexibility in implementing activities to engage students in the learning process. There are more opportunities for discussions, debates, and discourses with the tutor. 22 4. "The tutors are patient." When tutors understand their role is to help the student, they become an instrument to guide and not direct them in critical thinking, for example. While these methods apparently work in raising learning for these students, perhaps the challenge is for NMSs to review how they can implement them in creating a learning environment for their own students? It is no wonder that there is much debate about how to maximise the amount of student learning, since resources – most notably, time – are required for learning, and are scarce (Ehrenberg et al., 2001). 23 The Clients: Parents & Students In the study of economics, we learn that the law of supply and demand is first and foremost, a theory which explains the interaction between the availability of a resource and the demand for that same resource (Investopedia.com). Generally, if there is a low supply and a high demand, the price will be high. Conversely, the greater the supply and the lower the demand, the lower the price. The table below shows the price range of eight learning centres⁺ in Hong Kong. The charges of these learning centres vary, but their fee structure is determined primarily on the grade level or year group in which the student belongs. Table 1 Grade Level or Year Group MYP Year 1 to Year 4, or equivalent MYP Year 5 IGCSE IB Individual session with tutor $600 ─ $650* per hour⁺⁺ Group of 4, up to 6 students $400 per hour⁺⁺ $650 ─ $700 per hour $650 ─ $700 per hour From $850 per hour $450 per hour $450 per hour $500 per hour * All currency in HK dollars ⁺⁺ Rates quoted by 8 different centres ⁺NB: The selection of centres is based on the popularity with NMSs students. The rates, based on per hour one-on-one session, can go up to $1000 with the centre's "senior" tutor, and up to $1300 with the subject specialist. Some centres even include a clause that there must be a mandatory minimum enrolment of 5 lessons for each subject. Interestingly, in addition to paying a 5-figure monthly school fee (Appendix C), parents are not deterred from enrolling their children at these learning centres despite their bold astronomical charges and mandatory clause. 24 The question that needs to be addressed at this point: What is the "resource" offered by the learning centre that arouses the desire of both parents and students? Is this "resource" an actual tangible good, or is it a service? What causes the demand for this "resource"? How is this desire generated? Is it real, or is it imaginary? Criteria for Selection The selection process of these parent and student participants was not based on their economic background, nor the size of the family. The most important criterion, as outlined at the introduction, is the enrolment of their child or children at a NMS. Based on the interviews with parent and student participants, my findings show that these participants share many common characteristics. These include: 1. All participants live in Hong Kong island, and are owners of their apartments. The measurement of their apartment is at least 1000 square feet in size. 2. All participants are either university graduates and/or have spouses who are graduates too. Half of those interviewed graduated from an overseas university. Half of them hold a post-graduate degree. 3. Half of the participants are working professionals, the other half are home-makers. The latter group does not contribute financially to the household income. 4. Many of them have either one or at most, two children. 5. Every household owns a motor vehicle. 25 6. Each of these participants spends an average of HK$10,000 a month on supplementary tuition per child. 7. Most of the participants have children either at senior school or at middle school. The youngest is at Grade 10. 8. None of the participants replied in the negative when I asked them if the cost of tuition had any adverse effect on their lifestyle. They continue to travel in summer, or take short trips as a family during term break. Based on the above findings, we can conclude that these participants are economically comfortable, educated, and affluent. Reasons for Tuition In order to find the answers for those questions earlier, I asked both parents and students their reasons for enrolling at a learning centre. While the pursuit of academic excellence seems undeniably the obvious answer, is that the only reason to explain their expenditure on tuition? Of the 10 sets of parents and students interviewed, only two parents signed their children up at learning centres for remedial help in their studies. Marcus, is an SEN (Special Needs) student who has been diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome. Wen, on the other hand, has English tuition because he had just transferred from a school that uses Chinese as the medium of instruction to an international school which uses English in all academic subjects. 26 The following table is a compilation of some of the commonly given reasons by parents and students: Table 2 Parents Reasons "I want my child to get into a top university/school/gifted programme." " This learning centre has a proven track record of success." "Other parents are doing it." "I don't want my child to lag behind." Students Reasons "My friends have signed up with this learning centre." "I like this subject, and want to learn more." "My teacher teaches the elementary stuff. I should be learning more challenging materials." "I want to be guaranteed good grades for university admission." "My tutor's explanation is really clear, and she's really smart. She always helps me to look at the problem from a different angle." "My tutor is very experienced. She's taught MYP/DP for years. She knows the syllabus very well." As we can see from the table of answers above, the need for tuition is more about competition; specifically, keeping the competitive edge over others, than remedial help. Of the 10 student participants interviewed, seven of them are high achievers. They have consistently maintained their academic standing in the top 10% percentile of their grade level, and have received academic awards