Job Design Theory and Application to the

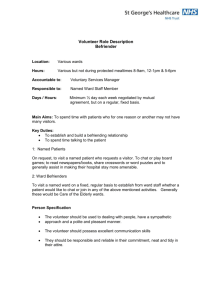

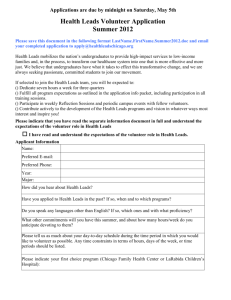

advertisement