View/Open - YorkSpace

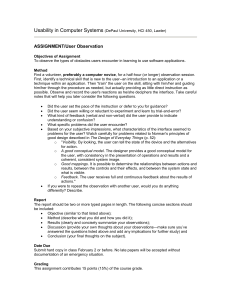

advertisement