and recognition from their schools and teachers. It's Cultural? Mr C, a former HOD at an NMS, is not surprised by this finding. "Asian parents don't enrol their kids in a school because it's got a good sports programme; they do so because of the school's reputation and performance in academic achievements. They 27 have an academic-centric outlook on education. They expect their kids to get into university; not just any university, but a top university. Western parents place a lot more value on non-academic programmes. Take a look at the international schools in Hong Kong, it's those western schools that have committed, solid sports teams. It's all about the culture." The dubious honour of being "academically driven" given to Asians is especially hard to shake off when Amy Chua explains to the world the success she has had in applying her strict Asian upbringing on her American daughters (Chua, 2011). While culture makes a convincing argument, there is still no conclusive evidence pointing to culture as the only reason for tuition especially when there are other factors and "forces of globalization" at work (Bray & Lykins, 2012). One of these factors, I believe, is as the result of human relationships giving birth to the concept of social capital. Social Capital It is defined as "the endowment of mutually respecting and trusting relationships which enable a group to pursue its shared goals more effectively than would otherwise be possible. It results from the communicative capacities of a group: something shared in common and in which all participate." (Szreter, 2000). The gathering of grade level parents at a school conference, members of the social club, and parents at a sports meet are just some examples of how networking can be established to generate social capital, particularly in which they communicate with each other. 28 The act of exchanging information does not just occur through personal encounters. Technology has given this generation of parents another platform to exchange ideas and keep them well-informed. With the availability of so many social networking sites, these savvy parents take to forums like www.babykingdom.com to enquire into, provide details of and even offer criticisms about all aspects of the NMS. Mr D, a former teacher, now founder and one of the co-owners of a popular learning centre remarks, "What is their (parents) favourite topic of conversation when they meet? Simply, their child's progress at school. It is not necessarily about grades per se, although that is important. Parents are more interested to know what is being taught at their child's school, and how it compares to other NMSs." The extent of this network goes beyond the circle of parents, it also includes building trusting relationships with the centre's tutors and staff, as the old adage goes: knowledge is power. Education as an Investment "One of the more common questions I've been asked is to explain the difference between IGCSE and MYP. This is usually followed by questions about IBDP, and what their child can do more – as opposed to should do now – to cope with the rigours of the course." By being proactive in asking, parents are quick to sign up their children for more supplementary help for future college applications. This preparation includes taking external examinations like the IGCSE or 'A' level as private candidates, and leaving the responsibility of bringing the grades home to the tutors at these learning centres. 29 These parents, predominantly in their 30s and 40s, are educated and most likely to have been part of the "YUPPIES" (young, upwardly mobile professionals) generation, understand that expenditure on education is not an end in itself but a means to an end: the future livelihood of their children. This act of investing in education, in this case, spending money on tuition, is an investment in human capital. Economists regard education as human capital because it is widely believed that the accumulation of knowledge and skills enables people to increase their productivity and their earnings – and in so doing to increase the productivity and wealth of the societies in which they live. The underlying implication is that investment in knowledge and skills brings economic returns, individually and therefore collectively (Becker & Becker, 1997). Servicing the Client Thus, the number of learning centres that offer more than just remedial tutoring is growing. They need to if they want increased economic returns. It is not uncommon to find learning centres that focus on diagnosing a student's weaknesses and offering individual support for organizational and study skills. Elaine, a final year DP student, shares how she has to resort to getting tuition for economics, even though her school teacher has a reputation of producing 6s or 7s. When asked if she has approached her Economics teacher for help, Elaine rolled her eyes and replied, "Mr A is a good Economics teacher, and I do get decent marks on this subject. But that's not enough, I really want a 7. In order to get that, I need help in 30 organising and expressing my ideas in the essays. I've approached Mr A on a number of occasions about this, but instead explaining how and where I could improve, he kept criticising my lack of effort in building up concept knowledge." "My tutor, on the other hand, is patient and understanding. After he had explained the rubrics, he went over each essay and explained why I wasn't getting top marks in each criterion. Everything became crystal clear. Mr A does a good job teaching the concepts, but my tutor has shown me to key to writing an effective essay. That's what tutors are for, right?" It is precisely not just the job of the tutor to help students like Elaine understand her weaknesses, it includes all her subject teachers. Yet, from the answers in Table 2 students seem rather apathetic to their teachers' limitations. Why is that? Training and Passion The number of Professional Development days per school year, varies from NMS to NMS. The objective of PD days, as they are called, is to provide teachers with skills and knowledge for effective teaching. However, many teachers do not agree that the objective has been met. "Most of the training I had were not relevant to teaching; there