Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect - AFL-CIO

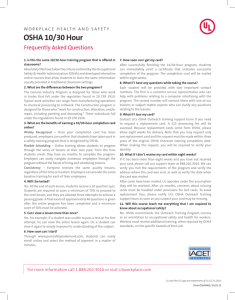

advertisement