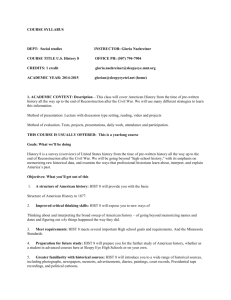

Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution

advertisement

Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution

Author(s): Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson

Source: The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Feb., 1992), pp. 24-50

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Economic History Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2598327 .

Accessed: 28/05/2014 10:42

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Wiley and Economic History Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Economic History Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EconomicHistoryReview, XLV,

I(I992),

pp.

24-50

Rehabilitating

theindustrial

revolution'

By MAXINE BERG and PAT HUDSON

T he historiography

of the industrial

revolution

in Englandhas moved

and earlynineteenth

centuries

as

awayfromviewingthelateeighteenth

a uniqueturning

The notionof

pointin economicand socialdevelopment.2

radicalchangein industry

and societyoccurring

overa specific

periodwas

in the I920s and I930s by Claphamand otherswho

effectively

challenged

stressedthe long taprootsof development

and the incomplete

natureof

economicand socialtransformation.'

Afterthisit was no longerpossibleto

claimthatindustrial

societyemergedde novoat anytimebetweenc. I750

and i85o, buttheidea ofindustrial

revolution

survived

intothe i960s and

I970s. In i968 Hobsbawmcould state unequivocally

that the British

revolution

wasthemostfundamental

in thehistory

industrial

transformation

in written

oftheworldrecorded

documents.4

Rostow'sworkwasstillwidely

of whatwas seen as a new typeof class

influential

and the socialhistory

to be written.

The idea thatthelate eighteenth

societywas onlystarting

and early nineteenth

centurieswitnesseda significant

socioeconomic

remained

wellentrenched.'

discontinuity

In thelastdecadethegradualist

has appearedto triumph.

In

perspective

economichistoryit has done so largelybecauseof a preoccupation

with

at theexpenseofmorebroadlybasedconceptualizations

growth

accounting

havebeenproducedwhichillustrate

ofeconomicchange.New statistics

the

slowgrowthofindustrial

outputand grossdomesticproduct.Productivity

andinvestment

grewslowly;fixedcapitalproportions,

savings,

changedonly

emained

workers'

andtheirpersonal

gradually;

livingstandards

consumption

I Some of the argumentsin this articleappear in Berg, 'Revisionsand revolutions';and in Hudson,

We are verygrateful

to N. F. R. Craftsfordetaileddiscussionofthesubstance

ed., Regionsand industries.

of an earlierversion,and to seminargroupsat theInstituteof HistoricalResearch,London, theNorthern

Economic HistoriansGroup, Universityof Manchester,the Universityof Glasgow, the Universityof

Paris viii at St Denis, and the Universitiesof Oslo and Bergen.Althoughmanyof the argumentsin the

paper apply as much to Scotlandand Wales as to England, we confinediscussionin thispaper to the

industrialrevolutionin England in orderto avoid confusionwherethe existingliteratureis discussed.

2 For a broad surveyof this and othertrendsin the historiography

of the industrialrevolutionsee

Cannadine,'The past and the present'.

thetrendawayfrommorecataclysmic

interpretations

3Clapham is mostoftenassociatedwithinitiating

in Economichistory

of modern

Britain,but the shiftin emphasisis obviousin otherworksof the interwar

Heaton, 'Industrialrevolution';Redford,

period and earlier,e.g. Mantoux, The industrialrevolution;

revolutions;

George,Englandin transition.

Economichistory

ofEngland;Knowles,Industrialand commercial

4 Hobsbawm, Industry

and empire,p. I3.

class identifiedthe industrialrevolutionperiod as

5Thompson in his Making of theEnglishworking

growth,thoughchallengedover

the greatturningpoint in class formation.Rostow's Stages of economic

the precisefitbetweenthe model and Britishexperience,was a powerfulvoice in favourof significant

Landes in UnboundPrometheus

drew a convincingpicture

and unprecedentedeconomicdiscontinuity.

of the transformations

initiatedby technicalinnovation.

24

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

25

largely unaffectedbefore I 830 and were certainlynot squeezed. The

macroeconomicindicatorsof industrialand social transformation

were not

presentand so the notionof industrialrevolutionhas been dethronedalmost

entirely

leavinginsteadonlya longprocessofstructural

changein employment

fromagrarianto non-agrarian

occupations.6

At the same time,and oftentakinga stronglead fromthe gradualismof

economichistoryinterpretations,

the social historyof the periodhas shifted

away fromanalysisof new class formations

and consciousness.7The postMarxian perspectivestressesthe continuitybetweeneighteenthand ninesocial protestand radicalism.Chartism,forexample,is seen

teenth-century

as a chronologicalextensionof the eighteenth-century

constitutional

attack

on Old Corruption.8

Late eighteenth-century

depressionsand theNapoleonic

of social tensionswhichare viewed

Wars are seen as the majorprecipitators

and selectiveeconomichardshipratherthanfrom

as arisingfromtemporary

anynewradicalcritiqueor alternative

politicaleconomy.9'The ancienregime

oftheconfessional

state'survivedtheeighteenth

and earlynineteenth

centuries

substantiallyunchanged.'0 In demography,the dominantexplanationof

the late eighteenth-century

populationexplosionstressesits continuity

with

a much earlier-established

demographicregimewhichremainedintactuntil

at least the I840s.11 And an influentialtendencyin the socio-cultural

of the last few yearshas argued that the English industrial

historiography

revolutionwas veryincomplete(if it existedat all) because the industrial

bourgeoisiefailedto gainpoliticaland economicascendancy.'2Thus England

neverexperienceda periodofcommitment

to industrialgrowth:theindustrial

in a great arch of continuitywhose

revolutionwas a brief interruption

economic and politicalbase remainedfirmlyin the hands of the landed

in metropolitan

and its offshoots

finance.Gentlemanly

aristocracy

capitalism

in the

prevailedand the power and influenceof industryand industrialists

Englisheconomyand societywere ephemeraland limited.'3

6 Crafts,Britisheconomic

growth.See also Harley, 'Britishindustrialization';

McCloskey,'Industrial

revolution';Feinstein,'Capital formationin GreatBritain';Lindertand Williamson,'English workers'

livingstandards'.More radical social and culturalchange is implied in some of the recentliterature

discussingincreasesin internalconsumption.See Brewer,McKendrick,and Plumb, Birthof consumer

But we concentrate

society.

hereon thegradualismof supplyside approachesin economichistorybecause

supplyside changesare vitalin underpinning

any changein aggregatedemand. The so-calledconsumer

revolutionof these years can only be understoodas part of a dynamicinterplaybetweenchanging

consumptionpatternsand the transformation

of employmentand production.

7 Characterized

by Thompson,Makingof theEnglishworking

class, and emphasizedby Foster,Class

struggle.

Chartism'.

8 StedmanJones,'Rethinking

9 Williams, 'Morals'; Stevenson,Popular disturbances,

pp. ii8, I52; Thomis, Luddites,ch. 2. For

and Randall, 'Comment';Randall, 'Philosophyof Luddism'.

critiquesof thisliteraturesee Charlesworth

For a balanced surveyof the debate on the 'moraleconomy',see Stevenson,'Moral economy'.

10The phraseis fromClark,Englishsocietywhichis heavilycriticalof the social historyof the I970S

and i98os. For a critiqueof his position,see Innes, 'JonathanClark'.

11 Wrigleyand Schofield,Populationhistory.

The argumentis summarizedin Wrigley,'Growthof

population'and in Smith,'Fertilityand economy'.

12 See Wiener, English culture;Anderson,'Figures of descent'; Cain and Hopkins, 'Gentlemanly

capitalism';Ingham,Capitalismdivided?;Leys, 'Formationof Britishcapital'. For the argumentthatthe

landed aristocracy

was an eliteclosed to new wealthsee Stone and Stone,Open elite?;Rubinstein,'New

men'.