weren't even any workshops on planning and development. The training they provided were all task-oriented, there was no skill related learning," says Ms E. Without a budget, tutors at the learning centre do not get to enjoy the perks of attending all-expenses paid workshops, but they still manage to impress students with 31 their insight and knowledge. Mr D explains the difference is in the passion, "Teaching is a calling. You need to be genuinely interested in what you're doing. If you have that thirst for learning, you will naturally want to learn more. It is infectious and your students will pick it up from you; they have an inbuilt radar for this sort of things." Other teachers like Mr C does not agree that passion is the only answer, although he strongly believes that it is an integral part of teaching. According to Mr C, most NMSs have one fixed syllabus for each year group. Unlike tutors at the learning centre who have the luxury of variety, the teachers face the task of teaching the same book or topic every new academic year. After a while, the teacher gets jaded and bored. "One way to avoid that, get new resources – but it'll cost money." Box 2 Family Dynamics During the course of interview with parent-participants, I noticed they possessed the following similar characteristics: 1. Each parent admits to having certain expectations of their child – incremental progress in their subjects, in particular those subjects for which they have tuition. However, they do not resort to punitive measures when the child fails to do so. Instead the parents would engage in a constructive dialogue with the child towards understanding and solving the problem. 2. They monitor their children's academic performance closely, but they do not believe in being intrusive. They believe that their children should take ownership of their behaviour and consequently, be responsible for any desirable or undesirable outcome. 3. Both parent and child share a strong bond of mutual respect. The children are not resentful of their parents active involvement in their academic performance. In fact, they often feedback to their parents what was taught at the centre, and if their tutors were teaching them something beneficial. 4. All the student-participants expressed a strong preference to study law, economics, or medicine. They also entertain ambitious plans to be an entrepreneur ultimately. 32 Box 3 Day Care Centre or Social Hub? View 1: Critics of the learning centre say that it is nothing more than a day care centre. These critics, educators by profession, say that tuition centres feed on the guilt of dual income parents who enrol their children in different types of courses while they chase their materialistic dreams. With "extra disposable income" to spare, learning centres are taking full advantage of this. Other critics even liken the analogy of a day care centre to churchgoers who place their toddlers at the church's Sunday School for an hour or two while they happily practise their Christian value of giving at the restaurant or shopping malls. Ouch! A random survey conducted by a teacher friend of mine reveals shocking information about the busyness of students. A typical schedule comprises of tuition for English, Maths and Science (Chemistry or Physics, for older students) on weekdays after school. Music (usually piano), dance class, ballet, or Chinese tuition on Saturdays. Children as young as 10 have a sardine-packed schedule that makes one wonder if parents are robbing kids of their childhood? View 2: Students interviewed for this paper admitted improving their academic performance remains one of their top priorities for going to the learning centre, but they also pointed out that the people and culture of the centre is another big factor. "I don't have to be here on weekends, but I don't mind because my friends are here for the SAT prep class. It's a whole new environment here, I get to hang out with people from other international schools. It's like networking, actually. And you get to meet boys too!" "Even though I study at (name of NMS), I don't get to meet too many other students from the sister schools. And this may make me sound like a snob – but I'm not – I can speak English freely here without people giving me the evil eye or look at me strangely. At least the folks here know that Jersey Shore* is not a place!" *Reality TV show 33 The Providers: Tutors and Teachers Mr C, former HOD, resigned from his full-time teaching position at an NMS after 15 years in education. He was well-liked by all, and was even selected by the board of directors to join a senior leadership position. Mr D, "stumbled" into teaching when he substituted as an English language teacher at an NMS. The department head and principal were so impressed by his enthusiasm and his work ethic, they offered him a full-time position. After getting his PGDE at a local school, Mr D resigned from teaching the following year to set up a learning centre with some colleagues. Ms E joined the teaching profession after working in the service industry for two years. A fully qualified teacher, Ms E was hired to teach biology at a NMS near where she lived. Her contract included a monthly housing allowance, return airfare to her home country and gratuity upon completion of a 2-year contract. Ms E finished her contract, stayed an extra year with the school but decided to resign after the third year. With the exception of Mr D, both Mr C and Ms E have not returned to education in any capacity. They have not ruled out the option of going back to teaching in the future. Some Revelations The interviews with these three individuals were conducted separately, and these participants are not acquainted with each other. My first obvious question was, why 34 quit teaching? Surprisingly, all three gave me the same answer: Disappointment with the school. 