LESSON 17

advertisement

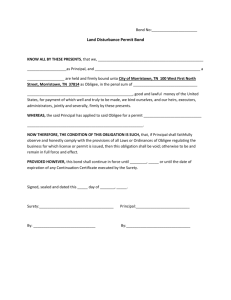

LESSON 9 CONTRACTS Article 1906 of the Louisiana Civil Code says a contract is an agreement by two or more parties where obligations are created, changed or extinguished. An obligation is a legal relationship where a person, the obligor, is bound to render a performance in favor of another, the obligee. That performance could be giving, doing or not doing something. Obligations can arise from contracts and other declarations of will. They can be directly from the law, the management of affairs of another, unjust enrichment or other acts or facts. The main types of obligations a notary will be faced with: Real, heritable, strictly personal, conditional obligations with a term and obligations with multiple persons. Real Obligations are a duty incidental and correlative to a real right. They are incurred as a result of ownership or possession of a thing burdened with a real right. A heritable obligation is when its performance may be enforced by a successor of the obligee or against a successor of the obligor. Basically every obligation is heritable as to all parties, unless the terms or nature of the contract cause it to be otherwise. Heritable obligations are transferable between living persons. The strictly personal obligation arises when its performance can be enforced only by the obligee or only against the obligor. Obligations for personal services are considered strictly personal on the part of the obligor. Also, if the obligation is solely for the benefit of the obligee it is also considered strictly personal. The conditional obligation is dependent on an uncertain event. If the obligation cannot be enforced until the condition occurs, then it is called a suspensive condition. If the obligations may be enforced immediately and will come to an end when the condition occurs, it is called a resolutory condition. The resolutory condition that depends solely on the will of the obligor must be fulfilled in good faith. Conditions are expressed or implied by stipulation, the law, and the nature of the contract or the intent of the parties. There are two things that will make a conditional obligation null; those are: (1) a suspensive condition that is unlawful or impossible (2) a suspensive condition that depends solely on the whim of the obligor Lesson 9 page 1 of 6 An obligation with a term may be express or it may be implied by the nature of the contract. If there is no term, the obligation is due immediately. The term can be certain (fixed) or uncertain (determinable by the intent of the parties or by the occurrence of a future and certain event). In any case, the obligation must be performed within a reasonable time. The obligation with multiple persons may be several, joint or solidary. That is, the obligation binds more than one obligor to one obligee or one obligor to more than one obligee, or more than one obligor to more than one obligee. Let’s take a look at this statement again. The obligation binds: a) more than one obligor to one obligee b) one obligor to more than one obligee c) more than one obligor to more than one obligee. TRANSFERRING OBLIGATIONS Other than by voluntary assignment, an obligation may be transferred from one person to another by assumption or subrogation. The assumption of an obligation still causes the obligor to remain liable for the performance of the obligation. The only way out of this is if the obligee releases the original obligee. An assumption and/or a release must be in writing. The subrogation of an obligation is where one person is substituted for another. Subrogation may be conventional or legal. Conventional subrogation occurs under suretyship contracts (with regard to the payment of claim by an insurer). Any payment or performance that may have been due to the obligee will go directly to the insurer. The subrogation agreement must be in writing. Legal subrogation takes place by the operation of law. If a successor pays estate debts with his own personal funds, the successor is subrogated to the rights of the original creditors and is entitled to recover the amount he paid from the assets of the estate. The new obligee may not recover more than he paid for the estate debts. In order to demand the performance of an obligation, a person must first prove the obligation exists. In the same manner, a person who says an obligation is null or has been changed or extinguished must prove the obligation is null, modified or extinct. Now that we have spelled out what an obligation is and how obligations exist, we can proceed with contracts. CONTRACTS The contract is an agreement between at least two persons. The contract makes, changes or ends an obligation. Familiar to all of us is the contract for sale. In a sale the buyer agrees to buy (one obligation) and the seller agrees to deliver the goods (the second obligation). Lesson 9 page 2 of 6 Contracts fall under Title IV of Book III of the La. Civil Code. Under Title IV contracts are nominate or innominate. Nominate contracts are given a special name, such as a sale, loan, lease or insurance. The nominate contract gives both the obligor and the obligee rights and obligations prescribed by law. The innominate contract does not have a special designation. Everyone is free to contract as long as the object of the contract is legal, possible, determined or determinable. Contracts that derogate from the laws that protect the public are void (null). All contracts must be performed in good faith and may only be dissolved by consent of the parties or by the operation of law. Contracts are heritable and assignable unless the terms of the contract or the law or the nature of the contract precludes those effects. There are seven classes of contracts: (1) Unilateral – party who accepts the obligation of the other does not assume a reciprocal obligation; contains only one promise (2) Bilateral or synallagmatic – when parties obligate themselves reciprocally so the obligation of each party is correlative to the obligation of the other (3) Onerous – each party obtains an advantage in exchange for his obligation (4) Gratuitous – one party obligates himself towards another for the benefit of the other party without receiving anything in return (5) Commutative – performance of the obligation of each party is correlative to the performance of the other (6) Aleatory – performance of either party’s obligations depends on an uncertain event (7) Principal and accessory – made to provide security for the performance of an obligation; ex. suretyship, mortgages, pledges and other security instruments If an obligation results from a contract, that contract is called the principal contract and the obligation only secondary. FOUR REQUIREMENTS FOR CREATING CONTRACTS (1) Capacity – all have capacity to contract; exceptions: unemancipated minors, interdicts, persons deprived of reason at the time of contracting (2) Consent – established through offer and acceptance Consent can be oral, written or implied by action unless the law requires a certain form such as a real estate contract (must be