13 Ibid. The term'great arch' is fromCorriganand Sayer, The greatarch althoughthis work itself

does not place exclusivestresson continuity.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26

MAXINE BERG

and PAT HUDSON

Though currentconsensus stronglyfavourscontinuityand gradualism,

contemporariesappear to have had littledoubt about the magnitudeand

industrialchange. In i8I4

importanceof changein the period,particularly

PatrickColquhoun wrote:

in GreatBritain

the progressof manufactures

It is impossibleto contemplate

Its rapidity,

withinthe last thirtyyearswithoutwonderand astonishment.

war,exceeds

of theFrenchrevolutionary

sincethecommencement

particularly

The improvement

of steamengines,but aboveall thefacilities

all credibility.

by

to the greatbranchesof the woollenand cottonmanufactories

afforded

bycapitaland skill,arebeyondall calculation

machinery,

invigorated

ingenious

applicableto silk,linen,hosieryand various

. . . thesemachinesare rendered

otherbranches.14

RobertOwen in i820 identifieda key turningpoint:

GreatBritain,

in particular,

It is wellknownthat,duringthelasthalfcentury

increaseditspowersof production,

beyondanyothernation,has progressively

introduced

in scientific

and arrangements,

improvements

by rapidadvancement

of productive

moreor less, intoall the departments

throughout

the

industry

15

empire.

And in i833 Peter Gaskellwroteof the social and politicalrepercussionsof

formingan imperiumum

economicchange,seeingworking-class

organizations

in imperio"of the mostobnoxiousdescription'.'6In i85I the OweniteJames

Hole wrotethat:

havemenbecometo pursue

Class standsopposedto class,and so accustomed

of thatof others,thatit

theirownisolatedinterests

apartfromand regardless

has becomean acknowledged

maxim,thatwhena manpursueshisowninterest

every

alonehe is mostbenefitting

society-amaxim. . . whichwouldjustify

crime'and folly.... The principleof supplyand demandhas been extended

but less

to men.These haveobtainedthereby

moreliberty,

fromcommodities

withthethraldom

ofFeudalismtheyhavetaken

bread.Theyfindthatin parting

in fact.17

has ceasedin namebutsurvived

on thatof Capital;thatslavery

but it has been obscured

Radical change was obvious to contemporaries

in particularhas been

in recenthistoriography,

and industrialperformance

traditionalpast. We argue here

viewed as an extensionof a pre-industrial

The nationalaccounts

thatthe industrialrevolutionshouldbe rehabilitated.

approach to economic growth and productivitychange is not a good

The

startingpoint forthe analysisof fundamentaleconomicdiscontinuity.

errorsof

measurementof growthusing thisapproachis proneto significant

estimationwhich arise fromthe restricteddefinitionof economicactivity,

fromthe incompletenature of the available data, and fromassumptions

embodiedin the analysis.We arguethatgrowthand productivity

changein

we

underestimated.

the period are currently

But, much more importantly,

stressthatgrowthrateson theirown are inadequateto thetaskofidentifying

and comprehendingthe industrial revolution. The current orthodoxy

14

15

16

17

Colquhoun, Treatiseon wealth,p. 68.

Owen, Reportto thecountyof Lanark, pp. 246-7.

populationof England,pp. 6-7.

Gaskell,Manufacturing

Hole, J., Lectureson social science,quoted in Briggs,Victoriancities,p. I40.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

27

underplayseconomicand social transformation

because such developmentis

not amenable to studywithinthe frameof referenceof nationalaccounts

and aggregatestatistics.We examinefourareas in whichfundamentaland

unique change occurred during the industrialrevolution:technical and

organizational

innovationoutsidethefactory

sector,thedeployment

offemale

and childlabour,regionalspecialization,and demographicdevelopment.For

each area we identifyboth problems of underestimationand of the

measurementof fundamentalchange. We conclude by consideringthe

importanceforsocial and politicalhistoryof our reassessmentof the extent

in theseyears.

and natureof transformation

Unlike the earliernationalaccountsestimatesof Deane and Cole, recent

calculationsshow veryslow growthratesbeforethe i83os and particularly

in the last fourdecades of the eighteenth

century.Explanationsforthisslow

growthvaryconsiderablybut the workof Craftshas been the most widely

influentialin currentassumptionsabout the industrialrevolution.'8Crafts

calculatedthatchangein investment

proportionswas verygradualuntilthe

early nineteenthcentury and that total factor productivitygrowth in

was onlyaround0.2 per cent per annumbetweenI760 and

manufacturing

i8oi and 0.4 per centbetweeni8oi and i83I. Even totalfactorproductivity

growthacross the entire economy, inflatedin Crafts's opinion by the

of agriculture,

performance

grewveryslowly:0.2 per centper annum I760i8oi, 0.7 per cent i80i-3I, reachingi.o per cent onlyin the period I83II86o.19

Severalpointsabout thesegrowthratescould be made. Perhapsthe most

importantis that,althoughproductivity

growthappearsgradual,it was high

enoughto sustaina muchincreasedpopulationwhichunderearliereconomic

would have perished.Crafts,however,chooses to emphasize

circumstances

the poor showingof manufacturing,

arguingthat one small and atypical

in

which

accelerated

sector,cotton,

growth

sharply,accountedforas much

in

It was a modernsector

as half of all productivity

gains manufacturing.

overallimpact.

floatingin a sea of tradition,too small to have a significant

For mostof industry,he concluded,'not onlywas the triumphof ingenuity

slow to come to fruitionbut it does not seem appropriateto regard

innovativenessas pervasive'.20 We believe that this opinion rests on two

false assumptions.First, it is assumed that the innovativefactorysector

functionedindependently

of, and owed littleto, changesin the restof the

and service economy. Secondly,innovationis assumed to

manufacturing

18.

Deane and Cole, Britisheconomicgrowth;Crafts,Britisheconomicgrowth;Williamson,'Why was

Britisheconomicgrowthso slow?'; McCloskey,'The industrialrevolution'.WhereasCraftsstressesthe

Williamson

opportunities,

oftheeconomybecauseofa shortageofhighreturninvestment

lowproductivity

arguesthatthe industrialrevolutionwas crowdedout by theeffectofwar debtson civilianaccumulation.

For recentdebatebetweenthesetwoviewssee Crafts,'Britisheconomicgrowth';Williamson,'Debating';

Mokyr,'Has theindustrialrevolutionbeen crowdedout?'. See also Williamson,'Englishfactormarkets';

Heim and Morowski,'Interestrates'.

19 Crafts,Britisheconomic

growth,pp. 3I, 8i, 84.

20 Ibid., p. 87.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28

MAXINE BERG

and PAT HUDSON

ofcapital-intensive

plantand equipmentwhich

concernonlytheintroduction

has an immediatemeasurableimpact on productivity.

We returnto these

below but first

importantpointsabout economicdualism and productivity

brieflydeal withmeasurementproblemsof the nationalaccountsapproach

toundermine

periodwhichalonearesufficient

duringtheindustrialrevolution

confidencein the currentgradualistorthodoxy.

II

Industrialoutput and GDP are aggregateestimatesderived from the

weightedaverages of theircomponentswhich, as Craftshimselfadmits,

of assigning

involves 'a classic index numberproblem'.2' The difficulties

weightsto industrialand othersectorsof the economy,allowingforchanges

in weightsover time and for the effectsof differential

price changes and

value-addedchangesin thefinalproduct,are insurmountable

and willalways

involvewide marginsof potentialerror.Errorsin turnbecomemagnifiedin

residualcalculationslike thatof productivity

growth.22

At the root of problemsconcerningthe compositionof the economyby

sector in the national accounting frameworkare the new social and

occupationaltablesof Lindertand Williamsonupon whichCraftsand others

rely.23These give a higherprofileto the industrialsectorthan the earlier

social structureestimatesof King, Massie, and Colquhounand fitwell with

But the latitude

currentworkon the importanceof proto-industrialization.

for potentialerrorin these tables is great. Lindert himselfhas cautioned

that for the large occupational groupingsof industry,agriculture,and

commerceerrormarginscould be as highas 6o per centwhileestimatesfor

shoemakers,carpenters,and othersare 'littlemorethanguesses'.24Lindert

and Williamsonrelyon theburialrecordsofadultmalesas theirmainsource

of occupationalinformation.Yet women and childrenwere a vital and

workforceduringthe proto-industrial

growingpillar of the manufacturing

of allowingfordual and

difficulties

and earlyindustrialperiods.The further

of

with

and

dealing

descriptionslike 'labourer',which

tripleoccupations,

give no indicationof sector,suggestthatno reliablesectoralbreakdownfor

labourinputscan be made. Beforethe 1831 census,and withoutthe benefit

of much more research,not only are sectoraldistributionslikely to be

erroneous,but they are particularlylikely to underestimatethe role of

growingsections of the labour force and of the vitallyimportant,often

innovative,overlapsbetweenagrarianand industrialoccupations.

