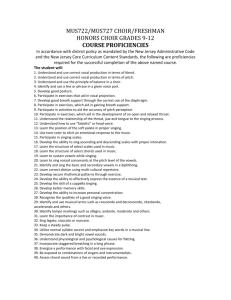

Case study on the impact of IOE research Music Education

advertisement

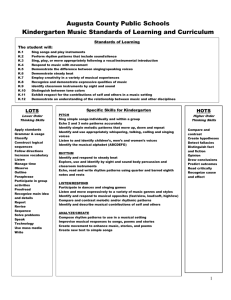

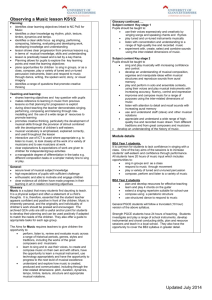

Case study on the impact of IOE research Music Education January 2011 Case study on the impact of IOE research Music Education “Evidence suggests that learning an instrument can improve numeracy, literacy and behaviour. But more than that, it is simply unfair that the joy of musical discovery should be the preserve of those whose parents can afford it.” Michael Gove, Education Secretary, speaking at the launch of the Henley Review of Music Education, September 24, 2010. Who carries out music research at the IOE? The Institute of Education has almost 20 music education specialists – the largest group of music education researchers working in the same institution in the UK. They are all associated with the IOE’s International Music Education Research Centre: (http://imerc.org), which was established in 2005. Who provides the funding? The iMerc researchers have attracted funding from major UK research councils, the European Community, government departments, local authorities, leading charities such as the Paul Hamlyn and the Esmée Fairbairn foundations, and other charitable bodies that promote music. Introduction Researchers at the Institute of Education have had a very substantial effect on what is taught in the music classroom – and how it is taught. Like other researchers, they only occasionally exert direct influence over the policymakers who shape the music education curriculum. Most music education studies are not produced for a policy audience. Even so, music research can help decision-makers to evaluate the range of choices before them. It can also, crucially, help to create, bolster or challenge the assumptions that underlie national and local policy decisions. A recent example is offered by the important independent review of music education in England that the coalition government launched in September 2010. Education Secretary Michael Gove told the review chairman, Darren Henley, managing director of Classic FM, that he should make several key assumptions as he set out to gather evidence. One was that the “secondary benefits of a quality music education are those of increased self-esteem and aspirations; improved behaviour and social skills; and improved academic attainment in areas such as numeracy, literacy and language.1 There is evidence that music and cultural activity can further not only the education and cultural agendas but also the aspirations for the Big Society”. Where did the evidence supporting this assumption come from? Much of it was, in fact, derived from empirical studies in the UK and Italy under the leadership of Professor Graham Welch, chair of 1 The IOE’s music research has done much to publicise the physical, psychological and cognitive benefits of singing or learning to play an instrument. Other research led by Professor Lucy Green has helped to popularise informal approaches to music education that are similar to the ways in which rock musicians learn their craft. Music Education music education at the IOE, and from a major review of music research that was compiled by his colleague, Professor Sue Hallam. The then Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) commissioned Professor Hallam’s review to mark the start of Tune In – Year of Music, which began in September 2009. Her paper, The power of music: its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people (http://www.ioe.ac.uk/ Year_of_Music.pdf ) documents the effects that a child’s active engagement in music can have on their: teaching and learning3 and is having a huge impact on classroom practice, as will be explained later in this case study. • Music research at the IOE has also served to debunk some myths that have gained credence in recent years, such as the suggestion that listening to Mozart improves children’s cognitive performance. In fact, some pop songs can have a more beneficial effect on pupils’ schoolwork, as Professor Hallam has pointed out.5 • • • • • perceptual, language and literacy skills numeracy intellectual development general attainment and creativity personal and social development, and physical development, health and well-being. The paper followed an earlier research review for parents and teachers on the importance of music by Professor Welch and Pauline Adams that had been commissioned by the British Educational Research Association (BERA) with support from the UK Government. This review was launched at the House of Commons in October 2003.2 Key themes of the Institute’s music research The IOE’s own music research has also done much to publicise the physical, psychological and cognitive benefits of singing or learning to play an instrument. It has emphasised the value of music in its own right too. Another very important strand of IOE research, led by Professor Lucy Green, has helped to popularise informal approaches to music education that are similar to the ways in which rock musicians learn their craft. Her work challenges traditional views of music A key message from several IOE studies is that musical development is possible for everyone, not just a ‘talented’ minority.4 “For example, it is not a case of ‘can sing/can’t sing’. It’s a continuum,” says Professor Welch. “Everybody can sing. The term ‘tone deaf’ should