INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE AND THE

advertisement

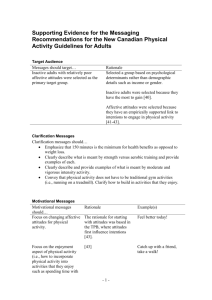

Social Cognition, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2006, pp. 453-468 HUSKINSON DIFFERENCES INDIVIDUAL AND HADDOCKIN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE AND THE ACCESSIBILITY OF THE AFFECTIVE AND COGNITIVE COMPONENTS OF ATTITUDE Thomas L. H. Huskinson and Geoffrey Haddock Cardiff University Research has demonstrated that some individuals possess attitudes that are highly consistent with both their feelings and beliefs, whereas other individuals possess attitudes that are less consistent with these sources of information (Haddock & Huskinson, 2004). The current research investigated whether individuals with strongly versus weakly structured attitudes differ in the accessibility of their affective and cognitive responses. In two experiments, participants provided timed affective and cognitive judgments toward different attitude objects. Overall, individuals with highly structured attitudes provided faster affective and cognitive attitudinal responses. Affective responses were also made more quickly than cognitive responses. Two additional experiments ruled out the possibility of a generalized response latency advantage for individuals with highly structured attitudes. The results speak to the importance of considering individual differences in how people organize their attitudes, as well as the distinction between the affective and cognitive components of attitude. The multicomponent model of attitudes (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Zanna & Rempel, 1988) states that attitudes are overall evaluations of stimuli that are derived from the favorability of an individual’s affects, cognitions, and past behaviors. Affective We thank Don Carlston, Greg Maio, and Russell Spears for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article. Address correspondence to Geoff Haddock, School of Psychology, P. O. Box 901, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK; E–mail: HaddockGG@Cardiff.ac.uk 453 454 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK information refers to feelings an individual associates with an attitude object. Cognitive information refers to beliefs or attributes an individual associates with an attitude object. Behavioral information refers to past behaviors or behavioral intentions relevant to an attitude object. The multicomponent model raises a variety of interesting questions. For example, do people differ in the degree to which their attitudes are consistent with both their feelings and beliefs? That is, do some people have attitudes that are highly consistent with the favorability of both their affects and cognitions, whereas other people have attitudes that are less consistent with these sources of information? If so, what are the consequences of such differences? Second, which of the attitudinal components is more accessible? For example, are affective responses more accessible than cognitive responses? These questions motivated the present research, which investigated whether generally having strongly versus weakly structured attitudes is associated with differences in the accessibility of affective and cognitive responses. AFFECT, COGNITION, AND INDIVIDUAL ATTITUDES Research suggests that the contribution of affect and cognition to the prediction of individual attitudes depends upon the attitude object in question.1 For instance, Abelson, Kinder, Peters, and Fiske (1982) found affective information to be a better predictor of attitudes toward politicians than cognitive information. Conversely, Eagly, Mladinic, and Otto (1994; Study 2) found cognitive information to be more important than affect in predicting attitudes toward various social policy issues. Other studies have also demonstrated that the unique contribution of affective and cognitive information varies across attitude objects (e.g., Breckler & Wiggins, 1989; Esses, Haddock, & Zanna, 1993). It appears then 1. In line with recent research (e.g., Chaiken, Pomerantz, & Giner-Sorolla, 1995; Huskinson & Haddock, 2004; Verplanken, Hofstee, & Janssen, 1998) we shall be concentrating solely on the affective and cognitive components of attitude. For a discussion of the role of behavioral information in predicting individual attitudes see Haddock, Zanna, and Esses (1994). INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 455 that objects differ in whether individuals’ attitudes toward them are based primarily upon affect or cognition. The accessibility of the affective and cognitive components of attitude may also vary. Verplanken, Hofstee, and Janssen (1998; Study 4) recorded the time it took participants to make affective and cognitive judgments toward various countries. For each country, participants were presented with a series of adjective pairs on a computer screen, some of which were affective (e.g., unpleasant/pleasant), others of which were cognitive (e.g., modern/traditional). Participants indicated which of the two adjectives in each pair best described their feelings/thoughts toward the object. Verplanken et al. (1998) found that affective judgments were made more quickly than cognitive judgments. In related research, Giner–Sorolla (2001) explored the accessibility of affect– and cognition–based attitudes. In this research, attitude objects were selected on the basis of being affect– or cognition–based. Giner–Sorolla (2001) found that affect–based attitudes were more accessible than cognition–based attitudes only when attitudes were extreme. This finding diverges from that of Verplanken et al. (1998). These conflicting results may be due to the different judgments investigated in the studies: affective and cognitive information per se in Verplanken et al.’s (1998) research, but affect– and cognition–based attitudes in Giner–Sorolla’s (2001) research. While affective information may be more accessible than cognitive information (as demonstrated by Verplanken et al., 1998), attitudes may become detached from the information upon which they were originally based (see Zanna & Rempel, 1988), annulling any accessibility advantage of affect–based attitudes. Finally, other work has investigated the consistency among attitudes, affects, and cognitions about single objects. This research suggests that attitudes lacking affective and cognitive consistency are weaker than attitudes with strong support. For instance, Chaiken and Baldwin (1981) found that individuals with low evaluative–cognitive (E–C) consistency (i.e., low consistency between the favorability of their measured attitude and beliefs) were more susceptible to self–perception effects than individuals with high E–C consistency. Chaiken, Pomerantz, and Giner–Sorolla (1995) extended this research by considering both 456 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK evaluative–affective (E–A) and evaluative–cognitive consistency. Using the attitude object of capital punishment, these researchers found that individuals high in both E–A and E–C consistency (e.g., people with a positive attitude, feelings, and beliefs about capital punishment) had more accessible and more stable attitudes than individuals low in both types of consistency (e.g., people with a positive attitude but neutral feelings and beliefs about capital punishment). Interestingly, Chaiken et al. reported no differences in accessibility among individuals high in one type of consistency but low in the other; the observed difference was restricted to less accessible attitudes among individuals low in both E–A and E–C consistency. INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE A small body of research has explored the possibility that structural differences in attitudes may also exist across individuals. That is, people may vary in the extent to which they derive their attitudes from affective and cognitive information. While a minority of people can be expected to rely more on either affective or cognitive information, the synergistic relation between affect and cognition (see Breckler, 1984; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993) suggests that most people are likely to rely upon both affect and cognition to a relatively equal strong or equally weak degree. Some people might generally possess attitudes that are highly consistent with the favorability of both their feelings and beliefs, while other people might generally possess attitudes that are less consistent with the favorability of their feelings and beliefs. It is these individuals with strongly or weakly structured attitudes who are the focus of the present article. The existence of individual differences in attitude structure has been demonstrated. Haddock and Huskinson (2004; see also Huskinson & Haddock, 2004) asked participants to complete measures of attitude, affect, and cognition for numerous attitude objects. Using within–person correlations, they found that individuals differed considerably in evaluative–affective and evaluative–cognitive consistency. Given the synergistic relation between affect and cognition, they found that most respondents (approximately 70%) possessed attitudes that were either equally INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 457 high or equally low in both E–A and E–C consistency. Further, such variability was associated with individual differences in the Need to Evaluate (Jarvis & Petty, 1996), such that individuals low in both evaluative–affective and evaluative–cognitive consistency were also low in the Need to Evaluate. Importantly, these structural differences have been found to be consequential. In a task where participants had to list affects and cognitions associated with the behavior of exercising, individuals high in both E–A and E–C consistency clustered their responses by valence, whereas individuals low in both E–A and E–C consistency did not (Huskinson & Haddock, 2006; see Trafimow & Sheeran, 1998). THE PRESENT RESEARCH The present research investigated whether individuals possessing strongly versus weakly structured attitudes differ in the accessibility of their affective and cognitive responses. We focused our research on individuals with strongly versus weakly structured attitudes because past research has demonstrated that these individuals differ in the degree to which they respond to questions assessing attitude strength, whereas individuals with structural dissociations (i.e., high evaluative–affective consistency/low evaluative–cognitive consistency, and vice versa) do not (Huskinson & Haddock, 2006). As noted earlier, Chaiken et al. (1995) found that low evaluative–affective and evaluative–cognitive consistency were associated with less accessible attitudes toward a single object. Congruent with Chaiken et al.’s (1995) findings, we reasoned that individuals whose attitudes are high in both E–A and E–C consistency (individuals we refer to as Dual–Consistents [DCs]) would provide faster affective and cognitive judgments than those individuals whose attitudes are low in both E–A and E–C consistency (individuals we refer to as Dual–Inconsistents [DIs]). Additional rationale for this notion comes from Fazio (1995), who argued that an attitude is accessible to the extent that the information upon which it is based is perceived as diagnostic by the individual. Diagnosticity comes about through individuals learning to trust some classes of information as more indicative of their attitudes than other classes of information. In the present context, 458 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK dual–consistents may perceive