1. Mr C "I joined teaching straight after graduating from university. You could say that I was a greenhorn because I was armed with many idealistic goals and ambitions. I wanted to put my mark on the world, and there's no better place to start then at school. I've considered myself to be innovative in teaching; students and colleagues alike often said I had the ability to energize my students. I had no problems engaging at their level, and it was true for them as well. I did, however, notice that some teachers did not relate quite as well as I to the kids. This is particularly true of the older teachers. It made me wonder if it was a question of communication, age, or attitude? After more than a decade of teaching, and now as the department head of humanities, I was making a very comfortable salary. And with additional allowance given to me for coaching basketball, the world was my oyster! But I wasn't happy. Teaching seemed to have lost the zest I initially felt 15 years ago. I was spending more replying to emails, dealing with administrative matters, or attending meetings. I had to stop coaching because the board and administrators felt the sooner I adjusted myself to the new leadership position next fall, the better. The school had become the only priority." 35 2. Mr D "I was a Theatre and English major at a university in the States. When I came back to Hong Kong, I approached my former English teacher for a job as a substitute teacher. I really wanted to go into theatre, but it isn't easy. After the school had offered me a full-time position, I was able to establish a greater sense of rapport between me and the students. And for the first time, I really heard the students; they spoke their minds and there was a lot of trust. I weighed all these in my head, and experienced with different pedagogical styles to improve their learning. My former teacher, who was the department head of English, supported my vision to be innovative and creative, but she warned me that if I wanted to change the system I would only be successful working from the outside and not within. I didn't want to be disrespectful, but I was determined to prove her wrong. As it turns out, she was right. It grew progressively harder to continue the momentum I had started after becoming a full-time teacher. There were deadlines to meet, and the system just didn't allow me to implement those ideas that I had. I became disgruntled with the school, and my students became disgruntled with me. It was such a vicious cycle, there was absolutely no learning. It reached a point I couldn't even listen to my own thoughts! There was no time for selfreflection either. And that's when I knew it was time to leave." 36 3. Ms E "My greatest gripe with my school is the fact that they are a "non-profit organization", or so it says on the website. But when you see corporate job titles like "Business Manager", or "Marketing and Publicity Manager" in a school, you just have to ask if the school is a business organization or an academic institution? It became very evident to me that the school was moving towards a corporate-like vision when the principal made an announcement about a fundraising event. The school went on a major publicity blitz advertising in the papers, putting up posters buses, and sending out letters to parents and flyers out in the neighbourhood. Why? Just take a look around you: we're located in a prestigious residential area. I understand the need for a big campus, and I fully support to have the school equipped with modern facilities. But what about investment made in promoting learning? There doesn't seem to be much enthusiasm in promoting the learning process amongst students. Take, for example, welfare and safety of my kids. If I wanted to purchase some equipment for my DP students, I would first have put down in writing and submit my request to the Science department. Once that is approved – it usually is because the state of our lab is so dire – I would have to fill up another form with details describing the merchandise, reason for the purchase, how many units to purchase, and the approximate cost of each item. The form would be 37 submitted to the vice principal of finance, all requests for moneys are subject to her approval, and there's no guarantee that the request would be granted. Are we running a school or a business corporation?" Organization or Institution? The vision and mission of a school can only be clearly articulated if the leader understands what the purpose of education is about, how children learn and sets out to convey this belief with conviction (Manley & Hawkins, 2010). The learning centre is a business organization in the business of education. They do not shy away from marketing their wares – their tutors – not unlike their local counterparts like Beacon College, except they do so less ostensibly. One visit to their website, and you will see a detailed résumé of each tutor's academic qualifications. Most of them were educated abroad, typically having graduated from North America universities. The centre continues to provide a list of impressive credentials and experience of each tutor. They are specialists in their respective subject. Such brazen advertising may be considered to be in bad taste, but as with profit seeking businesses you pay for what you get. With the exception of claiming to be a non-profit organization, most NMSs have adopted the practice of posting teachers' qualifications on their website, just like the learning centre. And each of them charges school fees that would be a stretch on the pockets of an average income household. Are the NMSs misunderstood educational 38 institutions, or are they really business organizations concerned only about "the bottom line" (Schlechty, 2009)? Mr 4 was visibly upset as he recalled the meeting with his son's administrators last year, "I was shocked when they advised me to consider transferring Ryan to another school because he wasn't making the school's projected benchmark for each grade level. That was the first time in seven years I had heard of any benchmarking. It didn't occur to me that it had anything to do with the new curriculum which the school had just introduced. They wanted to stay competitive against other international schools, that was the reason given to the parents. But when I found out that Ryan would be the first cohort of students to take the exams, and a poor performance would adversely affect the school's overall average. I knew then why we were served the exit papers." In that same year, nine other students received similar "exit papers". There is no way to find out if such extreme measures