be confined to the very small number of people who have some form of neurological disorder in the processing of sound.” Her research into children’s choice of musical instruments has raised questions about gender stereotyping too6. It confirmed that girls tend to play the harp, flute, piccolo, clarinet, oboe and violin while boys are far more likely to choose the electric guitar, bass guitar, tuba and trombone7. Singlesex ensembles could help to bridge the divide, Professor Hallam and her colleagues concluded. Among the other topics being investigated by the IOE’s music researchers are: • • • • • the place and use of music technology in music education the professional development of musicians music teacher education motivation and self-perceptions of conservatoire students, and effective choral education and choral leadership. 2 Case study on the impact of IOE research Major IOE music research projects The projects under way include: Sing Up The Government’s £40 million fouryear (2007–11) singing programme for primary schools in England is being evaluated by Professor Welch, Dr Evangelos Himonides, Dr Jo Saunders and Dr Ioulia Papageorgi.8 Sing Up aims to ensure that primary children experience high-quality singing on a daily basis. The IOE team undertook a baseline audit of singing in randomly selected schools and has used this data to measure the programme’s impact. Over the first three years of Sing Up, this evaluation project took the researchers to 177 English schools. They have assessed the individual singing development of nearly 10,000 pupils, mainly aged 7 to 10, and have noted children’s attitudes to singing, in and out of school. 3 They found that children who have taken part in Sing Up are, on average, two years ahead in their singing development, compared to those not involved in the programme. The Sing Up evaluation has also confirmed that older children – including boys – can develop much more positive attitudes to singing if they: • • have expert role models, whether adult or child, such as those provided in the Singing Playgrounds (http:// www.excathedra.co.uk/) and Chorister Outreach programmes (http://www.choirschools.org. uk/2csahtml/outreach.htm), and experience a rich musical repertoire, including singing games and opportunities for performance, which is interwoven into the school’s educational culture. The IOE evaluation has found that better singers tend to have a more positive view of themselves and a stronger sense of social inclusion, a IOE researchers found that children taking part in the Government programme Sing Up are, on average, two years ahead in their singing development. Music Education finding that is supported by research conducted for the Italian government.9 Responses from more than 1,000 teachers and community musicians involved in Sing Up suggest that their confidence in their own singing and teaching has also improved as a direct result of the professional development offered by the programme. Musical Futures The ‘Informal learning in the music classroom’ study that a team led by Professor Lucy Green undertook in partnership with Hertfordshire County Council is also making a very important contribution to music education. This pathfinder project formed part of the successful Musical Futures initiative funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and the DCSF (now the Department for Education).10 Professor Green developed and evaluated radical new teaching and learning strategies for 11 to 14-yearolds that were drawn from the informal learning practices of popular musicians. Whilst popular music has been a part of curriculum content for over 30 years, classroom pedagogy continued to use models that were suited for classical music. By basing itself on the very different ways in which popular musicians learn, Lucy Green’s work has brought a refreshingly new method of teaching into the classroom. Pupils taking part in the Hertfordshire study directed their own learning in small friendship groups, selecting their music and attempting to play it by ear from the recording. Teachers initially stood back and observed, then acted as guides and musical models rather than instructors. Pupils later composed music, performed in bands with community musicians, and applied the learning strategies they had acquired to classical music, again, under the guidance of their teachers. The five-year research-anddevelopment phase of the work ended in 2007, but the implementation of the strategies within classrooms is growing all the time. More than 1,000 schools are adopting the informal learning model (see the Impact section of this case study). Musical Futures is being evaluated by another team of IOE researchers led by Professor Hallam and Dr Andrea Creech. An evaluation they carried out in 2008 established how many schools had taken up Musical Futures and what they were doing. Their second evaluation, which will continue until 2011, is a longitudinal investigation of how the project is evolving in six schools. Sounds of Intent Graham Welch is leading the Sounds of Intent programme with Professor Adam Ockelford, a Visiting Research Fellow and Professor of Music at Roehampton University. This programme is investigating and promoting the musical development of children and young people with severe, or profound and multiple learning difficulties (until relatively recently, only 5 per cent of this group were