Nor are the industrialmacrodataparticularlyrobust. Many of Crafts's

derivedfrom

estimatesof sectoroutputsand inputsrelyon usingmultipliers

a handfulof examplesand only a sample of industriesis used. This omits

21 Ibid., p. I7.

22

Jackson,'Governmentexpenditure';Mokyr, 'Has the industrialrevolutionbeen crowded out?',

p. 306.

Lindertand Williamson,'RevisingEngland's social tables'; Lindert,'English occupations'.

fromrural

ruralnon-agricultural

Ibid., p. 70I; Wrigleyalso uses theseestimates,and distinguishes

of estimatesforagricultural

agriculturalpopulation.Note, however,that he emphasizesthe fallibility

populationbeforei8oo. See Wrigley,'Urban growthand agriculturalchange',p. i69.

23

24

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

29

increasein the economy:

potentially

vitalsourcesof outputand productivity

for example, food processing,metal wares, distilling,lead, furniture,

The

coachmaking,and new industrieslike chemicals and engineering.25

of industryas a whole

sectorswhichare includedshould be representative

but in fact the sample is heavilybiased in favourof finishedratherthan

goods. Changein thenatureand uses ofrawand semi-processed

intermediate

materialinputsprobablyresultsin bias because majorsourcesof innovation

in the economyare neglected.26

In attemptingto measure the size and natureof the servicesectorthe

encountersa virtuallyimpossibletask. Crafts

macro accountingframework

in the servicesector

is forcedto relyon the assumptionthatproductivity

increased no more than in industry.Behind this lies the even more

problematicassumptionthatthe servicesectorexpandedat the same rateas

in line withwhatlittlewe knowabout

populationbeforei8oi and thereafter

rents, (central) governmentexpenditure,and the growth of the legal

of the servicesectorexcludesdirectevidence

profession.Crafts'streatment

of what was happeningin transport,financialservices,retailand wholesale

trades,professionsotherthanthe law (iinotherwords,whatwas happening

to transactions

costs), to say nothingof personaland leisureservices.27And

furthercontroversysurroundsCrafts's estimatesof agriculturaloutput

because he relies on inferencesfromquestionableestimatesof population

growth,agriculturalincomes,prices,and incomeelasticities.28

Large areas of economicactivityhave of courseleftno availablesourceof

quantitativedata at all. Even in the twentiethcenturynational income

accounting,whenused as an indicatorofnationaleconomicactivity,involves

but these are magnifiedin earlier

major problems of underestimation,

applicationsbecause so mucheconomicactivitywas embeddedin unquantifiThe problemsofthenational

able and unrecordednon-market

relationships.29

for periods of fundamental

are

further

compounded

approach

accounting

economicchangebecause the proportionof totalindustrialand commercial

activityshowingup in the estimatesis likelyto changeradicallyover time.

If, as seems likely,entrythresholdsin mostindustrieswere low, industrial

expansionmighttake place firstand foremostamong a myriadsmall firms

is lost to historianswho

whichhave leftfewrecordsand whosecontribution

confinethemselvesto easily available indices. Finally, price data for the

growth,pp. I7-27; Hoppit, 'Counting',p. i82.

Crafts,Britisheconomic

chs. II, I2; Rowlands, Mastersand men;

Hudson, Genesis,ch. 6; Berg, Age of manufactures,

Sigsworth,Black DykeMills, ch. I.

27

expenditure';

Hoppit, 'Counting',pp. I82-3; Price,'Whatdo merchantsdo?'; Jackson,'Government

idem,'Structureof pay'.

28

Crafts,Britisheconomicgrowth,pp. 38-44; Mokyr, 'Has the industrialrevolutionbeen crowded

out?'.,pp. 305-I2; Jackson,'Growthand deceleration';Hoppit, 'Counting',p. i83. Crafts,however,was

certainenoughof theseand of his otherestimatesto writein i989 'The dimensionsof economicchange

in Britainduringthe IndustrialRevolutionare now reliablymeasured.A numberof features. . . are

research';Crafts,'Britishindustrialization

likelyto be subjectto onlyminorrevisionas a resultof further

context',p. 4i6.

in an international

pp. 27-36;

29 For discussionsof the problemsof nationalincomeaccountingsee Hawke, Economics,

of growth,passim. For discussionof the embeddednessof economicactivitysee

Usher, Measurement

Polanyi, ed., Trade and market,pp. 239-306; Douglas and Isherwood, World of goods; Beneria,

'Conceptualisingthe labour force'.

25

26

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

30

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

eighteenthcenturyare sparse and highlypartial. This creates a problem

because the nationalaccountsframework

across

requiresprice information

the board to calculatevalue added in each sector.

These considerations

togetherprecludedrawingfirmconclusionsfromthe

availableand suggestthatthe bias theycontainis likely

estimatescurrently

of productionand productivity

in the secondary

to resultin underestimation

and tertiarysectorsof the economy.

In thisconnectionit is worthnotingthatCrafts'srecentstatisticalanalysis

of industrialoutput series for Britain,Italy, Hungary,Germany,France,

Russia, and AustriashowsthatBritainand Hungarywerethe onlycountries

to exhibita prolongedperiodof increaseof trendrateofgrowthin industrial

In the light of the

productionduring the process of industrialization.30

qualitativeevidence of the extentand speed of change in Germanyand

Russia in particular,this findingsuggestseitherthat the macro estimates

are farfromaccurateand/orthatpayingundue attentionto changesin the

trendratesof growthat the nationallevel is not a helpfulstartingpointfor

or understanding

economictransformation.

identifying

III

in

Aggregativestudiesare dogged by an inbuiltproblemof identification

posingquestionsabout the existenceof an industrialrevolution.As Mokyr

has pointedout in the Englishcase:

whichgrewslowlyweremechanising

and switching

to factories

Someindustries

likesoapandcandles)whileconstruction

(e.g.paperafteri 8oi, woolandchemicals

ruledsupreme

withfewexceptions

and coal miningin whichmanualtechniques

untildeepin thenineteenth

rates.31

century,

grewat respectable

Clearlytechnicalprogressis notgrowthand rapidgrowthdoes noteverywhere

of productionfunctions.Can we justifyusing

imply the revolutionizing

manufacturing

high aggregateinvestmentratios, high factorproductivity

techniques,and theirimmediateinfluenceon the formalGDP indicatorsas

In answeringthis

our yardstickof industrialinnovationand transformation?

question, we need to look more closely at the model of industrialization

whichunderpinsmuch currentanalysis.

of the industrialrevolutionrelyon an analytical

The new interpretations

divide between the traditionaland modern sectors: mechanized factory

withhighproductivity

on theone hand,and a widespreadtraditional

industry

industrialand servicesectorbackwateron the other. It is argued that the

large size of the traditionalsector, combined with primitivetechnology,

made it a drag on productivity

growthin the economyas a whole.32But it

is notclearhowhelpfulthisdivideis in understanding

theeconomicstructure

30

This analysisemploysthe Kalman filterto eliminatethe problemof false periodizationand to

distinguishbetweentrendchangesand the effectof cyclesof activity.See Crafts,Leybourne,and Mills,

'Britain'; idem,'Trends and cycles'.

31 Mokyr,'Has the industrialrevolution

been crowdedout?', p. 3I4.

32

pp. 5-6; Crafts,

revolution,

growth,

ch. 2; Mokyr,Economicsof theindustrial

Crafts,Britisheconomic

'Britishindustrialization'.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

3I

and earlynineteenth-century

England.33In

or the dynamismof eighteenthreality,it is impossibleto make clear-cutdivisionsbetweenthe traditional

and the modern as there were rarely separate organizationalforms,

technologies,locations,or firmsto be ascribedto either.Eighteenth-and

cottonmanufacturers,

servingdomesticas well as foreign

nineteenth-century

spinningin factorieswithlargemarkets,typicallycombinedsteam-powered

scale employmentof domestichandloomweaversand oftenkept a mix of

powered and domestichand weaving long afterthe powered technology

becameavailable.This patternwas a functionofriskspreading,theproblems

of earlytechnology,and the cheap labour supplyof womenand childrenin

Thus fordecades the 'modern'sectorwas actuallybolsteredby,

particular.34

and derivedfromthe 'traditional'sector,and not the reverse.

