Gang Wars - Justice Education Society of BC

advertisement

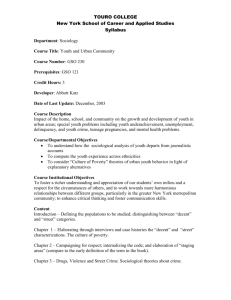

A10 || WESTCOASTNEWS BREAKING NEWS: VANCOUVERSUN.COM | SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2009 | ✰ WEEKEND EXTRA The evolution of organized crime Many criminal groups have become increasingly sophisticated, widespread — and violent BY KIM BOLAN VANCOUVER SUN B rianna Kinnear was just 22 when she was gunned down in a borrowed truck on the side of a Port Coquitlam street Feb. 2. Kevin LeClair was a little older at 26 when he was sprayed with automatic gunfire in a busy mall parking lot four days later. And Betty Yan was 39 when she was found shot to death in a grey Mercedes at a dark industrial Richmond strip mall April 15. All three were targeted for death because of their rung in the hierarchy of one of B.C.’s 135 crime groups. Kinnear worked on the front lines selling drugs in a street crew operating throughout the Tri-Cities. LeClair was mid-level, a member of the notorious Red Scorpion gang, who ran more than a dozen drug lines. And Yan was one of those rarer hits of someone connected to the top-echelon crime groups in B.C., in her case the Big Circle Boys. With billions of dollars a year at stake and an unprecedented number of groups vying for territory and profits, police and academics say there is an increasing sophistication in the way crime groups do business here. At the same time, there has been a record number of gangland slayings, most of them of mid-level or front-line drug dealers. “It is still a very diverse illicit market per se,” said Supt. Brian Cantera, who heads the RCMP’s regional drug section. “It has still got the potential for huge profits and there are those who are fighting over those profits. “If you take a look at the level of violence we’ve seen, there are a lot more gang-related homicides or mid-level drug trafficking homicides than we’ve seen in the past,” Cantera said. It is rare for someone like Yan, a loan shark with tentacles deep into organized crime groups, to be targeted. More commonly, those sacrificed in the war are front-line soldiers like Kinnear or gang members like LeClair, possibly targeted because of his association with gangsters such as Jonathan, Jarrod and Jamie Bacon. Cantera said it is difficult to quantify exactly how much money is passing through B.C. crime groups every year. One estimate has pegged the province’s marijuana industry alone to be worth $7 billion annually. ‘A need for hierarchy’ Criminologist Stephen Schneider, who has just released a book on the history of organized crime in Canada, says there has been a shift in how crime groups operate in B.C. and other provinces. “There has definitely been an historic evolution in all aspects of organized crime,” Schneider said. “Sophistication. Power. Wealth. Reach. “As the groups have become more powerful and more widespread, just like a legitimate corporation, there is a need for hierarchy. So you have seen, as the groups evolve, increases in hierarchy.” In B.C., that hierarchical structure looks a pyramid with groups such as the Hells Angels, the Mafia, the Big Circle Boys and other Asian triads at the top. They have long historic roots, international connections, sophisticated structures, exclusive memberships and are often dealing with tens of millions of dollars a year. Sometimes they are directly linked to mid-level groups such as the Red Scorpions, the Independent Soldiers and the United Nations — all brand-name gangs that morphed out of smaller groups involved in the drug trade over the last decade. The mid-level groups range in size and sophistication. The UN, for example, has about 100 members and more entrenched indoctrination, much like the top-level groups. GANG WORLD High level: •Top-echelon crime groups are highly structured with long roots • Exclusive membership in organizations such as the Hells Angels and Asian triads • International links • Huge profits,sometimes laundered though legitimate businesses HIGH level: 1 dead Crime groups in B.C. range from highly structured organizations such as the Hells Angels to loosely affiliated street gangs and drug dealers.All fall into one of three levels:low,mid and high. Organized crime groups operating in B.C.identified by category 2003 Asian 8 Eastern European 3 Hispanic 0 Indo-Canadian 5 Independent 11 Middle Eastern 0 Outlaw Motorcycle 10 Street gangs 0 Italian 14 TOTAL 51 2004 14 6 3 10 11 7 26 1 4 2005 10 9 1 10 35 5 29 5 4 2006 17 8 0 10 42 3 36 4 4 2007 21 3 3 11 49 5 33 3 1 82 108 124 129 2008 2009 24 24 4 4 3 3 11 11 49 51 5 5 33 33 3 3 1 1 133 Mid level: • Street-level identity, sometimes with a name and logo such as the UN and Red Scorpions • Connections to the top groups and street crews • Engaged in most violence with rivals over territory and personal disputes,with their street-level crews the main victims • Could have anywhere from a dozen to 100 members • Good profits often used on luxury purchases like cars MID level: 4 dead 135 Source:RCMP STREET level: 16 dead Street level: Graphic:Maggie Wong, Vancouver Sun When police raided the houses of leader Clay Roueche last year, they found a score sheet indicating almost $900,000 in drug transactions. The gang bought two aircraft to smuggle drugs across the border, a crime to which Roueche has pleaded guilty in the U.S. Roueche also boasted in bugged conversations to having his own contacts in Colombia and other source countries. The Scorpions, started in a youth detention centre nine years ago, number no more than about 25, says Sgt. Shinder Kirk, of the B.C. Integrated Gang Task Force. Yet the Scorpions have been linked to some of the worst gang violence in B.C. history, including the slaughter of six people in a Surrey high-rise in October 2007. Mid-level gangs might have an annual cash flow ranging from a few hundred thousand to millions of dollars. Crews like Kinnear’s can be independent operators or tied vertically