receiving music therapy). The researchers have devised a new way of mapping musical development for such children11 and their methods have been made available to the whole special education sector in the UK and internationally through a new dedicated website, designed by Dr Evangelos Himonides. This project was set up in 2002 by the IOE in collaboration with the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), building on an earlier national survey. The latest 15-month extension to the programme is being funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. The project team includes Sally-Anne Zimmermann from RNIB and Dr Angela Vogiatzoglou (Roehampton). New Dynamics of Ageing (NDA) music project This music project is part of the largest and most ambitious research programme on ageing ever mounted in 4 Case study on the impact of IOE research this country. The programme is a unique collaboration between five UK research councils.12 The NDA music project being led by researchers at the Institute of Education is examining whether older people’s participation in music-making, particularly in community settings, can improve their well-being. It is also trying to establish whether there are spin-off benefits for families and residential communities when older people become actively involved in making music. The study is being carried out by four IOE researchers – Sue Hallam, Andrea Creech, Maria Varvarigou and Hilary McQueen – and involves three-casestudy sites: • • • The Sage Gateshead, where more than 500 people take part in weekly music activities such as singing, African drumming, and playing guitars, recorders, steel pans and ukuleles. The Guildhall Connect Project, which runs community music projects in East London with people from a wide range of backgrounds, ages and experiences. It offers everything from classical to popular music, western and non-western genres. The Music Department of the Westminster Adult Education Services, which provides community music activities for older people. Courses are offered in not only singing and playing instruments, but sound engineering and composing. Interviews, focus groups and observations have been carried out at each case-study site. Questionnaires have also been completed by 350 older people participating in musical activities and by a control group of just over 100 people who are taking part in non-musical activities. Most of the participants are aged between 60 and 80. Preliminary findings suggest that levels of well-being are higher amongst 5 the music participants than amongst the control group. Usability of Music for the Social Inclusion of Children (UMSIC) The UMSIC project (2008–2011) is supporting children’s social inclusion through music. It is doing this by developing a hand-held JamMo (jamming mobile) which encourages children to communicate musically using mobile phones. The JamMo enables them to compose songs, then create new versions of the song using virtual instruments. As it has a karaoke function, a child can also listen to a song, sing along, save the result and share it with a teacher, friend or relative. The project, which also aims to foster children’s creative musical development, is targeted at both pre-school youngsters (3–5 years) and primary school pupils (6–12 years). Whilst intended to be suitable for all children, the JamMo is primarily designed to help two groups at high risk of marginalisation: (i) children with social, attention or emotional disorders and (ii) migrant children. The research is funded by the European Commission (EC) and involves a network of researchers from universities in Finland, Switzerland and the UK, as well as software specialists in Greece and the phone company Nokia. During the first two years of the project, its London team (Professor Graham Welch, Ross Purves and Dr Tiija Rinta) has researched aspects of children’s social inclusion and initiated pilot studies in primary schools to evaluate the emerging software packages. The latest report from the EC (October 2010) praises the quality of these pilot studies, and says that the IOE team and its European colleagues are making a “state-of-the-art contribution” to this research field. One project is developing mobile phones that allow children to compose music. The aim is to help those at risk of social marginalisation. Music Education When you sing, you breathe in a different way ... there’s a tendency to increase the airflow so your blood is more oxygenated. Professor Graham Welch How the research messages are promoted Academic writing The IOE’s music researchers have written hundreds of academic journal articles, two substantial single-authored books, and many other shorter works and edited books in recent years. Some have been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Swedish, Polish, Greek, Japanese, Korean or Chinese. Media articles and interviews Leading IOE music researchers, such as Professors Welch, Hallam and Green, have written about their research in books and magazines aimed at a general readership. Their work has also featured in many newspaper and web articles. Much of this coverage has been triggered by their writings on the physical and psychological benefits of music-making.13 In May 2009, for example, the Daily Telegraph quoted Professor Welch as saying: “When you sing, you breathe in a different way so you use more of your total lung volume. This means there’s