Artisans in the metal-workingsectors of Birminghamand Sheffield

frequentlycombinedoccupationsor changedthem over theirlife cycle in

such a way that they too could be classifiedin both the traditionaland

modern sectors.35Artisan woollen workersin West Yorkshireclubbed

togetherto build millsforcertainprocessesand thushad a footin both the

modernand traditionalcamps. These so-called'companymills'underpinned

Thus the traditionaland the modern

the success of the artisanstructure.36

were most often inseparable and mutuallyreinforcing.Firms primarily

diversified

into metal processingventuresas

concernedwith metalworking

a way of generatingsteadyraw materialsupplies. This and othercases of

verticalintegration

providemore examplesof the tail of 'tradition'wagging

the dog of 'modernity'.37

The non-factory,

supposedlystagnantsector,oftenworkingprimarilyfor

domesticmarkets,pioneeredextensiveand radicaltechnicaland organizational

change not recognizedby the revisionists.The classic textileinnovations

were all developed withina rural and artisanindustry;the artisanmetal

handprocesses,handtools,and newmalleable

tradesdevelopedskill-intensive

alloys. The wool textile sector moved to new products which reduced

finishingtimes and revolutionizedmarketing.New formsof putting-out,

wholesaling,retailing,creditand debt,and artisanco-operationweredevised

in the face of the new

as ways of retainingthe essentialsof older structures

morecompetitiveand innovativeenvironment.

Customarypracticesevolved

to matchtheneeds ofdynamicand market-orientated

production.The result

33 The use of a two-sector

of development

modelofindustrialchangeis reminiscent

traditional/modern

economics during the I950s and i96os which looked to a policy of accelerated and large-scale

throughpromotionof the modernsectoras a spearheadforthe restof the economy.

industrialization

of thediverseand dependentlinkagesbetween

This divisionwas abandonedin the I970S withrecognition

the 'formal'and 'informal'and betweenthe 'traditional'and 'modern'sectors,yetit has gainedrenewed

prominencein economichistory.See Moser, 'Informalsector',p. I052; Toye, Dilemmasin development.

For fullerdiscussionof parallelideas in developmenteconomics,see Berg, 'Revisionsand revolutions',

of the dynamismof the smallfirmsectorsee Sabel and Zeitlin,

pp. 5i-6. For a particularinterpretation

'Historicalalternatives',pp. I42-56; also Berg, 'On the origins'.

34 See, forexample, Lyons, 'Lancashirecottonindustry'.

35 Berg, 'Revisions and revolutions',pp. 56, 59; idem,Age of manufactures,

chs. II I2; Sabel and

Zeitlin, 'Historical alternatives',pp. I46-50; Lyons, 'Vertical integration';Berg, 'Commerce and

creativity',

pp. I90-5.

capital,pp. 70-80; idem,'From manorto mill'.

Hudson, Genesisof industrial

Wadsworthand Mann, Cottontrade; Hamilton,

woollenand worstedindustry;

Heaton, Yorkshire

of southWales.

John,Industrialdevelopment

Englishbrassand copperindustries;

36

37

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

was considerabletransformation

even withinthe framework

of the so-called

traditionalsector.

The revisionists

arguethatmostindustriallabourwas to be foundin those

occupations which experiencedlittle change.38But the food and drink

trades,shoemaking,tailoring,blacksmithing,

and tradescateringforluxury

consumptionsuccessfullyexpanded and adapted to provide the essential

urbanserviceson whichtownlife,and hence much of centralizedindustry,

was dependent.Furthermore,

earlyindustrialcapitalformation

and enterprise

typicallycombinedactivityin the food and drinkor agricultural

processing

tradeswithmoreobviouslyindustrialactivities,

creatinginnumerable

external

economies.39This was true in metal manufacturein Birminghamand

Sheffieldwhereinnkeepersand victuallerswere commonlymortgageesand

In the south Lancashiretool

joint ownersof metal workingenterprises.40

tradesPeter Stubs was not untypicalwhen he firstappeared in I788 as a

tenantof the WhiteBear Inn in Warrington.Here he combinedthe activity

of innkeeper,maltster,and brewerwiththatof filemakerusing the carbon

in barm bottoms(barrel dregs) to strengthen

the files.41There are many

and industry.

examplesof thiskind of overlapbetweenservices,agriculture,

These were the norm in business practiceat a time when entrepreneurs'

to spreadthroughdiversification

of portfoliosand where

riskswere difficult

so much could be gained fromthe externaleconomiescreated by these

overlaps.

We do not suggesthere thatproductivity

growthat the rate experienced

in cottontextileswas achievedelsewhere,but thatthe successof cottonand

othermajorexportswas intimately

relatedto and dependentuponinnovations

in otherbranchesof the primary,secondary,

and radical transformations

and tertiary

sectors.Dividingoffthe modernfromthe traditionalsectorsis

an analyticaldevice which hides more than it reveals in attemptingto

understandthe dynamicsof changein the industrialrevolution.

IV

More questionablethan theirassumptionof the separatenessand dependence of the traditionalsectoris the revisionists'evaluationof productivity

of the

changein the economyat this time. Throughoutthe historiography

measureshave seldombeen clearlydefined,

industrialrevolutionproductivity

thelimitations

ofmeasureshave rarelybeen explained,and figuresoflimited

have been produced and widely accepted on trust. Total

meaningfulness

factorproductivity

(TFP) is the measuremost used by Craftsand others

was slow to growin

and its use has led themto concludethatproductivity

the period. TFP is usuallycalculatedas a residualafterthe rate of growth

of factorinputshas been subtractedfromthe rate of growthof GDP.

38 Crafts,

p. 69; Wrigley,People,citiesand wealth,pp. I33-57; idem,Continuity,

Britisheconomic

growth,

chanceand change,p. 84.

39 Jones,'Environment';

Burley,'Essex clothier';Chapman,'Industrialcapital'; Mathias,'Agriculture

and brewing'.

40

p. i83.

Berg, 'Commerceand creativity',

pp. 4-5.

industrialist,

41 Ashton,Eighteenth

century

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

33

There are severalmajor problemswiththe TFP measure.First,TFP as

a residualcalculationis heavilyaffectedby any mistakesin the estimation

of sectoraloutputsand factorinputs.If the originalsectorweightingswere

wrong,TFP estimatesmaybe highlydistorted.Big differences

in TFP may

also arise fromvariationsin the estimatedgrowthof GDP. Secondly,if

factorreallocationfromsectorswith low marginalproductivities

to those

withhighones was an important

featureof theperiod,it will notbe possible

to derive reliable economy-widerates of TFP growthsimplyby takinga

weightedaverageacross sectors.The effectsof factorreallocationmust be

incorporated.42

Thirdly,TFP embodiesa numberof restrictive

assumptions

rarelyacknowledgedby those who use the measure. These are perfect

mobilityof factors,perfectcompetition,

neutraltechnicalprogress,constant

returnsto scale, and parametricprices.43The eighteenth-century

economy

did not matchthese assumptions.For example,the assumptionof neutral

technicalprogressis suspect in view of the evidenceof long-termlaboursavingtechnicalchange. So too are assumptionsof constantreturnsto scale

when set against evidence of increasingreturns;TFP calculationsshould

allow forimperfect

competitionand changingelasticitiesof productdemand

and factorinputs.44Assumptionsof fullemploymentof labour and capital

and of perfectmobilityare also inappropriate.Movementof populationwas

often not a response to shortagesof labour in industry;indeed many

industrialsectors came to be characterizedby flooded labour markets,

particularlyfor the less skilled tasks. These were paralleled by massive

immobilepools ofagricultural

labourin manysouthernand midlandcounties.

was endemicand chronicunder-utilization

Structuralunemployment

of both

labour and capitalwas aggravatedby seasonal and cyclicalswings.45

TFP takesno accountofinnovationin thenatureofoutputs

Furthermore,

or of changein the qualityof inputs,yetwe know thatboth were marked

featuresof the period. On the input side, labour needs to be adjusted in

TFP calculationsforchangesin age, sex, education,skill, and intensityof

work. Output per workeris also affectedby changesin the relativepower

of employersto extractwork effortand in the power of employeesto

withholdit.46Similarly,materialinputswerechangingconstantly

as product

innovationaffectedthe natureof raw materialsand intermediate

goods as

wellas finalproducts.The smallmetaltradeswerea case in point:innovation

entailednot poweredmechanizationbut the introductionof niewproducts

and the substitutionof cheap alloys forpreciousmetalsas raw material.47

42

Williamson,'Debating', p.