taken by schools to protect their reputation exist. However, it is a common practice of schools to upload the performance of their graduates unto their website. This gesture could be interpreted as a channel of communication to stakeholders of the school and members of the public. The cynic would say that it is just another form of advertising, and the goal of all advertisements is ultimately profit. When schools forget that their first obligation as an institution is to meet the needs and serve the values of those who are most directly affected by them: parents and students, then they run the risk of compromising their integrity and 39 reputation; providing students with an inferior education; and decreasing morale amongst teachers (Schlechty, 2009). The voices of Mr C, Mr D and Ms E are voices of discontent; discontentment with how schools are run. We have heard from them neither money nor promotion provides a strong motive to say. Consider the learning centre: When I asked the tutors at various learning centres what were the pull factors for remaining in their current situation as opposed to a full-time teacher, many replied "freedom". Freedom from what? "Freedom from the mountains of paperwork, freedom from nagging, unreasonable parents, and freedom from micromanaging administrators – to name just a few," says Mr G, a married man, father of two boys. "The epiphany came in the middle of the night to the cries of my first child at 2am, when I was still grading math papers! I asked myself if I could envision myself doing this for the rest of my life? My typical routine was to get in school by 6.45am. As head of department I wanted to be a good example to my staff, but getting in early also meant 'extra' time to check my school email, attend to the odds and ends. Because when school starts at 8am, I won't be able to get any work done. I usually got home at about 8pm, have dinner with my wife, see the baby and it's back to work. She goes to bed, while I'll be up marking. Sure it doesn't happen all the time, but it's happened enough to make me realise that it's time to move on." While Mr G's day at the centre officially ends at 8pm, the centre allows staff to leave if a student cancels or if they do not have a class. "It's about flexibility and trust," he concludes. 40 Side-Effects of Tuition: A Personal Opinion In Singapore, a discussion about government's involvement in the regulation of preschool is taking place. Some concerned citizens fear that the cost of preschool education is reaching astronomical proportions. There are currently 502 preschool centres, and the monthly fee ranges from S$55 (HK$342) to S$1800 (HK$11,120). One parent pays about S$1500 (HK$9330) each month for her six-year-old daughter to attend preschool. Her child also attends classes in art, violin and ballet (The Straits Times, Jul 28, 2012). What implications do such behaviour have for the generations of children to come? 1. The income gap between the rich and the poor will be considerably wider. As we have seen from the example above, some parents have no objection to paying a good deal of money for their children's education. The reason for this is simple: During the good old days of large families, the head of the household was the only breadwinner. Nowadays, couples stop at having one child, two at most. The combined salaries of two working professional parents with just one child, means the availability of more disposable income. But not every household can afford preschool or private tuition, which they consider a luxury. In the same article, a divorcee mother of one, brings home a monthly cheque of S$900 (HK$5600). For her, paying S$55 for the cheapest preschool would be a consideration she has to weigh carefully in her mind. She would have to think about the opportunity cost of what that same amount of money could buy for the family. 41 These two households show a stark contrast in the disparity between the rich and the poor. The six-year-old child in the first family is guaranteed to be more successful than the child in the second family, all things considered. As it is, she has a head-start in this rat-race. The returns on her mother's investment into this child's preschool education, will come in the form of confidence, network, social status and comfort, thanks to her mother's visionary outlook on what education can bring. Not so fortunate for the other child. Unless she meets with a wealthy benefactor, chances are the divorcee's daughter will perpetuate her mother's life story. In other words, history will repeat itself. This is not just a sob story about a rich girl and a poor girl. This is a potentially catastrophic situation facing the world today. A rising trend in tuition will lead to an imbalance between skilled and unskilled workers. With too many graduates in the market, the future could see a glut of professionals in a particular sector, and a dearth in another. A situation like this will drive the salary of the former group down, and the latter up. Thus, the vicious cycle continues. 2. Social retardation? An unhealthy obsession with success and competition is changing the demographics of students enrolled in learning centres: They are getting younger. The example of the sixyear-old child's tight schedule is no longer an exception, but a norm. Just like her, many little girls and boys' weekends are filled with classes in violin, art, and ballet/swimming. 42 As parents, these adults have the right to be involved in the lives of their children, especially when they have not developed mental maturity which would help them to discern or make their own decisions. But when parents meticulously plan a schedule that does not allow play, they inevitably stunt the emotional development of the child, thereby adversely affecting their cognitive skills and creativity. The much needed interaction with other children is now replaced with books and adult tutors. Technology has already provided convenient ways alienate ourselves from the real world. We do not need more social retardation from excessive tuition. 