their affects and cognitions as more diagnostic of their attitudes, which should elicit faster (i.e., more accessible) affective and cognitive responses. To address this issue, individuals with highly or weakly structured attitudes were presented with items on a computer screen corresponding to affective (e.g., unpleasant/pleasant) and cognitive (e.g., modern/traditional) dimensions. The task of participants was to indicate which of the two words from each pair best described their thoughts/feelings toward the object in question. On the basis of previous findings (e.g., Chaiken et al., 1995; Verplanken et al., 1998), we hypothesized: (1) that individuals with highly structured attitudes would respond faster than individuals with weakly structured attitudes, and (2) that affective judgments would be made faster than cognitive judgments. These predictions were tested in two separate experiments using different attitude objects and different affective and cognitive adjective pairs. EXPERIMENTS 1A AND 1B OVERVIEW AND DETERMINATION OF ATTITUDE STRUCTURE CLASSIFICATION Data were collected in three different waves of participants over three different academic years. At the beginning of the academic year, participants in each wave took part in a study in which they completed semantic differential measures of attitude, affect, and cognition (see Crites, Fabrigar, & Petty, 1994) toward diverse attitude objects (e.g., abortion, Germans, spiders). Their responses were then used to compute within–person correlations for each participant. A measure of evaluative–affective consistency was computed by correlating a participant’s attitude and affect responses across all attitude objects, and a measure of evaluative–cognitive consistency was computed by correlating their attitude and cognition responses across all attitude objects. As these indices are derived from multiple attitude objects for each individual, they represent the extent to which an individual generally maintains attitudes consistent with affective and cognitive information. An individual was categorized as having highly INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 459 structured attitudes if both his or her E–A and E–C correlations fell above the medians, whereas an individual was categorized as having weakly structured attitudes if both his or her E–A and E–C correlations fell below the medians.2 Approximately four months after completing this initial assessment, a random selection of individuals with highly or weakly structured attitudes returned to the lab for two different accessibility studies. Experiment 1A used a procedure that was conceptually identical to research by Verplanken et al. (1998; Study 4). Participants evaluated a number of countries on a series of affective and cognitive dimensions. Their task was to indicate which word from the pair best represented their impression of each country. In Experiment 1B, participants evaluated a different set of attitude objects using a different set of affective and cognitive dimensions. In both experiments, participants’ responses were timed to provide affective and cognitive component accessibility data for each participant. METHOD Participants. Ninety–three participants, (ten male, 81 female, two did not provide this information; mean age = 19 years) who, on the basis of their attitude structure classification, fit the criteria for a dual–consistent or dual–inconsistent, participated in return for course credit. Design. Each study used a mixed–model design. The between–person variables were attitude structure classification (dual–consistent vs. dual–inconsistent) and data wave session (wave 1–3). The within–person independent variables were attitude component item type (affective vs. cognitive) and attitude object (ten countries in Experiment 1A; four different objects in Experiment 1B; see below for individual items). Materials and Procedure. Participants took part individually. The experimenter indicated that the session would involve a series of 2. Across the three waves, approximately 70% of respondents in the initial assessment met our classification for having strongly or weakly structures attitudes (approximately 35% in each category). The remaining participants possessed attitudes that were predominantly consistent with either their feelings or beliefs. 460 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK short experiments. Participants were then seated at a computer with instructions on the monitor. The instructions were also read aloud to them by the experimenter. In Experiment 1A, the instructions explained that they would be asked to make a series of decisions about different countries. They were told that for each country, a series of bipolar adjectives would be presented consecutively on the screen. They were instructed that for each adjective pair, they needed to indicate which of the items best represented their impression of the country (this was done by pressing one of two buttons on the keyboard). They were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. Finally, they were instructed that the first country presented was a practice trial. There were ten different countries used in Experiment 1A (excluding the practice trial): France, Germany, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. The affective bipolar adjectives used in conjunction with these stimuli were: aggressive/peaceful, beautiful/ugly, gloomy/cheerful, enjoyable/unenjoyable, exciting/dull, nervous/calm, romantic/not romantic, and unfriendly/friendly. The cognitive bipolar adjectives used in conjunction with these stimuli were: dry/wet, full/empty, flat/hilly, large/small, modern/traditional, north/south, sparsely populated/densely populated, and woody/bare (see Verplanken et al., 1998). 