270;

Mokyr,'Has theindustrialrevolutionbeen crowdedout?', pp.

I2.

305-

Link, Technological

change,pp. I5-20.

Eichengreen,'What have we learned?',pp. 29-30; Link, Technological

change,p. I4. For discussion

ch. 6; David,

of evidenceof labour-savingtechnicalchange,see Rosenberg,Perspectives

on technology,

Technicalchoice,ch. I; Field, 'Land abundance,interest/profit

rates',p. 4I I; Stoneman,Economicanalysis

oftechnological

change,pp. I 56-67.For evidenceand discussionofincreasingreturns,see David, Technical

choice,chs. 2, 6.

45 Eichengreen,'Causes of Britishbusinesscycles'; Allen, Enclosure,

ch. I2; Hunt, 'Industrialisation

and regionalinequality'.

46 Link, Technological

change,p. 24; Eichengreen,'What have we learned?',pp. 29-30; Elbaum and

Lazonick, Declineof theBritisheconomy,

pp. I-I7; Lazonick, 'Social organisation',p. 74.

47 Berg,Age of manufactures,

chs. II, I2; Rowlands,Mastersand men.

43

44

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

in consumption

patternsand habits.48

Productinnovationfuelleda revolution

But because the nationalaccountsframeworkmeasuresthe replicationof

goods and services,it cannot easily incorporateeitherthe appearance of

entirelynew goods not presentat the startof a timeseriesor improvements

frustrate

overtimein the qualityof goods or services.New productsfurther

effortsat productivityestimationbecause the initialprices of new goods

wereusuallyveryhighbut declinedrapidlyas innovationproceeded,making

the calculationof both weightsand value-addeda majorproblem.49

calculations

Finally, the national accounts frameworkand productivity

in the means of production

cannot measure that qualitativeimprovement

whichcan yieldshorterworkinghoursor less arduousor monotonouswork

routines.50 Clearly, a broader concept of technologicalchange and of

innovationis required than can be accommodatedby national income

accounting.If the mostsensibleway to view the courseof economicchange

is throughthe timingand impactof innovation,it is arguablethatthe use

of nationalaccountinghas frustrated

progress.Emphasishas been placed on

at theexpenseofscience,economicorganization,

savingand capitalformation

the knacks

skills,dexterity,

new productsand processes,marketcreativity,

and otheraspectsof economiclifewhich

and workpracticesof manufacture,

may be innovativebut have no place in the accountingcategories.5'

The problemsinvolvedin measuringeconomy-wide

productivity

growth,

and in regardingit as a reflectionof the extentof fundamentaleconomic

change,are compoundedwhen one considersthe natureboth of industrial

capital and of industriallabour in the period. Redeploymentof labour

fromagrarian-basedand domesticsectorsto urban and more centralized

manufacturing

activitymay well have been accompaniedby diminishing

in the shortrun. Green labour had to learn industrial

labour productivity

skillsas well as new formsof disciplinewhile,withinsectors,labour often

shiftedinto processeswhich were more ratherthan less labour-intensive.

The same tendencyto low returnsin the shorttermcan be seen in capital

in theperiod.Earlysteamenginesand machinery

investment

wereimperfect

and subjectto breakdownsand rapidobsolescence.Grosscapitalinvestment

whenfed

figures(whichincludefundsspenton renewalsand replacements),

into productivity

of the importanceand

measures,are not a good reflection

potentialof technologicalchangein the period. Rapid technologicalchange

is capitalhungryas newequipmentsoonbecomesobsolescentand is replaced.

Shiftsin the aggregatemeasuresof productivity

growthare thus actually

less likelyto showup as significant

duringperiodsof rapidand fundamental

economictransition

thanin periodsofslowerand morepiecemealadjustment.

This pointwas stressedby Hicks who notedthatthelonggestationperiod

of technologicalinnovationmight yield Ricardo's machineryeffect:the

returnsfrommajor shiftsin technologywould not be apparentforseveral

wouldonlyincreaseunemployment

decadesand, in theshortterm,innovation

Brewer,McKendrick,and Plumb, Birthof a consumer

society;Breen, 'Baubles of Britain'.

Usher,Measurement,

pp. 8-io.

50

Ibid., p. 9.

51Ibid., p. io.

48

49

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

35

and put downwardpressure on wages.52There was such a disjuncture

betweenthe wave of innovationssurrounding

the electricdynamoin thelate

nineteenthcenturyand an accelerationin the growthof GNP. And the

currentcomputerrevolutionwhichis transforming

production,services,and

workinglives across a broad frontis not accompaniedby rapidlyrising

withinnationaleconomies.Resolvingthis

income,output,or productivity

apparent'productivity

paradox' involvesrecognizingthe limitednatureof

TFP as a measureof economicperformance

and the longtime-frame

needed

to connect fundamentaltechnologicalchange with productivity

growth.53

Thus, just as it is possible to have growthwithlittlechange,it is possible

to have radicalchangewithlimitedgrowth.In factthe more revolutionary

the changetechnologically,

socially,and culturally,the longerthismaytake

to workout in termsof conventionalmeasuresof economicperformance.

V

Anotherstrikingfeatureof the new orthodoxyis its restricteddefinition

oftheworkforce;

thisin turnhas implicationsfortheanalysisofproductivity

change as well as the standard of living debate. Wrigleyassessed key

productivitygrowthonly throughthe IO per cent of adult male labour

which,in i83I, workedin industriesservingdistantmarkets.Williamson's

documentationof inequalityand Lindert and Williamson'ssurveyof the

standard of living considered only adult male incomes while Lindert's

estimatesforindustrialoccupationsreliedon adult burialrecordswhichare

almost exclusivelymale. But the role of women and childrenin both

capital and labour intensivemarket-orientated

manufacturing

(in both the

'traditional'and the 'modern' sectors) probably reached a peak in the

industrialrevolution,makingit a unique periodin this respect.54

to quantifythe extentof femaleand child labour

It is extremelydifficult

as both were largelyexcluded fromofficialstatisticsand even fromwage

books. But analyses based only on adult male labour forcesare clearly

forthisperiod. On the supplyside the

inadequateand peculiarlydistorting

labourof womenand childrenwas a vitalpillarof householdincomes,made

more so by the populationgrowthand hence the age structureof the later

reducedthe proportionof males of

eighteenthcenturywhich substantially

52

question,

ch. 4. If patentingcan be taken

p. I53; Berg,Machinery

history,

Hicks, Theoryof economic

thenwe have some evidencethatgrowthof TFP in nineteenthas a roughindicationof inventiveness,

centuryEngland took place some 40 years afterthe accelerationof inventivepatentableactivity.See

revolution.

theindustrial

Sullivan,'England's "age of invention"',p. 444; Macleod, Inventing

53 David, 'The computerand the dynamo'.

54 Wrigley,Continuity,

chance and change,pp. 83-7; Williamson,Did Britishcapitalism?,passim;

pp. 4-5. In

growth,

Lindertand Williamson,'Englishworkers'livingstandards';Crafts,Britisheconomic

the woollenindustrywomen's and children'slabour accountedfor 75 per cent of the workforce,and

child labourexceededthatof womenand of men. Women and childrenalso predominatedin the cotton

industry;childrenunder I3 made up 20 per cent of the cottonfactoryworkforcein i8i6; thoseunder

female,and

i8, 5I.2 per cent. The silk, lace making,and knittingindustrieswere also predominantly

suchas theBirmingham

ofwomenand childrenin metalmanufactures

therewereevenhigherproportions

trades. See Randall, BeforetheLuddites,p. 6o; Nardinelli,'Child labour'; Berg, 'Women's work', pp.

70-3; Pinchbeck,Womenworkers,

passim; Saito, 'Otherfaces',p. i83; idem,'Labour supplybehaviour',

see Cunningham,

pp. 636 and 646. For a recentcriticaldiscussionof child labour and unemployment

passim.