43 Conclusion There was a time when students cringed at the thought of going for tuition. It meant that you were not as intelligent as your peers. That was a very long time ago. Today, tuition has taken on a new meaning and it even has a new name: supplementary or shadow education. Students no longer shy away from admitting that they have tuition because it no longer means you are not smart, but au contraire, you are. It is the pursuit of knowledge that you are after, and you understand that with knowledge comes power: economic power and academic power. One source of this power comes from the learning centre, a miniature version of the school. As we have read in the paper, the learning centre does not exist in a vacuum. It is interdependent of other factors and forces, it affects and is, in return, affected. The learning centre understands that it needs to constantly adapt to the changes to the environment in order to survive. It cannot remain static. The learning centre is not without any limitations. Unlike the non-mainstream schools, to which it is compared in this discussion, the learning centre does not enjoy the economy of scale that is afforded strictly to large organizations. As such, the learning centre learns how to be resilient and relevant during such economic turbulence. This paper describes, in part, how the learning centre adjusts and adapts to the various changing elements in the environment, and how non-mainstream schools can learn 44 from it. Education is and should be dynamic, and as educators we have to respond accordingly. Failing to do so, we fail as teachers. Sadly, too many schools become complacent because they know they are indispensable. With complacency, apathy. As long as there is demand, there will always be supply and the demand for places in non-mainstream schools is very high. The waitlist, on average, can be three years. Perhaps it is this demand that has blindsided administrators to shift their focus from the school as an institution, to the school as an organization. The lifeline of schools is not the sprawling campus, the state-of-the-art technology, the modern facilities – characteristics of the non-mainstream schools – it is quite simply, people: students and teachers. People who appreciate the real meaning of learning build up a school's reputation in performance and achievement. Like ripples in a pond, the name of the school spreads and demand will follow. Perhaps it is time schools wakeup to this reality. Let us not be blasé about what really matters. 45 APPENDIX A: Secondary Education School year 2006/07 2010/11 2011/12 No. of Schools Local ESF & other international 503 25 506 27 497 27 528 533 524 255 992 161 461 63 322 - 223 177 161 172 65 388 - 208 010 227 278 31 799 480 775 449 737 467 087 18 016 18 120 14 020 5 507 2 960 2 932 38.0 30.2 - 34.4 30.1 - 33.0 29.5 26 984 1 650 29 219 750 30 867 697 28 634 29 969 31 564 Percentage of Trained Teachers(2) 94.2% 94.4% 93.5% Pupil-Teacher Ratio(2) 17.0:1 15.2:1 15.0:1 Total Student Enrolment(1)(4) S1-S3 S4-S5 S4-S6 S6-S7 S7 Total No. of Repeaters(1) No. of Children from the Mainland Newly Admitted(2)(3) Average Class Size(2)(4) S1-S5 S1-S6 S6-S7 S7 No. of Secondary School Teachers(1) Degree Non-degree Total 46 Wastage Rate of Teachers (%)(2) [Percentage of teachers of the previous school year who did not serve in schools in the 12-month period prior to September of the respective school years] Trained Untrained Overall 5.2% 19.6% 5.2% 16.4% 3.9% 11.2% 5.9% 5.9% 4.3% Notes : Figures in this table do not include evening schools, special schools and secondary day courses operated by private schools offering tutorial, vocational and adult education courses. Unless otherwise specified, figures refer to the position as at the beginning of the respective school years. (1) Figures include statistics of local, English Schools Foundation (ESF) schools and other international schools. (2) Figures exclude statistics of English Schools Foundation (ESF) schools and other international schools. (3) Figures refer to One-way Permit Holders who admitted to schools during the 12month period prior to October of the given school year. For example, figure for 2011/12 refers to admission during October 2010 to September 2011. (4) The New Senior Secondary academic structure has been implemented fully in 2011/12 school year. Sources : School Education Statistics Section, Education Bureau Central Team /School Development Division, Education Bureau 47 APPENDIX B: List of International Schools The English Schools Foundation Island School West Island School South Island School Shatin College Chinese International School Canadian International School Singapore International School French International School Victoria Shanghai Academy Independent Schools Foundation Hong Kong International School German Swiss International School Korean International School Yew Chung International School 48 APPENDIX C: Table showing school fees for ESF and international schools and that of local schools in Hong Kong. All amounts are quoted in HK$. ESF International Schools Independent Schools CIS YCEF CDNIS Middle School Senior School $98000 paid over 10 $102,000 paid over 10 months months $171,000 $173,400 145,450 (not updated) 171,000 144,960 124,100 & 134,800 Debenture 160,000 (not updated) 173,400 148,280 134,800 + 5,500 For 2011/12 school year, the yearly total for DP (Y11-Y12) is HK$118,770. For Y11, each of the 10 instalments is HK$11,877. For Y12, each of the 9 instalments is HK$13,197. 49 APPENDIX D: Interview questions for parents A: Background information: 1. How many children do you have? - How many of them receive tuition? What are their ages, grade level? 2. For how long have they received tuition? (Months, years?) - Why so early? Or why so late? For what subjects do they have tuition? 3. How often do they have tuition for the subject/s? - How long is each session? Is it a group session or one-to-one session? Reason for your choice? How much per session? Do you think this rate is acceptable, low or exorbitant? Why, why not? 4. How much money is spent on tuition per month? 5. Has the monthly expenditure on tuition affected your family's lifestyle adversely? For example, sacrifices made on family vacations, etc. 6. What role/s do learning centres (LC) have in your child's academic performance? - What sort of expectation do you have of LCs? More than the school? Less? No expectations? Why, why not? The school 1. Please state if your child is enrolled in an ESF, international or independent school. 