3 After a filler task, participants completed Experiment 1B. There were four attitude objects used in this study: blood donation, capital punishment, the British Monarchy, and Tony Blair. The affective bipolar adjectives used in conjunction with these stimuli were: acceptance/disgusted, angry/relaxed, excited/bored, joy/sorrow, happy/annoyed, love/hateful, sadness/delighted, and tense/calm. The cognitive bipolar adjectives used in conjunction with these stimuli were: foolish/wise, harmful/beneficial, imperfect/perfect, safe/unsafe, useful/useless, valuable/worthless, and wholesome/unhealthy (see Crites et al., 1994). 3. In both studies, the order of attitude object presentation was randomized for each participant, as was the order of affective and cognitive bipolar adjectives for each attitude object. INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 461 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION In both experiments, responses to items were log–transformed, and separate affect and cognition scores were computed for each participant by computing the mean latency across the relevant items. Responses less than 300 ms or greater than 3,000 ms, which accounted for 6.8% of the data in Experiment 1A and 5.2% of the data in Experiment 1B, were removed. In Experiment 1A, the results of the analysis revealed two relevant significant effects. First, individuals with highly structured attitudes (M = 1,257 ms) made faster responses than individuals with weakly structured attitudes (M = 1,315 ms; see Figure 1), F(1, 85) = 3.05, p = .08. Second, affective responses (M = 1,191 ms) were made faster than cognitive responses (M = 1,388 ms), F(1, 85) = 157.84, p < .001.4 The results of Experiment 1B revealed a similar pattern. First, individuals with highly structured attitudes (M = 1,167 ms) made faster responses than individuals with weakly structured attitudes (M = 1,285 ms; see Figure 2), F(1, 81) = 3.99, p < .05. Second, affective responses (M = 1210 ms) were made faster than cognitive responses (M = 1,248 ms), F(1, 81) = 2.74, p = .10.5 Given the consistent findings across the experiments, we conducted a meta–analysis to determine the studies’ combined effects. Using a combined probability framework (see Rosenthal, 1991), this analysis revealed two significant effects. First, individuals with strongly structured attitudes provided faster judgments than individuals with weakly structured attitudes (p = 4. Three other, less theoretically relevant effects also emerged. There was a main effect of data wave [F(2, 85) = 2.99, p = .05], suggesting that the waves differed in overall accessibility. There was also a main effect of country [F(9, 77) = 5.64, p 001], suggesting that accessibility differed across countries. Finally, there was an interaction between country and component [F(9, 77) = 9.90, p .001], suggesting that the difference between reaction times for affect and cognition differed across countries. 5. Variation in degrees of freedom from Experiment 1A reflects differences in patterns of missing data. Similar to Experiment 1A, the same three less theoretically relevant effects also emerged. There was a marginal main effect of data wave [F (2, 81) = 2.41, p = .10], suggesting that the waves differed in overall accessibility. There was also a main effect of object [F (3, 79) = 9.67, p 001], suggesting that accessibility differed across objects. Finally, there was a marginally significant interaction between object and component [F (3, 79) = 2.42, p = .07], suggesting that the difference between reaction times for affect and cognition differed across objects. Mean Response Time (ms) 462 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK 1400 1300 Affect Words Cognition Words 1200 1100 Dual-Consistents Dual-Inconsistents FIGURE 1. Experiment 1A: Response latencies as a function of individual differences and attitude component. .009). Second, affective judgments were made faster than cognitive judgments (p = .005). These results provide support for the contention that the accessibility of affective and cognitive judgments differs across individuals, depending on the consistency among their attitudes, feelings, and beliefs. Individuals who generally maintained attitudes highly consistent with both their affects and cognitions provided faster affective and cognitive judgments than individuals whose attitudes were less consistent with their feelings and beliefs. These results also revealed an accessibility advantage for affective information, replicating previous research. While Experiments 1A and 1B provided convergent evidence, one could argue that individuals with highly structured attitudes might be faster in all types of judgments, including judgments not relevant to attitudes. Rather than arguing for a general response latency advantage for dual–consistents, we would like to suggest that their advantage is limited to attitude–based judgments. If individuals with highly structured attitudes are faster to respond to affective and cognitive attitudinal items because they view these items as diagnostic of their attitudes, there is no reason to expect speed differences for non-evaluative judgments. We therefore conducted two additional studies that tested whether individuals with INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 463 Mean Response Time (ms) 1300 1250 Affect Words Cognition Words 1200 1150 1100 Dual-Consistents Dual-Inconsistents FIGURE 2. Experiment 1B: Response latencies as a function of individual differences and attitude component. highly or weakly structured attitudes differed in how quickly they responded to non-evaluative judgments. If the response latency difference between dual–consistents and dual–inconsistents is limited to attitudinally relevant judgments, these studies should reveal no latency differences between the groups. EXPERIMENTS 2A AND 2B METHOD Participants. Participants were 38 individuals (four males, 34 females; mean age = 19.0 years) who, on the basis of their attitude structure classification study, fit the criteria for being a dual–consistent or dual–inconsistent.6 Procedure. In Experiment 2A, participants completed a lexical decision task. They were seated at a computer and instructed that a series of letter strings would appear in the center of the screen. They were instructed to judge whether the letter string was a word or non–word, and to press a key indicating their response. 