a tendency to increase the airflow so your blood is more oxygenated.” Professor Hallam has also spoken about her music research findings on radio and television on many occasions and has been interviewed on Music Matters, Radio 3’s flagship classical music magazine programme. A BBC1 programme on the informal learning model based on Professor Green’s research was broadcast in 2009. Several newspapers and magazines have also reported and commented on her work. Conference presentations IOE researchers disseminate their findings via conference and seminar presentations in the UK and abroad. Professors Welch, Green and Hallam and Dr Colin Durrant, an authority on choral conducting and singing, have been invited to give keynote lectures about their work at universities and conferences in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia and the Americas. Teacher education Research findings are also disseminated via teacher education at the Institute. The IOE offers an MA in Music Education and has the largest number of graduate students in music education in Europe. Many of its doctoral students work part-time on funded projects to extend their research knowledge and understanding. 6 Case study on the impact of IOE research Impact of the research Musical Futures Some teachers were sceptical when Musical Futures brought informal learning to their classrooms. However, their concerns were quickly dispelled as soon as they started the work, and the approach now has the enthusiastic support of teachers as well as pupils.14 The project has been recommended by the Music Manifesto,15 and the Department for Education has made it available to all schools through its website. It has also been endorsed by the singer-songwriter, Sting, the global patron of the initiative. Over the past few years, the number of secondary schools adopting Musical Futures has risen from fewer than 60 to more than 1,000. The ongoing evaluation16 by Professor Hallam and Dr Andrea Creech has found that the introduction of the Musical Futures approach prompted a sharp rise in enrolment for GCSE music courses.17 It is also said to have had a positive effect on pupils’ behaviour and motivation levels and boosted their confidence in their music-making abilities. In September 2008 Musical Futures launched a network of ‘champion schools’. These schools have developed the initiative and now devise and deliver free training for music teachers.18 Musical Futures has also started to spread overseas. Schools in Australia, for example, are now introducing the programme as part of a state-by-state roll-out, beginning with 10 pilot schools in Victoria. The work has also spread to Brazil, where a network of schools co-ordinated by the University of Brasilia is adopting the Musical Futures strategies. The Open University of Brazil is also piloting a teacher-training unit promoting the strategies. In the United States, this groundbreaking approach to music education has been adopted by programmes such as ‘Little Kids Rock’ (www.littlekidsrock.org) and by the Informal Learning Project conducted by the Westminster Choir College of Rider University, New Jersey. 7 Lucy Green’s writing on the benefits of the informal approach to school music-making had, however, begun to make an impact in South America and elsewhere even before Musical Futures got under way.19 Her influential 2001 book, How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead For Music Education, inspired a collaborative research project between two Brazilian universities, the Federal University of Bahia and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Her work has also been widely discussed by music educationists in the US. A symposium on her research was held at the American Educational Research Association conference in 2008 and the papers presented were later published in a special edition of a US journal, Visions of Research in Music Education.20 Other special issues on her work have been published by the US journal, Action, Criticism and Theory in Music Education, and the British Journal of Music Education. Sing Up Although Sing Up is undoubtedly a collective enterprise, Graham Welch is recognised as one of its architects. The programme, launched in late 2007, was partly shaped by the advice he offered at the planning stage, and Professor Welch was subsequently appointed as its main research adviser. His team’s evaluation findings have fed into the development of Sing Up, which has been adopted by more than 85 per cent of England’s 17,000-plus maintained primary schools. Professor Welch’s contribution has been acknowledged by Baz Chapman, the programme’s director: “We believe that Sing Up’s research needs have been too complex and specialist to be carried out by any but a very few researchers. This is, for us, the ultimate research partnership.” Year of Music research Professor Hallam’s review of research into the cognitive, physical and psychological benefits of music was referred to by Ed Balls, the then Music Education Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, at the launch of the first National Year of Music in September 2009. The ex-Schools Minister Diana Johnson also cited Professor Hallam’s review at the launch event: “Research from the Institute of Education tells us that involvement with music can have a huge impact on the development of young people, and that it can even promote social cohesion and