2. When did your child enrol in this school? - What was the reason for the enrolment of this particular school? How many years has your child been with this school? 3. Has your child always studied in a non-mainstream school? 50 - If yes, why? If no, why not? 4. What were the primary reasons for enrolling your child in ESF/international/independent school? 5. How satisfied are you with your child's academic progress in this present school? 6. Do you have any expectations of the school and the teachers? - If yes, what are they? If no, why not? 7. Are you satisfied with your child's teachers? - Why, why not? 8. Are you satisfied with your child's school? - Why, why not? 9. In addition to paying the high school fees these institutions charge, you are also making extra payment for additional tutorial for your child. - How compatible is this, in your opinion? Would it be fair to say that the school and the teachers are deficient in meeting your child's needs academically? Why/why not? B: Reasons for tuition 1. Can you offer some reasons why your child is receiving tuition for those subjects (Q2 of A)? For academic reasons: - Is your child academically weak in that subject? To what extent do you think the school and the teachers are responsible for your child's academic progress? Do you think they are doing enough to help your child to improve? If yes, how? If no, why not? What can the school and teachers do in order to change your mind about tuition for your child? For non-academic reasons: - If your child is not academically weak in the subject, why tuition? 51 - If your child makes improvement or progress, would you de-enrol him from tuition? Why, why not? Whose idea was it to have tuition: Yours or your child's? What were the reason/s? 2. Are there any other factors that have influenced your decision to enrol your child at LCs? For example, influence by other parents? C: Choice of tuition centres 1. How did you end up choosing the present LC for your child? - Recommendation by friend? Advertisement? Word of mouth? Name and reputation of LC? 2. Did you have any particular or specific requirements or criteria in your search for a LC? - If no, why not? If yes, what were they? 3. Did any of the following factors (or other factors not mentioned in the list) determine your choice of a LC: - Location Fee Décor Tutors' qualifications, background and race Reputation of the LC Culture of the LC Why, why not? 4. Of all the factors mentioned (and those supplemented by interviewee), which would you say are the 5 most important reasons? - Please explain. 5. How long has your child been enrolled at this present LC? 6. Is this your child's first LC? - If no, what were the reasons for the change? If yes, any intention to change? Why, why not? 52 - Based on Q8 (A), how important a factor is the fee in relation to all the above questions? Other questions 1. Do you live in Hong Kong island, Kowloon, the New Territories, or one of the outlying islands? 2. Do you live in a flat or a house? - How big is the property? Do you own the property in which you live, or do you pay rent? 3. Is your spouse the only breadwinner of the family? 53 APPENDIX E: Interview questions for teachers Teacher's background 1. How many years have you been a teacher? - Is this your first school? If no, how many years have you been with this school? 2. What are the main subjects you teach at the school? - And what level do you teach? Have you always taught these subjects? And how many years have you taught them? 3. Did you choose to teach these subjects, or were you assigned by the school? - Did you have any say in this? Did you express your preference? Why, why not? 4. Are you comfortable teaching these subjects? - Why, why not? 5. Is your first degree related to these subjects? - If not, do you feel or think you are adequately qualified to teach them? Why, why not? 6. Was teaching your first choice of vocation? - If yes, what prompted you to sign up for teaching? If no, what was? And why did you join teaching? 7. Do you see yourself retiring as a teacher? - Or do you think you might change career in the future? If yes, what would it be? 54 Professional development 1. How often does your school conduct professional development for teachers? - Do you think the frequency is enough? Why, why not? What sort of courses are usually offered? How many of these sessions are based on increasing your knowledge of the subject (curriculum) that you teach? 2. What is your opinion of these courses: - Are they very relevant/relevant/irrelevant to you as a teacher? Why, why not? 3. How have these courses impact you as a teacher? 4. If you could improve on/or introduce the selection of courses available, what would you they be? 5. Do you think that the courses arm you adequately to face the challenges from students, in terms of curriculum knowledge and classroom management? - If yes, how? If no, what suggestions would you give to address this? What should be changed? What improvements should be made? What recommendations would you put forward? The school 1. How old is your school? - How would you describe the décor of your school? For example, do you think the building is rundown; needs a facelift; elegant looking, etc? When was the last time the school did any renovation to improve the appearance of the building? 2. If a passerby points to your school building and asks, would you proudly admit that you teach there? Strictly based on the school's appearance. - Why, why not? 3. To what extent do you agree that the aesthetics of a school building affects the morale of the teachers and students? 55 4. Does the school have a dress code for teachers? - What is the dress code for male, female teachers? Does the school enforce this dress code strictly on teachers? 5. What is your opinion of a dress code for teachers? Necessary, unnecessary? Explain. - Do you think schools should enforce dress code on teachers? Explain. The teachers 1. Do you moonlight as a private tutor? - If yes, why? If no, why not? What is preventing you from doing so? Is your marital status one of the reasons? Would you reconsider if the terms (based on participant's answer) are favourable? 