Does Shareholder Voting on Acquisitions Matter?

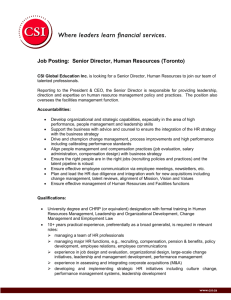

advertisement