6. In all of the research reported in this article, the predominance of female participants is a reflection of the undergraduate psychology population from which we sampled. 464 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK They were told to complete this task as quickly and accurately as possible. There were 12 words (e.g., print) and 12 non–words (e.g., prult). After a filler task, participants completed Experiment 2B. In this task, they responded to a series of general knowledge questions (e.g., “What is the capital of Canada?”; “Which band had a hit with ‘Jumping Jack Flash?’ ”). For each question, they were given two alternatives; their task was to press the key corresponding to the correct answer as quickly as possible. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION As in the other experiments, responses were log–transformed. In each experiment, responses across items (e.g., speed of responses to proper words in Experiment 2A; speed of responses to knowledge questions in Experiment 2B) were combined to form single latency scores for each individual for each task. Separate ANOVAs were performed on responses to the lexical decision and general knowledge tasks. In both experiments, there was no difference in response times between individuals with highly versus weakly structured attitudes, both Fs < 1. Furthermore, there were no differences between groups in the number of correct responses on the general knowledge task, F(1, 32) = 1.12, ns.7 Taken together, the results of Experiments 2A and 2B demonstrated that individuals with highly versus weakly structured attitudes did not differ in the speed with which they made non–evaluative judgments. These results support the contention that the component accessibility advantage shown in Experiments 1A and 1B was not attributable to a general speed advantage. Rather, they are consistent with the proposal that response latency differences are limited to attitude–based judgments. 7. Much to our surprise (and disappointment), approximately 35% of our participants responded that Montréal is the capital of Canada and that The Who had a hit with “Jumping Jack Flash.” INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 465 GENERAL DISCUSSION Across two experiments (1A and 1B), individuals whose attitudes were highly consistent with both their feelings and beliefs provided faster affective and cognitive attitudinal judgments compared to individuals whose attitudes were less affect– and cognition–consistent. Two additional experiments (2A and 2B) ruled out a general response latency advantage for individuals with highly structured attitudes. The attitude component accessibility advantage is compelling when one considers the temporal separation (approximately four months) between the session in which the attitude structure classification was derived and the session in which the accessibility data were gathered. The use of such a temporal lag offers impressive testimony regarding the stability of the obtained effects. These results have a number of important implications regarding the role of individual differences in attitude structure. For instance, they are instructive when considered in light of past research on attitude accessibility and attitude structure. Chaiken et al. (1995) reported that attitudes toward capital punishment were more accessible when they had evaluatively consistent support from feelings and beliefs, concluding that attitudes are strong to the extent that they are high in evaluative–affective and evaluative–cognitive consistency. The present research extrapolated this finding to the individual level, as well as to the component level, suggesting that individuals with highly structured attitudes, given the evaluatively consistent support for their attitudes from both their affects and cognitions, possess a general latency advantage for affective and cognitive responses. The current findings are also consistent with Fazio (1995), who argued that an attitude will be accessible to the extent that the information upon which it is based is perceived as diagnostic by the individual. Although no direct measure of diagnosticity was included in the present research, the mechanism is consistent with the present results. To the extent that both their feelings and beliefs are highly consistent with their attitudes, individuals with highly structured attitudes may hold their affects and cognitions with greater confidence, resulting in their affects and cognitions being more accessible. 