'Employmentand unemployment',

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

36

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

workingage in the population.55The impactof the high dependencyratio

in

was cushionedby childrenearningtheirway at an earlyage, particularly

On the demand side the need for hand skills,

domesticmanufacturing.56

and workdisciplineencouragedthe absorptionof moreand more

dexterity,

femaleand juvenilelabour into commercialproduction.This was further

in wages which may have been increasing

encouragedby sex differentials

underthe impactof demographicpressurein theseyears.57Employerswere

much attractedby low wages and long hours at a time when no attention

ofpaymentby resultsor shorterhours.58

was yetpaid to theincentiveeffects

Thus factorsboth on the supply and on the demand side of the labour

marketresultedin a labour forcestructurewith high proportionsof child

and femaleworkers.They were the key elementsin the labour intensity,

and low productioncostsfoundin late eighteentheconomicdifferentiation,

centuryindustries.And this in turn influencedand was influencedby

innovation.New workdisciplines,new formsof subcontracting

and puttingout networks,new factoryorganization,and even new technologieswere

triedout initiallyon womenand children.59

The peculiar importanceof youthlabour in the industrialrevolutionis

in severalinstancesoftextileand othermachinery

beingdesigned

highlighted

The spinningjennywas a celebratedcase;

and builtto suitthe childworker.

the originalcountryjennyhad a horizontalwheel requiringa posturemost

forchildrenaged nineto twelve.Indeed, fora time,in the very

comfortable

earlyphases of mechanizationand factoryorganizationin the woollen and

silkindustriesas well as in cotton,it was generallybelievedthatchildlabour

was integralto textilemachine design.60This associationbetween child

labour and machinerywas confinedto a fairlybriefperiodof technological

United States it appears to have lasted from

change. In the north-eastern

c. i8I2 until the i83os, duringwhich time the proportionof women and

labour forcerose fromIO to 40 per

childrenin the entiremanufacturing

cent. This was associatedwithnew large-scaletechnologiesand divisionsof

labour specifically

designedto dispensewithmoreexpensiveand restrictive

skilled adult male labour.6' Similarly,the employmentof an increasing

proportionof femalelabour in English industrieswas also encouragedby

the readyreservesof cheap and skilledfemalelabour whichhad long been

a featureof domesticand workshopproduction.In addition,in England,

the process of

many agriculturalregionsshed femaleworkersfirst--during

55 Childrenaged 5-I4 probablyaccountedforbetween23 and 25 per cent of the totalpopulationin

the early nineteenthcentury,comparedwith 6 per cent in I95I. Wrigleyand Schofield,Population

history,

tab. A3.I, PP. 528-9.

56 Berg,Ageofmanufactures,

ch. 6; Medick,'Proto-industrial

familyeconomy';Levine,'Industrialisation

and the proletarianfamily',p. I77.

57 Saito, 'Other faces', p. i83; idem,'Labour supplybehaviour',p. 634.

58 Hobsbawm, 'Custom, wages and workload',pp. 353, 355.

59 Berg, 'Women's work', pp. 76-88; Pinchbeck,Womenworkers.

For modernThird World parallels

see Elson and Pearson, 'Nimble fingersand foreigninvestments',

pp. 2-3; Pearson, 'Female workers'.

60 Report. . . on thestateof children

on the

(P.P. i8i6, III), pp. 279, 343; ReportfromtheCommittee

bill to regulatethe labourof childrenin the millsand factories(P.P. i83I-2, XV), P. 254. The issue is

exploredin greaterdepth in Berg, 'Women's work'.

61 Goldin and Sokoloff,

p. 747; Goldin,'Economic statusof

'Women, childrenand industrialization',

women'.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

37

agriculturalchange,and much migrationwithinruralareas and fromrural

to urban areas consistedof youngwomenin searchof work.62

By mid centuryfemale and child labour was decliningin importance

througha mixtureof legislation,the activitiesof male tradeunionists,and

pervasiveideologyof the male breadwinnerand of fitand

the increasingly

proper female activities.63A patriarchalstance was by this time also

compatiblewith the economic aims of a broad spectrumof employers.

Accordingto Hobsbawm, largerscale employers(as well as male labour)

werelearningthe 'rules of the game' in whichhigherpayments(by results),

shorterworkinghours,and a negotiatedterrainof commoninterestscould

be substitutedforextensivelow-wageexploitationwithbeneficialeffectson

productivity.

The use of low-costchild and femalelabour was not, of course, new: it

had always been vital in the primarysectorand had been integralto the

spread of manufacturein the earlymodernperiod. What was new in the

periodof the classicindustrialrevolutionwas the extentof its incorporation

into rapidly expanding factoryand workshop manufacturingand its

of work, and labour

associationwith low wages, increasedintensification

undoubtedlyhad an impact

discipline.65The femaleand juvenileworkforce

on the outputfiguresper unit of input costs in manyindustries,but this

because some

would not necessarilybe reflectedin aggregateproductivity

femalelabour was a substituteformale: it increasedat timesand in sectors

high.66The social costs

wheremale wages werelow or male unemployment

in

transfer

through.poor

male

labour

payments

(felt high

of underutilized

of allowing for male unemploymentin

relief)as well as the difficulties

sectoralweightingsare likely to offsetgains in the measurableeconomic

oftheeconomy

indicatorsoftheperiod.The potentialeconomicperformance

limitedby the lack of incentiveto substitutecapital

as a whole was further

forlabourwhenthe labourof womenand childrenwas so abundant,cheap,

and disciplinedthroughfamilyworkgroupsand in theabsenceof traditions

of solidarity.67

The full effectsof this expandedrole of femaleand juvenilelabour can

62

Pollard,'Labour', p. I33; Bythell,Sweatedtrades;Berg, 'Women's work'; Allen,Enclosure,ch. I2;

Snell, Annals, chs. I and 4; Souden, 'East, west-home's best?', p. 307; cf. Williamson,Copingwith

citygrowth.

ch. 6; Seccombe, 'Emergenceof male breadwinner';Rose,

63 Lown, Womenand industrialization,

Harrison,'Class and gender',pp. I22-38, I45;

'Genderantagonism';Davidoffand Hall, Familyfortunes;

Roberts,Women'swork.

64

Hobsbawm, 'Custom, wages and workload',p. 36i.

65

families,

Levine, 'Industrialisationand the proletarianfamily',pp. I75-9; Levine, Reproducing

regionsis

economiesof the industrializing

pp. II2-5. The low wage characterof the export-orientated

pp. 937-45.

pp. I3I, I36-4I. See also Hunt, 'Industrialisation',

by Lee, TheBritisheconomy,

highlighted

Mokyr,echoingMarx, suggeststhatlow wagesmayhave been a keyfactorbehindthegrowthof modern

hours,

industry:'Has the industrialrevolutionbeen crowdedout?', p. 3i8. See also Bienefeld,Working

p. 4I. For parallelswiththe Third World see Pearson, 'Female workers'.

hypothesis'.

'Relativeproductivity

66 Saito,'Labour supplybehaviour',pp. 645-6;Goldinand Sokoloff,

of thissee Mincer,'Labour forceparticipation',and

For a standardtheoreticaland empiricaltreatment

Greenhalgh,'A labour supply function'.The male occupationalstatisticsupon which productivity

estimatesrely,necessarilytake no accountof unemployment.

ch. I2; Boyer, 'Old poor law'; Lyons,

67 Lewis, 'Economic development',p. 404; Allen, Enclosure,

'The Lancashirecottonindustry';Berg, 'Women's work'.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

38

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

only be completelyunderstoodat a disaggregatedlevel by analysingits

impact upon sectorsand in regionswhere it was cruciallyimportant.A

regionalperspectiveis also uniquely valuable in assessingthe extentand

natureof economicand social changein the period.

VI

The industrialrevolutionwas a periodof greatdisparityin regionalrates

regionswere

of change and economicfortunes.Expandingindustrializing

of

matchedby regionsof decliningindustry,and chronicunderutilization

agriculturewas similarly

labour and capital. The storyof commercializing

patchy.Slow-moving

aggregateindicatorsfailto capturethesedevelopments,

and self-reinforcing

drivecreatedby the developmentof

yetthe interactions

industryin markedregionalconcentrations

gave rise to major innovations.

