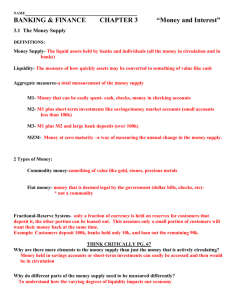

New Sources of Bank Funds: Certificates of Deposit and Debt

advertisement