466 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK One interesting line of inquiry arising from the present research concerns upon what exactly individuals low in both evaluative–affective and evaluative–cognitive consistency base their attitudes. One possibility is that the behavioral component might be a particularly important antecedent for these individuals. In line with this notion, at the level of a single attitude object, Chaiken and Baldwin (1981) demonstrated that individuals low in E–C consistency were particularly susceptible to self–perception effects. Future research might investigate whether individuals low in both E–A and E–C consistency are most inclined to show evidence of self–perception. A second goal of the research was to contribute to the literature regarding the accessibility of affective and cognitive information. Verplanken et al. (1998) demonstrated that affective information was more accessible than cognitive information. In the present research, two separate studies, using different types of attitude objects and affective–cognitive dimensions, provided support for differences in accessibility for affective and cognitive information. These findings are relevant to discussions regarding the relative accessibility of affect and cognition. It has been argued that affect can be elicited in the absence of prior cognitive processes, and should be considered as more primary than cognition (e.g., Murphy & Zajonc, 1993; Zajonc, 1980; cf. Lazarus, 1984). The present results are consistent with such theorizing—affective judgments were made faster than cognitive judgments toward a range of attitude objects—although other explanations could also possibly account for such a finding. Perhaps the general need to ascertain the truth or falsity of cognitive as opposed to affective judgments contributes to the accessibility advantage of affective information. It is instructive in this regard to note that Experiment 1A, which employed cognitive items of a more factual nature, obtained more of an affect accessibility advantage than Experiment 1B, which employed cognitive items that were more evaluative in nature. A further possibility, raised by Verplanken et al. (1998), is that affective judgments may be less complex in nature than cognitive information. Whereas affective judgments can simply refer to a general feeling state toward an object, cognitive judgments may involve the deliberation of a variety of contingencies and factors to arrive at a judgment. Understanding the mechanism(s) INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ATTITUDE STRUCTURE 467 behind this affect accessibility advantage is an issue that is worthy of additional research. REFERENCES Abelson, R. P., Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., & Fiske, S. T. (1982). Affective and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 619–630. Breckler, S. J. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1191–1205. Breckler, S. J., & Wiggins, E. C. (1989). Affect versus evaluation in the structure of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 253–271. Chaiken, S., & Baldwin, M. W. (1981). Affective–cognitive consistency and the effect of salient behavioral information on the self–perception of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 1–12. Chaiken, S., Pomerantz, E. M., & Giner–Sorolla, R. (1995). Structural consistency and attitude strength. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 387–412). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Crites, S. L., Fabrigar, L. R., & Petty, R. E. (1994). Measuring the affective and cognitive properties of attitudes: Conceptual and methodological issues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 619–634. Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Eagly, A. H., Mladinic, A., & Otto, S. (1994). Cognitive and affective bases of attitudes toward social groups and social policies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 113–137. Esses, V. M., Haddock, G., & Zanna, M. P. (1993). Values, stereotypes, and emotions as determinants of intergroup attitudes. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, cognition and stereotyping: Interactive processes in group perception (pp. 137–166). New York: Academic Press. Fazio, R, H. (1995). Attitudes as object–evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Giner–Sorolla, R. (2001). Affective attitudes are not always faster: The moderating role of extremity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 666–675. Haddock, G., & Huskinson, T. L. H. (2004). Individual differences in attitude structure. In G. Haddock & G. R. O. Maio (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on the psychology of attitudes (pp. 35–56). London: Psychology Press. Haddock, G., Zanna, M. P., & Esses, V. M. (1994). The (limited) role of trait–based stereotypes in predicting attitudes toward Native Peoples. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 83–106. 468 HUSKINSON AND HADDOCK Huskinson, T. L. H., & Haddock, G. (2004). Assessing individual differences in attitude structure: Variance in the chronic reliance on affective and cognitive information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 82–90. Huskinson, T. L. H., & Haddock, G. (2006). Attitude structure influences the clustering of affective and cognitive information. Manuscript in preparation. Jarvis, W. B. G., & Petty, R. E. (1996). The need to evaluate. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 172–194. Lazarus, R. S. (1984). On the primacy of cognition. American Psychologist, 39, 124–129. Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (1993). Affect, cognition, and awareness: Affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 723–739. Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta–analytic procedures for social research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Trafimow, D., & Sheeran, P. (1998). Some tests of the distinction between cognitive and affective beliefs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 378–397. Verplanken, B., Hofstee, G., & Janssen, H. J. W. (1998). Accessibility of affective versus cognitive components of attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 23–35. Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151–175. Zanna, M. P., & Rempel, J. K. (1988). Attitudes: A new look at an old concept. In D. Bar–Tal & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), The social psychology of knowledge (pp. 315–334). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.