2. What do you think of teachers who offer private tuition? 3. Have you ever considered, or toyed with the idea of setting up your own learning centre (LC)? - Why? Why not? 4. If participant replies that the workload prevents them from giving tuition, ask this: - Does the idea of teaching at a LC appeal to you? Why, why not? Some former teachers have quit the profession to start their own LC. Would you? Does the idea appeal to you? If yes, why? What about the difference in income, won't that be a factor? If no, why not? On tuition 1. What is your opinion of LC? Favourable or unfavourable? - Are they necessary? Why, why not? Do you think they actually help improve student's academic performance, or are they simply very good at marketing a false sense of hope? Explain. 2. How would you react if your students say they have private tuition for your subject? - What if your best students have tuition in your subject? 56 - Would you feel you have not done enough to meet your students' needs? Would you blame yourself? 3. Why do you think students engage private tuition? - Can you think of some reasons? Do you agree that tuition is gaining popularity? Why? To what extent are schools or teachers to blame? What can schools or teachers do? 4. For students who are academically weak, what do you think the school or teacher should do to improve their performance? - Do you think it is the school's responsibility, or the teacher's? 5. Some students say that they engage private tuition because teachers are not qualified or have adequate knowledge to teach the subject. What is your response to this? 6. Do you see LCs as complementary or competition to education? 7. Some parents say that if schools offer tuition, they will not engage in outside tuition. Do you agree? - Would you agree to offer tuition as an ECA? Why, why not? 8. In your opinion, do you agree that LCs are gaining popularity with students and parents? - Can you offer your view on this? What reasons can you offer for their popularity? 57 APPENDIX F: Interview questions for students Background information 1. How old are you? - What grade level are you at? 2. Where do you attend school? - How many years have you been there? 3. Is this your first school? - If no, please give a list of schools attended. Reasons for transfer? Do you like your present school? Why, why not? Do you like the curriculum offered by the school? Why, why not? 4. What would you say are your favourite subjects in school? - Do you excel in that subject? Why, why not? 5. Do you like the teachers teaching these subjects? - Why, why not? What do you think of their teaching? Do you find it effective? Why, why not? 6. To what extent does your like or dislike of your teachers affect your performance in that subject? Please explain. The Learning Centre 1. Do you attend additional classes at learning/tutorial centres? - For which subjects do you receive tuition? How long have had tuition for this subject? (Months, years?) Why so early? Or why so late? 58 - Why do you have tuition for this/these subject/s? 2. How often do you have tuition for the subject/s? - How long is each session? Is it a group session or one-to-one session? Reason for your choice? 3. Do you enjoy attending classes at the learning centre? - Why, why not? If participant answers 'yes': Can you be more specific with your answer why you enjoy classes at the centre? Whose decision was it to attend classes at the learning centre? If participant answers 'parents', How do you feel about that? Would you continue or discontinue lessons at the centre? If participant answers 'my decision', Why? 4. Would your academic performance improve, decline or remain the same if you had not enrolled in the learning centre? - Why, why not? 5. How did you come to enrol in this particular centre? 6. Is this your first learning centre? - If yes, what do you like about this centre? If no, how many centres have you tried and what was the reason for your change? Will you be thinking of changing soon? Why, why not? 7. How does this centre compare to your school in terms of the teaching style, environment, location, etc? Other questions 1. Do you live in Hong Kong island, Kowloon, the New Territories, or one of the outlying islands? 2. Where is the location of the learning centre? 3. Would you recommend this learning centre to anyone who asks? - Why, why not? 59 REFERENCES: Albrow, M. (1970). Bureaucracy. London, England: Macmillan & Co Ltd. Becker, G.S. and Becker, G.N. (1997). The Economics of Life. McGraw Hill. Bray, M. and Lykins, C. (2012). Shadow Education: Private Supplementary Tutoring and Its Implications for Policy Makers in Asia. Mandaluyon City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank. Chua, A. (2011). Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. New York, New York: Penguin Press. Ehrenberg, R.G., Brewer, D.J., Gamoran, A. and Willms, J.D. (2001). "Class Size and Student Achievement". In American Psychological Society Vol.2, No.1, May 2001. Available online: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/content/bpl_images/journal_samples/pspi15291006~2~1~003%5C003.pdf Manley, R.J. and Hawkins, R.J. (2010). Designing School Systems For All Students: A Toolbox to Fix America's Schools. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Schlechty, P.C. (2009). Leading for Learning: How to Transform Schools into Learning Organizations. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Schuller, T., Baron S. and Field, J. (2000). "Social Capital: A Review and Critique". In Social Capital: Critical Perspectives. Baron, S., Field, J. and Schuller, T. (eds). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Szreter, S. "Social Capital, the Economy, and Education in Historical Perspective". In Social Capital: Critical Perspectives. Baron, S., Field, J. and Schuller, T. (eds). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 60 Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization/M. Weber; translated from the German by A. M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons ; revised and edited, with an introduction by Talcott Parsons. London : Edinburgh. Publications: The Associated Press The Express Tribune The Standard The New York Times The Straits Times The China Daily 61