in writing). Consent may be vitiated by error, fraud or duress. Lesson 9 page 3 of 6 (3) Object (certainty) If the object of a contract involves quantities that are undetermined, the contract will still exist if those quantities are determinable at a future date. Quantities of the object may be determined by the parties to the contract or by a court of law. All quantities should be measured in good faith. Note: The succession of a living person may not be the object of a contract with the exception of an antenuptial agreement. This type of succession may not be renounced. (4) Cause is not the same idea as consideration. A person may bind himself to a contract to receive something in return but he may also bind himself for the benefit of another without receiving any thing in return. An obligation cannot exist without lawful cause. Cause is the reason a person would obligate himself in the first place. If the cause is not expressed or the expression of a cause untrue, and a valid cause can be shown, the obligation is still effective. CERTAIN EFFECTS OF CONTRACTS Non-performance of a contract could result in liability for damages or specific performance. ♦ Contracts must be performed in good faith. ♦ The rights and obligations in a contract are both heritable and assignable unless prevented by law, term of the contract or the nature of the contract. ♦ Performance by the obligor ends the contract and that performance can be done by a third party unless the contract calls for a strictly personal performance of the obligor. ♦ Performance must be rendered to the obligee or his authorized representative. NULLITY ♦ A contract is null if the requirements for the creation of a contract are not met. ♦ A contract is absolutely null when it violates the law or a rule of public order. This type of contract may not be confirmed. ♦ A contract is relatively null if it violates a rule intended to protect the parties; i.e. capacity or interdiction. This type of contract may be confirmed and is voidable only by the injured or incompetent party. ♦ An absolutely null contract can be annulled at anytime; i.e. There is no time limit (it does not prescribe). ♦ The annulment of a relatively null contract must be done within five years from the time the grounds for nullity cease (ex. incapacity) or were discovered (an error). ♦ A contract that has been declared null by the court is deemed never to have existed. All parties must be restored to the position they were in prior to the contract. If restoration is impossible, then damages may be awarded by the court. However, the party that knew the contract was null cannot recover anything unless he withdraw from the contract before any performance occurred. Lesson 9 page 4 of 6 ♦ If only a part of a contract is null, it does not nullify the entire contract. ♦ If an onerous contract by a third party results from a null contract, the nullity of the contract does not impair the rights acquired by the third party. DISSOLUTION OF CONTRACTS The following things can dissolve a contract: ♦ A fortuitous event; an event that could not have been forseen at the time of the contract ♦ If the entire performance owed by one party becomes impossible because of a fortuitous event (the other party may recover whatever he has already done) ♦ If only a part of the performance is impossible, the other party may only be required to perform in part as well (in proportion to what the first party was able to accomplish) ♦ If an obligor fails to perform his part of the contract the obligee may regard the contract as dissolved. ♦ A contract may not be dissolved if the majority of the contract has been performed and the remainder of the contract does not substantially impair the interest of the obligee. ♦ A contract can be dissolved if after the non-performing party is served with a notice to perform and he still does not perform his portion of the contract. The dissolution can occur after a reasonable time and the party asking for the performance agrees to dissolve the contract. Failure of the non-performing party to complete his obligation to the contract results in placing the obligor in default. ♦ If the delayed performance by the obligor causes the benefit to the obligee to be of no value, the obligee may regard the contract as dissolved. ♦ If both parties agree to dissolve the contract then the dissolution is allowed. ♦ Dissolution of a contract requires that all parties are to be returned to their original positions as though the contract never existed. If this is not possible, then damages may be awarded by the court. ♦ If a contract does not have a termination date, it may be terminated at the will of either party by giving notice to the other party. RULES OF INTERPRETATION OF A CONTRACT ♦ Interpreting a contract depends on the intent of the parties. ♦ When the contract is clear and explicit no further questioning of the parties is necessary. ♦ Words in a contract are given their general, common meanings. Technical words must be given their technical meanings. ♦ If words in a contract have several meanings, the object of the contract will decide the best choice. Lesson 9 page 5 of 6 ♦ Provisions in a contract will be interpreted with a meaning that renders the contract effective and with regard for other provisions in the contract. ♦ Interpretation of a contract must not restrict the scope of the contract. For example, if the parties include a specific example in the contract to eliminate any doubt of what they intend to happen, attention should not be limited to the specific example alone. ♦ When contractual parties do not make provisions for a particular situation that resulted from their performance of the contract, the law will interpret the contract according to their express provision in the contract and according to any implied results that would normally occur do to their performance. ♦ The equity of a contract is based on the principal that no one is allowed to take unfair advantage of another. ♦ The usage of a contract is interpreted by comparing other contracts of the same objective to determine the meaning and intention of the parties. ♦ In case of doubt, the form of the contract will cause the interpretation of the contract to be against the party who created it. ♦ In the case where a doubt cannot be resolved, the contract must be interpreted against the obligee and in favor of the obligor. VOCABULARY Contract - an agreement by two or more parties whereby obligations are created, modified, or extinguished Obligor - the person who is bound by contract to render performance in favor of another Obligee - the person to whom a performance is due (because of a contract) from another Heritable - transferable; capable of transferring by voluntary action or succession; not strictly personal Vitiated - to make ineffective; invalidate Solidary - existing jointly and severally; being a party to a solidary obligation (when one obligor owes an indivisible performance to distinct obligees, the obligees are solidary obligees) Real Right - a right that is attached to a thing rather than a person Lesson 9 page 6 of 6