Thirteen Colonies

advertisement

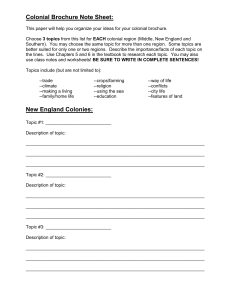

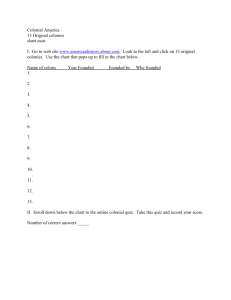

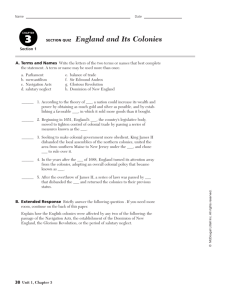

Thirteen Colonies NEW ENGLAND COLONIES Colonies - Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island Climate/Geography - Colonists in the New England colonies endured bitterly cold winters and mild summers. Land was flat close to the coastline but became hilly and mountainous farther inland. Soil was generally rocky, making farming difficult. Cold winters reduced the spread of disease. Religion - The New England colonies were dominated by the Puritans, reformers seeking to "purify" Christianity, who came over from England to practice religion without persecution. Puritans followed strict rules and were intolerant of other religions, eventually absorbing the separatist Pilgrims in Massachusetts by 1629. Life in New England was dominated by church, and there were severe consequences for those who failed to attend, or, those who spoke out against the Puritan ways. Singing and celebrating holidays were among things prohibited in Puritan New England. Economy - New England's economy was largely dependent on the ocean. Fishing (especially codfish) was most important to the New England economy, though whaling, trapping, shipbuilding, and logging were important also. Eventually, many New England shippers grew wealthy buying slaves from West Africa in return for rum, and selling the slaves to the West Indies in return for molasses. This process was called the "triangular trade." MIDDLE COLONIES Colonies - New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware Climate/Geography - The Middle colonies spanned the Mid-Atlantic region of America and were temperate in climate with warm summers and cold winters. Geography ranged from coastal plains along the coastline, piedmont (rolling hills) in the middle, and mountains farther inland. This area had good coastal harbors for shipping. Climate and land were ideal for agriculture. These colonies were known as the "breadbasket" because the of the large amounts of barley, wheat, oats, and rye that were grown here. Religion - Religion in the Middle Colonies was varied as no single religion seemed to dominate the entire region. Religious tolerance attracted immigrants from a wide-range of foreign countries who practiced many different religions. Quakers, Catholics, Jews, Lutherans and Presbyterians were among those religious groups that had significant numbers in the middle colonies. Economy - The Middle Colonies enjoyed a successful and diverse economy. Largely agricultural, farms in this region grew numerous kinds of crops, most notably grains and oats. Logging, shipbuilding, textiles production, and papermaking were also important in the Middle Colonies. Big cities such as Philadelphia and New York were major shipping hubs, and craftsmen such as blacksmiths, silversmiths, cobblers, wheelwrights, wigmakers, milliners, and others contributed to the economies of such cities. SOUTHERN COLONIES Colonies - Maryland, Virginia, North and south Carolina, Georgia Climate/Geography - The Southern Colonies enjoyed warm climate with hot summers and mild winters. Geography ranged from coastal plains in the east to piedmont farther inland. The westernmost regions were mountainous. The soil was perfect for farming and the growing season was longer than in any other region. Hot summers, however, propagated diseases such as malaria and yellow fever. Religion - Most people in the Southern Colonies were Anglican (Baptist or Presbyterian), though most of the original settlers from the Maryland colony were Catholic, as Lord Baltimore founded it as a refuge for English Catholics. Religion did not have the same impact on communities as in the New England colonies or the Mid-Atlantic colonies because people lived on plantations that were often distant and spread out from one another. Economy - The Southern economy was almost entirely based on farming. Rice, indigo, tobacco, sugarcane, and cotton were cash crops. Crops were grown on large plantations where slaves and indentured servants worked the land. In fact, Charleston, South Carolina became one of the centers of the American slave trade in the 1700's. Read the passage and answer the questions. The holiday of Thanksgiving was born from the Puritan settlement of Plymouth, on the coast of present-day Massachusetts. Puritan separatists, desperate for religious freedom, left England in 1607 for the Netherlands under increasing pressure from the crown to conform. Although they were allowed religious freedom, they were not granted citizenship in the Netherlands, and hence, could not secure meaningful jobs and were restricted to those that were low-paying and unskilled. Some Puritans, disheartened by the drifting of their children from the church, made arrangements with the Merchant Adventurers (a London joint-stock company) to relocate to America. Payment for their passage was made in exchange for future repayment and a percentage of future profits made by the settlement. 