For example,an increasein the outputof the Britishwool textilesectorby

centuryseems verymodest but

I50 per cent duringthe entireeighteenth

this conceals the dramaticrelocationtakingplace in favourof Yorkshire,

whose sharein nationalproductionrose fromaround20 per centto around

6o per cent in the course of the century.If the increasehad been uniform

in all regions,it could have been achievedsimplyby the gradualextension

commercialmethodsand productionfunctions.But Yorkshire's

oftraditional

embodieda revolution

in organizational

intensivegrowthnecessarily

patterns,

commerciallinks, credit relationships,the sorts of cloths produced, and

productiontechniques.The externaleconomiesachievedwhen one region

took over more than halfof the productionof an entiresectorwere also of

key importance.68

All the expanding industrialregions of the late eighteenthand early

nineteenthcenturieswere, like the West Riding, dominatedby particular

sectorsin a way neverexperiencedbeforenor to be experiencedagain after

the growthof intra-sectoral

century.

spatialhierarchiesduringthe twentieth

sectoralspecializationand regionalintegrity

togetherhelp to

Furthermore,

explain the emergenceof regionallydistinctivesocial and class relations

which set a patternin English political life for over a century.These

considerationspromptthe view thatregionalstudiesmay be of more value

in understanding

the processof industrialization

thanstudiesof the national

economyas a whole.69

The main justification

which Craftsuses for employingan aggregative

approachto identifythe nature,causes, and corollariesof industrialization

in Britainis that the nationaleconomyrepresented,formanyproducts,a

well integratednational goods marketby the early nineteenthcentury.

Althoughthe spread of fashionableconsumergoods was increasingand

nationalmarketsformuchbulk agricultural

producewereestablishedbefore

the mid eighteenthcentury,it cannotbe shownbeforethe second quarter

of the nineteenthcenturythatthe economyhad a 'fairlywell integratedset

68

The argumenthere and throughoutthis sectionis much influencedby Pollard,Peacefulconquest,

ch. I.

69 Fuller discussionof this can be found in Hudson, Regions,ch. i. For anotherexample of this

of Tyneside.

approachsee Levine and Wrightson,The making,on the earliertransformation

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

39

of factormarkets'.

70 The reallyimportant

spatialunitforproductionfactors,

especiallycapitaland labour,and forinformation

flow,commercialcontacts,

and credit networksin the pre-railwayperiod was the economic region,

which was oftenclearlyidentifiable.7'Constructionof the improvedriver

and canal systemson whicheconomicgrowthdependeddid muchto endorse

the existenceof regionaleconomies,fora timeincreasingtheirinsularity(in

relationto the nationaleconomy).72 Nor werethe railwaysquick to destroy

regionallyorientatedtransportsystems.Most companiesfound it in their

best intereststo structurefreightrates so as to encouragethe trade of the

regionsthey served, to favourshorthauls, and thus to cementregional

73

resourcegroupings.

Industrialization

accentuatedthe differences

betweenregionsby making

themmore functionally

distinctand specialized.Economicand commercial

circumstances

werethusincreasingly

experiencedregionally

and socialprotest

movementswiththeirregionalfragmentation

can onlybe understoodat that

level and in relationto regionalemployment

and social structures.Issues of

nationalpoliticalreformalso came to be identifiedwithparticularregions,

forexamplefactoryreformwithYorkshire,the anti-poorlaw campaignwith

Lancashireand Manchester,or currencyreformwithBirmingham.Regional

identitywas encouragedby the links createdaround the great provincial

cities,by theintra-regional

natureofthebulk ofmigration,

by theformation

ofregionallybased clubs and societies,tradeunions,employers'associations,

and newspapers.74

In short, dynamicindustrialregionsgenerateda social and economic

interaction

whichwould have been absentif theircomponentindustrieshad

not been spatiallyconcentratedand specialized.Intensivelocal competition

combined with regionalintelligenceand information

networkshelped to

stimulateregion-wideadvances in industrialtechnologyand commercial

organization.And thegrowthof specializedfinancialand mercantileservices

withinthe dominantregionsservedto increasethe externaleconomiesand

reduced both intra-regional

and extra-regional

transactionscosts significantly.75

Macroeconomicindicatorsfailto pick up thisregionalspecialization

and dynamismwhich was unique to the period and revolutionary

in its

impact.

Crafts,Britisheconomic

growth,p. 3.

Hunt, 'Industrialisation

and regionalinequality';idem,'Wages', pp. 6o-8; Allen,Enclosure,ch. I2;

Williamson,'English factormarkets';Clark and Souden, eds., Migrationand society,chs. 7, io. On

capital and credit marketssee Hudson, Genesis.See also Pollard, Peaceful conquest,p. 37; Presnell,

Countrybanking,pp. 284-343; Anderson,'Attorneyand the early capital market'; Hoppit, Risk and

failure,ch. I5.

72 Freeman, 'Transport', p. 86; Langton, 'Industrialrevolutionand regional geography',p. i62;

Turnbull,'Canals', pp. 537-60.

73 Freeman,'Transport',p. 92; see also Hawke, Railways.

74 Langtonprovidesa stimulating

surveyof the regionalfragmentation

of tradeunions,of Chartism

and othermovements,and of regionaldifferences

in work practicesand work customs,in 'Industrial

revolution',pp. I50-5. See also Read, Englishprovinces;and Southall, 'Towards a geography'which

concentrates

on the artisantrades.

75 See Pollard,Peacefulconquest,

pp. I9, 28-9.

70

7I

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

40

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

VII

The work of Wrigleyand Schofieldrightlydominatesthe population

historyof this period but theiroriginalcausal analysisillustratessome of

of aggregativestudiesof economicand social transformation.

the difficulties

They arguethat,despiteconsiderablegrowthin numbersand the disappeartherewas no significant

in

ance of major crises of mortality,

discontinuity

demographicbehaviourin England between the sixteenthand the mid

There was no sexual, social, medical,or nutritional

nineteenthcenturies.76

revolution.The population regime was and remained marriagedriven:

nuptialityand hence fertility

throughoutthe three centuriesvaried as a

delayed responseto changesin livingstandardsas indicatedby real wage

trends.77But the dangerin usingnationaldemographicvariablesto analyse

patternsof individualmotivationis that national estimatesmay conflate

opposing tendenciesin differentregions,sectors of industry,and social

of themainsprings

of aggregatedemographic

groups.Accurateidentification

trendswill onlycome withregional,sectoral,and class breakdownsbecause

sortsof workersor social groupswithindifferent

different

regionalcultures

stimulior reacted differently

to the same

probablyexperienceddifferent

economictrends,thus creatinga rangeof demographicregimes.78

The factthatdemographicvariablessuch as illegitimacy

ratesand age of

marriageexhibitenduringspatialpatternsin the face of changingeconomic

fortunesis suggestive.79Parish reconstitution

studies indicate that local

behaviour did not parallel the movementof the aggregateseries. Such

diversitycasts doubt upon the use of the nationalvital rates for causal

analysisof demographicbehaviour.The mostimportantcausal variablesin

local reconstitution

studiesappear to range well outside the movementof

real wages. The local economic and social setting,broadlydefined,was

crucial. It included such thingsas proletarianization,

price movements,

and the natureof parishadministration,

of

economicinsecurity,

particularly

the poor laws.80 Despite this, a national culturalnorm continuesto be

stressed,withthe assumptionthatregionsand localitiestendedtowardsit.

The result,as with the macroeconomicwork of Craftsand others,is an

excessivepreoccupationwithnationalcomparisons('the French versusthe

Englishpattern')and withthe idea thatlowerclasses and backwardregions

lag behindtheirsuperiors,but eventuallyfollowthemon the nationalroad

to modernityand progress.8'

76 Wrigleyand Schofield,Populationhistory,

chs. I0, i i. For summariesof theircausal analysissee

Smith,'Fertility,economyand householdformation';Wrigley,'Growthof population'.

77 There has been considerable

theanalysis.

methodunderlying

debateoverthisviewand thestatistical

See Gaunt,Levine, and Moodie, 'Populationhistory';Anderson,'Historicaldemography';Mokyr,'Three

centuriesof populationchange'; Olney, 'Fertility';Lindert, 'English livingstandards';Lee, 'Inverse

projection';idem,'Populationhomeostatis'.

78 See Levine, in Gaunt, Levine, and Moodie, 'Populationhistory',p. I55.

79 See for example, Levine and Wrightson,'Social context of illegitimacy',pp. i6o-i;

Wilson,

'Proximatedeterminants'.

