CIVILIAN EVACUATION TO DEVON IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

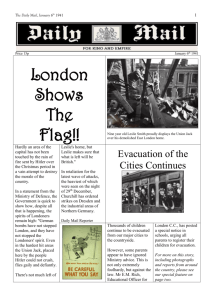

advertisement