35 Pilgrims (as they would come to be known) boarded the Mayflower with 67 other passengers and set sail for Virginia on September 16, 1620. The treacherous voyage across the stormy Atlantic Ocean lasted 10 weeks. When the Mayflower finally approached America, it was no where near Jamestown or even Virginia. On November 11, 1620, the Mayflower reached land off present-day Cape Cod. Some historians believe the Mayflower never intended to sail to Virginia, but rather had secretly planned to sail to New England. Many of the passengers threatened mutiny because they were supposed to be brought to Virginia. As a result, the Mayflower Compact was drafted which guaranteed the equal treatment of all settlers in the new colony. The Mayflower Compact further documented the colony's continued allegiance to England, but also called for the establishment of an independent, civil government. The Compact was signed by 41 male passengers and the decision to remain at Plymouth, rather than to spend more time at sea was made. The settlers organized themselves into a group known as the Council of New England. The council promised one hundred acres of land to those settlers who remained at Plymouth for seven years. The Mayflower and its passengers explored the coast of Massachusetts for several weeks before finding the perfect spot at Plymouth on December 21, 1620. Life in Massachusetts was difficult for the settlers. Half of the original passengers on the Mayflower died of disease , starvation, and the harsh Massachusetts winter. Unlike Jamestown, however, Indian attacks were not a constant threat. Rather, the local Wampanoag Indians were responsible for the colonists survival. Squanto, who was kidnapped and had experienced life in Europe as a slave and later as an observer of European culture in a monastery, had recently returned to Massachusetts only to find his former village ravaged by death and disease. He assimilated into the Wampanoag village located at Plymouth and later joined the Pilgrim colony at Plymouth when they learned he could speak English. Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to establish friendly relations with the Indians and how to plant crops, fish, and trap mammals for the fur trade. If it wasn't for Squanto, the Wampanoags and their sachem Massasoit, all of the settlers would have surely perished. One year after the landing of the Mayflower, the surviving Pilgrims celebrated their first fall harvest with a prodigious feast. They invited 91 of their Indian friends. The feast was the first ever Thanksgiving. 1. What phrase best describes the Puritans of Plymouth. A. Dependent on their Indian neighbors. B. They were able to survive because of their resourcefulness. C. Interested in gold and riches. D. They probably wanted to go back to England. 2. What hoilday was born from the settlement of Plymouth? _________________________________________________________ 3. Why did some passengers threaten to mutiny? A.The trip took too long. B. They were criminals. CThey thought they were going to Virginia but were actually going to Mass. D. They thought they were going to Mass. but were actually going to Virginia. 4. About how many passengers died of disease, winter and starvation? a. 35 b. 67 c. 102 d. 51 5. What did the Mayflower Compact not do? a. Proclaim allegiance to England. b. Guarantee that all settlers would be treated as equals. c. Called for the establishment of an independent government. d. Proclaim independence from England. 6. Why did the Puritans leave England? a. They wanted more money b. They wanted religious freedom c. They wanted new scenery d. They were kicked out 7. What does "conform" mean? a. To be the same as b. To be different from c. To give money Interactive Scavenger Hunt: 1. Log onto the website below and click on the link: Interactive Scaveger Hunt. http://www.mrnussbaum.com/wordsearch/13search.htm 2. Complete worksheet Apothecary Colonial apothecaries were what we think of as doctors. They treated patients, made and prescribed medicines, made house calls, and taught apprentices. Some even performed surgeries - and remember most surgeries occurred at the time without anesthesia. Even in the 1600s and 1700s, apothecaries were sophisticated in their knowledge of remedies. For example, they knew that calamine could be used to treat itchy skin problems and that heartburn could be cured with chalk (similar to modern-day Tums). Apothecaries often used leeches to "bleed" people and chinchona bark to treat fevers. Some Apothecaries crafted their own remedies from any number of substances, herbs, animal parts, and other mixtures. Wigmaker In affluent villages and cities, full of wealthy landowners and plantations, the wigmaker was very important. Wigmakers made perukes (wigs) and fashioned the hair of the elite. Wigs were made of horse, goat, or yak hair and skillful wigmakers could customize a wig to the preferences of the customer or to the styles popular in London. The wigmaker was especially busy when the courts were in session as the judges and attorneys each required their own specialized hair pieces. Harness/Saddle Maker Because few colonists could had much money, let alone owned a carriage, harness makers catered to the rich. A custom-made harness could cost a month's wages, take thirty hours to fashion, and would last 25-30 years. Harness makers also made and repaired other leather goods such as couch cushions, pistol