80 Wrightsonand Levine, Povertyand piety.For the importanceof the local economic settingsee

Levine and Wrightson,The making,ch. 3; Sharpe, 'Literallyspinsters'.For

Levine, Familyformation;

familyreconstitution

resultssee Wrigleyand Schofield,'Englishpopulationhistory'.

81 Seccombe, 'Marxismand demography',

p. 35.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

4I

and the

Recently,the effectsof proto-industrialization,

proletarianization,

changingcompositionof the workforcehave receivedattentionin relation

todemographic

change.82This opensthedoorfora moreradicalinterpretation

of the structuralcauses of fertility

change. The need to look more closely

at those structuraland institutional

changeswhichresultedin the marked

declinein age of marriagein the second halfof the eighteenthcenturyhas

been emphasized, as has the importanceof a growinggroup of 'young

barriers' in the populationwhose actionsappear unaffected

by the general

pressureson real wages.83Evidence of radical discontinuity

is reappearing

at all levels of analysis.84

The influenceoftheWrigley/Schofield

approachmayalso haveunjustifiably

divertedattentionaway frommortalityand its significant

discontinuities.

The CambridgeGroup aggregatedata suggestthatrisingfertility

was twoand-a-halftimes more importantthan fallingmortalityin producingthe

accelerationin population growthin the eighteenthcentury. But the

markedincreasein theproportionof thepopulationlivingin townstogether

withthe substantialurbanmortality

penaltymakesdiachronicstudiesof the

national aggregate population particularlylikely to underestimatethe

A centralrole for

importanceof mortalitychangesin relationto fertility.

in urbanlifeexpectancyin fuellingpopulationgrowthduring

improvements

theindustrialrevolution

is perfectly

compatiblewithsignificant

contemporary

shiftsin fertility

and even withsuch shiftsbeing apparently

moresignificant

at the nationallevel.86

ofradicalstructural

The significance

shiftsin thecompositionand location

in mortality

of the population,as well as of improvement

rates,tendsto be

overlookedif causal explanationsbased on aggregatedata are used. This has

resultedin the currentliteraturebeing dominatedby discussionof fertility

ratherthan of mortality

and of continuity

ratherthanof discontinuity.

VIII

The evolutionof social class and of class consciousnesshas long been

integral to popular understandingof what was new in the industrial

revolution.Growingoccupationalconcentration,

loss of

proletarianization,

independence,exploitation,deskilling,and urbanizationhave been central

ofworking-class

cultureand consciousness,

to mostanalysesoftheformation

while the ascendancy of Whig laissez-fairepolitical economy has been

as a class.87But recent

associatedwiththe new importanceof industrialists

families,chs. 2, 3; idem,'Proletarianfamily',pp. i8i-8.

See Levine, Reproducing

Schofield,'English marriagepatterns'.This studyfindsthat, in the eighteenthcentury,age of

and

marriagebecame more importantthan variationin celibacyin accountingforchangesin fertility,

thatage of marriagewas relativelyunresponsiveto real wage indicesafterI700. On youngmarrierssee

Goldstone,'Demographicrevolution'.

84

For a recentexamplesee Jackson,'Populationchangein Somerset-Wiltshire'.

85

Wrigley,'Growthof populationin the eighteenthcentury',pp. I26-33.

86

This pointis made in Kearns, 'Urban penalty';cf. Thompson,

Woods, 'Populationredistribution'.

The making,pp. 356-66; Perkin,Origins.

87

Prothero,Artisansand politics;Morris, Class and class

See, for example, Foster, Class struggle;

Seed, 'Unitarianism'.

consciousness;

82

83

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

42

MAXINE

BERG

and

PAT HUDSON

economichistoryhas rightlyemphasizedthe complexityof combinedand

unevendevelopment.Putting-out,

workshops,and sweatingexistedalongside

and werecomplementary

to a diversefactorysector.It is no longerpossible

to speak of a unilinearprocessof deskillingand loss of workplacecontrol.

The diversityof organizationalforms of industry,of work experience

of compositeand irregularincomes,and

accordingto genderand ethnicity,

of shiftsof employmentover the lifecycle and throughthe seasons meant

that workers'perceptionsof work and of an employingclass were varied

and contradictory.88

Nor can one speakofa homogeneousgroupofindustrial

betweenthe attitudeand outlook

employers.There weremarkeddifferences

of small workshopmastersand factoryemployers.And withinthesegroups

therewere variationsof responseto competitiveconditionsrangingfrom

outrightexploitationto paternalism,withmanymixturesof the two. There

fromagentsdown to foremenand

was also a wide rangeof intermediaries

leaders of familywork groups to deflectoppositionand tension in the

workplace.89And we now have a much more sophisticatedunderstanding

of the complexinterplayof customaryand marketrelationships.

Any simple

notionof the latterreplacingthe formeris to be discarded.90In addition,

recentwriting,includingpost-structuralist

approaches,has questionedany

suggestionof deterministic

relationshipsbetween socioeconomic position

and politicalconsciousness.9'

of thiswork,theseinterpretations

should not be

Despite the significance

allowed to edge out all idea thatthe industrialrevolutionperiod witnessed

radical shiftsin social relationsand in social consciousness.Much recent

social historyhas been based on an unquestioningacceptanceof the new

gradualistviewoftheeconomichistoryoftheperiodwhich,we have argued,

severelyunderplaysthe extentof radical economicchange and of parallel

the mass of the population.Balanced analysesof the

developmentsaffecting

combinedand uneven natureof developmentwithinindustrialcapitalism

should not obscure the fact that the industrialworld of I850 was vastly

differentfor most workersfrom that of I750. There were more large

workplaces,more poweredmachines,and along withthesetherewas more

directmanagerialinvolvementin the organizationand planningof work. A

clearernotionof the separationof work and non-worktime was evolving

partlyout of thedeclineoffamilyworkunitsand ofproductionin thehome.

had acceleratedand the life chances of a much larger

Proletarianization

proportionof the populationwere determinedby the marketand affected

and disease. Capitalistwage labourand theworkingclass

by urbanmortality

88 Joyce,'Work'; idem,'Introduction'in idem,Historicalmeanings;

Samuel, 'Workshop'; Sabel and

Zeitlin,'Historicalalternatives';Reid, 'Politicsand economics';Hobsbawm, 'Marx and history'.

89

Davidoff and Hall, Family fortunes;Behagg, Productionand politics;Rodger, 'Mid Victorian

employers';Joyce,'Work'; Huberman,'Economicoriginsof paternalism';Rose, Taylor,and Winstanley,

'Economic origins. . . objections';Huberman,'Reply'.

90 Williams,'Custom'; Bushaway,By rite;Randall, 'Industrialmoral economy'; Berg, ed., Markets

and manufacture.

Sonenscher,Workin France;

91 StedmanJones,'RethinkingChartism';Sewell, Workand revolution;

Foster, 'Declassing of language'; Gray,'Deconstructionof the Englishworkingclass'; idem,'Language

chs. I-3; Patterson,'Postof factoryreform';Reddy, Money and liberty;Scott, Genderand history,

structuralism'.

This content downloaded from 128.205.114.91 on Wed, 28 May 2014 10:42:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REHABILITATING

THE

INDUSTRIAL

REVOLUTION

43

but withgreaterspeed thanin earlier

and incompletely

developedirregularly

of similarities

of workexperience

centuries.And the regionalconcentration

to producesocial

sufficiently

and of the tradecycleadvancedclass formation

protestand conflicton an unprecedentedscale, involvingan arrayof anticapitalistcritiques.92

nationally,

While the factoryneverdominatedproductionor employment

in certainregionsto create widespreadidentitiesof

it did so sufficiently

interestand political cohesion. And where it did not exist it exercised

enormous influencenot only in spawning dispersed production, suband sweating,but also as a majorfeatureof the imageryof the

contracting,

age. The factoryand the machineas hallmarksof the periodmayhave been

mythbut they were symbolicof many other changes attendanton the

emergenceof a more competitivemarket environmentand the greater

discipliningand alienationoflabour.This symbolprovideda focusofprotest

and opposition and was a powerfulelement in the formationof social

consciousness.93

Finally,we mustconsiderthe prominencerecentlygivento the economic

power and political influenceof the landed aristocracy,rentiers,and

merchantsin the nineteenthcentury.94This prominenceis, in part, a

of industrialchange and

response to the new gradualistinterpretations

The

division