better behaviour. And because we know that learning to play an instrument can improve both reading and writing, it is right that music should play an important role in school life, and beyond.” As noted at the beginning of this case study, the key findings of Professor Hallam’s research review have also been accepted by leading members of the coalition government elected in 2010. Professor Hallam’s research digest has been posted on the websites of several national organisations, such as the Training and Development Agency for Schools and the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. She has also been commissioned to write a number of articles based on her research review. One was featured in an issue of Music Journal, the monthly magazine of the Incorporated Society of Musicians.21 Increased investment in music education IOE surveys of local authority music services in 200522 and 200723 in England have also helped to provide the rationale for increased government investment in music education in recent years. A document published by the previous Labour government, “Music education and the music grant (Standards Fund 1.11)”,24 acknowledges the importance of the two survey reports by Professor Hallam and her colleagues. “Government has learned from the pilot programmes and from the National Survey reports in 2005 and 2007,” it says. “The key factors supporting the programmes and the barriers to widening participation have been identified.” The document then goes on to list the principal actions taken to address the issues highlighted by the pilots and the IOE surveys. These include: • • • funding changes designed to encourage local authorities to prioritise spending on instrumental and vocal programmes at Key Stage 2 (ages 7 to 11), an extra £40 million made available to ensure pupils have access to the full range of instruments, and high quality continuing professional development, provided free of charge. Child choristers Graham Welch has researched and written extensively on child choristers.25 Several studies he conducted with colleagues found that even expert listeners could seldom tell the difference between all-boys, allgirls and mixed choirs. This research also concluded that sounds that are perceived as ‘masculine’ are often made by choirs trained by men whilst ‘feminine’ sounds are generated by choirs trained by women. These findings strengthened the argument that the introduction of girls into cathedral choirs would have no effect on the choral tone produced. Music teaching in primary schools Research led by Sue Hallam showed that there was great variability in the quality of music teaching and singing in primary schools.26 It also confirmed that many trainee primary teachers lacked confidence in their ability to teach music.27 As a result of these findings, the EMI Music Sound Foundation, a leading music education charity, asked Professor Hallam and her colleagues to carry out a further survey that provided additional insights into the problem. The survey found, for example, that almost four in ten primary teachers could not read music and some did not even feel confident enough to sing in front of a class of four-year8 Case study on the impact of IOE research 9 olds. However, the IOE research also revealed that even a day of training could dramatically improve teachers’ confidence and ability to teach music.28 Four months after the training day, 98 per cent of the teachers agreed that it had improved their music teaching, and that pupils were enjoying music lessons more. EMI Music Sound Foundation is now rolling out the training programme to a further 30 schools. on special schools. It is helping to change perceptions about the musical development that is possible with children and young people who have complex needs. The Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency, inspectors and schools have all expressed keen interest in this project. Ten schools in the Midlands and South of England are working closely with the research team. Special educational needs Sounds of Intent, the joint IOE, Roehampton University and RNIB project, is having a substantial impact Local authority music services and exam bodies The influence of IOE research can be detected in many local authority Music Education documents. The introduction to the booklet setting out the Devon Music Service Strategy for 2005–2009 begins with one of Graham Welch’s characteristic comments: “Everyone has the capacity to be uniquely musical but the development of our musicality and the realisation of our potential are shaped by experience.”29 The Devon document responds by adding: “Our mission therefore should be simple: to create frequent high quality musical experiences for all learners.” Exam bodies have cited the Institute’s music studies too. For example, the Scottish Qualifications Authority uses a quotation from Professor Hallam to help explain the context for its Higher National Unit on Music and Cultural Policy: “Music is powerful at the level of the social group because it facilitates communication which goes beyond words, induces shared emotional reactions and supports the development of the group identity.”30 Health IOE research that has drawn attention to the cardiovascular benefits of singing has been heeded by Heart Research UK. It organised a national singing week in December 2009 and decided to repeat the exercise in December 2010. The