to a gang. But as Abbotsford Police Chief Bob Rich said last month, socalled street-level dealers get linked by rivals to the gang with which they do business, regardless of whether the connection is real or perceived. “Any young person out there now — because of the potential for retaliation and the confusion that exists over who is associated with who — is at risk if they are involved in the drug trade,” Rich warned. Front-line drug crews are earning thousands to tens of thousands a month, but are also • More loosely structured than above • Smaller in number (from three to 10 people) • Can be independent buying drugs from different mid-level gangs • Can be directly affiliated with mid-level or even top-level gangs • Most likely victims of violence, and earn the least amount of money the ones taking most of the risk, whether it is of arrest or violent underworld retaliation. Kirk said the top-level crime groups are deliberately insulating themselves “from not only the general day-to-day business, but from the dirty business. “They still profit from the illegal activities of those at the lower level.” The mid-level gangs “work horizontally with other groups at the same level, but also vertically within the triangle.” Some of the front-line and mid-level gangs were actually set up by top groups, Kirk said. “You’ve got puppet clubs that may be newer on the scene than some of the more recognized puppet clubs that have been around for a long time. So that is more insulation and evolution in the sense of getting someone else to do your dirty work.” Some mid-level groups or even unknown “freelancers” are involved in cross-border smuggling, Kirk said, because the profits are so high if they can find a mode of transportation and a route. Activity straddles border Last month, B.C. tow truck driver Robert Fox was arrested near Sacramento, Calif. with $7 million worth of ecstasy and more than $400,000 cash. He has no criminal record here, but is now facing serious U.S. charges. “There is a capacity for an individual or a group at any level to cement international ties into the U.S. or overseas,” Kirk said. “You can have a subcontractor who develops a smuggling route and was contracting his services out to individuals who have product. He would then guarantee delivery or make arrangements for delivery.” B.C. drug gangs learned from the huge Colombian cartels of the 1990s how to create “corporate hierarchal structures,” Schneider said. But the Colombians wanted to control all aspects of the drug deals from production to purchase to delivery, while new crime groups hire specialists at different stages, Kirk said. “One of the trends in organized crime over the last 20 years has been less self-contained hierarchical groups that work exclusively on their own and towards incredible networking of small groups, of larger groups, of individuals, and that’s why the problem has proliferated in that you have this cooperation,” he said. “It is almost like you have specialization and division of labour, where one group specializes in providing the product, the other in transporting it, the other in marketing it at the street level, another wholesaling it.” When Metro Vancouver’s Rob Shannon was sentenced to 20 years for his role in a multimillion-dollar cross-border drug trafficking ring linked to the Hells Angels, Chief U.S. District Judge Robert Lasnik did not ac- cept the prosecution’s position that Shannon was the overall crime boss. Lasnik did accept that Shannon headed the transport division of the criminal enterprise, specializing in creative crossborder smuggling modes, and slapped him with a 20-year sentence. That makes sense, according to Schneider, whose book Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada, was recently published. “We are seeing these very large criminal conspiracies but again, they are operating on a network basis and that allows for more fluidity, flexibility, and it also is strategic in that if one cell or partner gets busted, there is less chance the police can go to another cell because the relationship is not as strong.” The fluidity, ever-changing allegiances and networking, coupled with increasing sophistication of the schemes, makes the job even tougher for law enforcement agencies, as well as the courts, Schneider said. “Our criminal justice system now simply cannot cope with the scope of the problem — the level of sophistication. Our prosecutorial services are just cut to the bone provincially and federally and they cannot take on sophisticated cases or large cases, and that’s why you see so many of them being plea-bargained.” New laws called for Police have had to strategize and to some degree, mirror the structure of the criminal hierarchy, having different agencies GANG WARS: JUSTICE IN OUR TIMES A special Vancouver Sun five-day series which looks at the hierarchy of B.C.’s 135 crime groups. TODAY: A guide to gang structure in B.C. Monday,June 8:An overview of the gang problem in the U.S.,Mexico and Central America,and the links to B.C. Tuesday,June 9:How police and prosecutors tackle gangs in B.C. Wednesday,June 10:What our judges do when gangsters get to court. Thursday,June 11: How can we stop our children from becoming involved in gangs? Expert panel:Live streaming of Justice Education Society video at vancouversun.com,June 11,7 p.m. tackle different levels of organized crime and gangs. To effectively go after the highest ranks, police need legislative changes making it easier to seize the proceeds of crime, Cantera said. “What we need are laws that make asset seizure and forfeiture of assets more easily attainable for police. That’s what we need to protect the public. That is at the root of the problem,” Cantera said. “What makes the upper echelon more vulnerable is when they attain their assets. That’s when they become vulnerable to law enforcement and it has been difficult for us to be able to get to it.” STORY CONTINUES ON A11