charity cited Professor Welch’s research in its event publicity and quoted some of his main conclusions on the health benefits of singing.31 A second singing initiative, Learn to Sing, supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, has used similar comments from Graham Welch in its recent publicity (http://www. choiroftheyear.co.uk/press-release4. htm). International reputation The international regard for the IOE’s music research is indicated by the fact that Professor Welch is president of the world body for music education, the International Society for Music Education. He is only the second English person in more than 50 years to be elected to this post. Professor Welch is also chair of another international organisation, the Society for Education, Music and Psychology Research (SEMPRE) and co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Music Education and Oxford Handbook of Singing. Professor Hallam, is a leading expert in the psychology of music and edited SEMPRE’s journal from 2001 to 2007. Sue Hallam is also co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology. Governments and institutions around the world have consequently sought the advice of IOE music researchers. Sue Hallam has provided advice on the development and protection of music services in Australia and the US. Graham Welch has been consulted about children’s singing, teacher development and the evaluation of music initiatives by the Italian Ministry of Education, the National Center for Voice and Speech in Colorado, US, the Swedish Voice Research Centre, the British Council in the Ukraine, the South African National Research Foundation and the Ministry for Education and Youth in the United Arab Emirates. As noted earlier, Lucy Green’s work on informal music education, which underpinned the Musical Futures programme, has also proved influential around the world. She is an international authority not only in informal music learning practices, but also innovative ways in which to adopt and adapt these for the classroom. She sits on the editorial boards of no fewer than 10 academic journals, two of which are published in Brazil, one in Greece, one in Australia, and another in SouthEast Asia. The future IOE music researchers will be reporting on their latest findings at conferences around the world. Graham Welch and his team intend to continue their research into the wider benefits of singing. They are aiming to identify the key principles of high-quality singing education, based on the evidence gathered. This 10 Case study on the impact of IOE research work will benefit from the findings of new collaborative research with neuroscientists at Birkbeck College and the University of Sheffield. Additionally, he and his co-researchers on the Sounds of Intent project are using their new funding to ensure that the world’s first interactive website to support the music work of special school teachers has a global reach, with an initial pilot in Pakistan. Colin Durrant is continuing his research into singing and choral conducting while Sue Hallam and her co-researchers will be undertaking their evaluation of the long-term impact of Musical Futures, and their New Dynamics of Ageing research into the benefits of music-making in later life. However, they are also planning to assess the effect that active engagement with music can have at the other end of the life cycle – the ‘early years’ – and they will be mounting 11 another study of instrumental tuition at all levels, from beginners to professionals. Lucy Green is carrying out research, funded by Esmée Fairbairn, into how informal music learning practices can be transferred from the classroom to one-to-one instrumental lessons. This research has already generated some new concepts concerning musical learning styles, which will be discussed in an article in a major journal (Psychology of Music) next year. Professor Green has also been invited to contribute a chapter on this work to a book edited by Scandinavian academics. It therefore seems certain that IOE researchers will continue to have a significant influence on music education not only in this country, but around the world, in the years ahead. Further Reading / Notes Further Reading Notes DURRANT, C. (2003). Choral Conducting: Philosophy and Practice. New York: Routledge. GREEN, L. (2008). Music, Informal Learning and the School: A New Classroom Pedagogy. London and New York: Ashgate Press. 1 Lord Hill of Oareford, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Education, made a similar statement in the House of Lords on October 5, 2010. See http:// www.theyworkforyou.com/wrans/?id=2010-1005a.1.0&s=music HALLAM, S., CROSS, I. and THAUT, M. (eds) (2008). Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2 WELCH, G.F. and ADAMS, P. (2003). ‘How is music learning celebrated and developed?’ [BERA Professional User Research Review]. Southwell, Notts: British Educational Research Association. [pp24] [ISBN 0 946671 22 2] http://www.bera.ac.uk/publications/ reviews/ HALLAM, S. and CREECH, A. (eds) (July 2010). Music education in the 21st Century in the United Kingdom: Achievements, analysis and aspirations. London: Institute of Education, University of London. WELCH, G.F., PURVES, R., HARGREAVES, D. and MARSHALL, N. (2010). ‘Early career challenges in secondary school music teaching’. British Educational Research Journal. First published online 26 March 2010, DOI: 10.1080/01411921003596903. WELCH, G. F. and PAPAGEORGI, I. (2008). ‘Investigating Musical Performance: How do musicians deepen and develop their learning about performance?’ ESRC/TLRP: Teaching and Learning Research Briefing 61; see also http://www.tlrp.org/proj/Welch.html for an extensive list of publications related to the Investigating Musical Performance project. 3 GREEN, L. (2001). How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead For Music Education. London and New York: Ashgate Press. 4 WELCH, G.F. (2001). The misunderstanding of music. London: University of London Institute of Education. [pp 42] [ISBN 0-85473-660-3]; WELCH, G.F.(2005). We are musical. International Journal of Music Education, 23(2), 117-120. 5 HALLAM, S. (2004). ‘The Mozart Effect’, keynote presentation to Thurrock Schools’ Music Conference, Thurrock, Essex, 18th March. 6 This work built on earlier research by other music specialists, such as Professor Green, author of the only book to be published on gender and music education: GREEN, L. (1997). Music, Gender, Education. Cambridge University Press. 7 HALLAM, S., ROGERS, L. and CREECH, A. (2008) ‘Gender differences in musical instrument choice’, International Journal of Music Education, Vol. 26(1). 8 WELCH, G.F., HIMONIDES, E., SAUNDERS, J., PAPAGEORGI, I., VRAKA, M., PRETI, C., and STEPHENS, C. (2010). ‘Researching the impact of the National Singing Programme Sing Up in England’. Institute of Education, University of London. 9 WELCH, G.F., PRETI, C., and HIMONIDES, E. (2009). Progetto Musica Regione Emilia-Romagna: A researchbased evaluation. London: International Music Education Research Centre. 10 The pilot work for the informal learning strand was funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. 11 WELCH, G.F., OCKELFORD, A., ZIMMERMANN, S-A., HIMONIDES, E., and CARTER, F-C. (2008). ‘Sounds of Intent’. London: Institute of Education; WELCH, G.F., OCKELFORD, A., CARTER, F-C., ZIMMERMANN, S-A., and HIMONDES, E. (2009). ‘Sounds of Intent: Mapping musical behaviour and development in children and young people with complex needs’. Psychology i Notes of Music, 37(3), 348-370; OCKELFORD, A., WELCH, G.F., JEWELL-GORE, L., CHENG, E., VOGIATZOGLOU, A., and HIMONDES, E. (in press). ‘Sounds of Intent, Phase 2: Approaches to the quantification musicdevelopmental data pertaining to children with complex needs’. European Journal of Special Education. 12 Further information about the NDA programme can be found at www.newdynamics.group.shef.ac.uk 25 WELCH, G.F. and HOWARD, D.M. (2002). ‘Gendered Voice in the Cathedral Choir’. Psychology of Music, 30, 102-120; WELCH, G.F. (in press). Culture and gender in a cathedral music context: An activity theory exploration. In M. Barrett (Ed.), A Cultural Psychology of Music Education. New York: Oxford University Press. 13 Graham Welch can be heard speaking about the health benefits of singing in a Radio 4 Today programme broadcast in April 2009. news.bbc.co.uk/ today/hi/today/newsid_8003000/8003719.stm 26 HALLAM, S., ROGERS, L., CREECH, A. and PRETI, C. (2005). ‘Evaluation of a Voices Foundation Primer in primary schools’. Research Report. London: Department for Education and Skills. 14 A case study illustrating the benefits of Musical Futures can be found at curriculum.qcda.gov.uk/ key-stages-3-and-4/case_studies/casestudieslibrary/ case-studies/Personalised_learning_breathes_life_ into_music.aspx 27 HALLAM, S., BURNARD, P., ROBERTSON, A., SALEH, C., DAVIES, V., ROGERS, L. and KOKATSAKI, D. (2009). ‘Trainee primary school teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness in teaching music’. Music Education Research, 11(2), 221–240. 15 Further information about the Music Manifesto campaign is available from www.musicmanifesto. co.uk/ 28 HALLAM, S., CREECH, A., RINTA, T. and SHAVE, K. (2009) EMI Music Sound Foundation: Evaluation of the impact of additional training in the delivery of music at Key Stage 1, Institute of Education, University of London. 16 HALLAM, S., CREECH, A., SANDFORD, C., RINTA, T. and SHAVE, K. (2008). Survey of Musical Futures: a report from Institute of Education, University of London for the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Project Report. 17 The evaluation team has, however, noted that GCSE music may not be appropriate for all pupils involved in informal music-making. Several schools following the Musical Futures programme have switched to BTEC examinations. 18 Information on the training programme can be found at www.musicalfutures.org.uk/training 19 HENTSCHKE, L. and MARTINEZ, I. (2004). Mapping Music Education Research in Brazil and Argentina: The British Impact, Psychology of Music; 32; 357. 20 This edition of the journal can be found at wwwusr.rider.edu/~vrme/ 21 ‘How powerful is music?’ www.ism.org/news_ campaigns/article/how_powerful_is_music/ 22 HALLAM, S., ROGERS, L., and CREECH, A. (2005). Survey of Local Authority Music Services 2005. Research Report 700. London: Department for Education and Skills. 23 HALLAM, S., CREECH, A., ROGERS, L. and PAPAGEORGI, I. (2007). Survey of Instrumental Music Services 2007. London: DfES. ii 24 www.ks2music.org.uk/do_download. asp?did=29568 29 ‘This is our music: Devon Music Service Strategy for 2005–2009’ www.devon.gov.uk/thisisourmusicjune05.pdf 30 The SQA document can be found at www.sqa.org. uk/files/hn/DDR2M34.pdf 31 www.heartresearch.org.uk/Singing_is_good_for_ you.htm