buckets, razor cases, cartridge cases, bags and pouches, water buckets, and horse riding accessories. Becoming a harness or saddle maker was hard work. Apprenticeships usually started around age 13, and apprentices had to learn the complexities of fashioning systems of cutting, stitching, and assembly that connected a horse to a carriage. They also had to learn to make the special thread used in leatherwork that was made of flax or hemp and coated in beeswax. Harness and saddlemakers learned to use specialized knives, awls, and dividers that cut leather. Such craftsman also knew how to make different saddles such as sidesaddles for ladies, racing saddles, saddles for luggage (called portmanteaus) and saddles for carriage drivers (called postilions) and how to make saddles of different colors, textures, and waterproofing strength. Blacksmith The Blacksmith was an essential merchant and craftsman in a colonial town. He made indispensable items such as horseshoes, pots, pans, and nails. Blacksmiths (sometimes called ferriers) made numerous goods for farmers including axes, plowshares, cowbells, and hoes. They also made hammers, candleholders, tools, files, locks, fireplace racks, and anvils. Most of the blacksmith's work was done in his personal forge in which scalding bars of iron were hammered with heavy sledges to fashion the iron into various shapes. The road to becoming a successful blacksmith was long and hard. Apprenticeships started at age 14 or 15 and could last up to seven years. At first, an apprentice would simply observe his master before helping with easy tasks. Eventually, the apprentice would learn more complicated tasks like heating and bending iron. Finally, the apprentice would be tasked with fashioning some kind of metal "master piece" that would be judged by his master. If the piece was adequate, the apprentice would pass his apprenticeship and became a journeyman - a traveling blacksmith who would repair metal goods in nearby villages. If all went well, the journeyman would have earned enough money through his work to open his own shop. Milliner A milliner's business was much like a modern-day clothing store. Here, men and women could shop for the day's fashionable clothes and accessories. Interestingly enough, a millinery was just about the only business in colonial times that could be owned and managed by a woman. A milliner sold a variety of things such as fabric, hats, ribbons, hair pieces, dolls, jewelry, lottery tickets, games, and medicines. Most of the items for sale were imported from England. In addition, milliners hired people called mantua makers, who would craft customized outfits, costumes, dresses, and jackets for women, and tailors who would perform similar duties for men. Hatter In colonial times, nearly everyone wore some kind of head covering, making the hat industry very important. A man’s hat advertised his social status. Hats that were more elaborate represented greater wealth or status. Colonial hats were made of beaver skin, wool, cotton, or straw. Colonial hatters knew how to make many different kinds of hats such as a knitted caps, broad-brimmed hats (which was the most popular), or upturned brim-tricorne hats (three-cornered hats). Because beaver furs were so numerous in the New World, the hat industry was one of the first that actually took business away from Great Britain. Danbury, Connecticut would become the epicenter of hat production in the colonies. At one point, the city produced five million hats in one year. Interestingly, part of the process of making hats involved “carroting” or washing the furs with a type of steaming hot, orange liquid. The liquid was full of mercury, which would attack the central nervous systems of the workers when it became airborne. Such workers would experience blurring of vision, loss of balance, delusions, and uncontrolled twitching of the muscles. Known as the Danbury Shakes, this phenomenon would give rise to the statement “mad as a hatter.” Cooper Coopers were tradesman who made casks, buckets, barrels, and containers for flour, gunpowder, tobacco, shipping, wine, milk, and other liquids. One kind of container, the hogshead, was used to ship huge quantities of tobacco from the colonies to England. Because the demand for containers was high, colonial coopers made millions of such containers every year. Although coopers are traditionally known for creating barrels (casks), it was actually the “tight cooper” who made them. Other coopers began specializing in making specific types of containers that they could mass produce quickly. The construction of a barrel (more accurately called a cask) took skill, experience, and significant manual labor. It was very difficult to construct the perfect cask, with a bulging round center and with sides that taper inward toward both ends. Clear white oak staves (wooden planks for barrels) were split from the centers of mature trees. The tight cooper would then fashion the wooden parts with axes and knives before gathering them in a circular formation and securing them with iron rings. The staves were then heated to make them pliant (flexible) and pulled together with a special tool called a windlass. They were then banded with hickory hoops. Grooves were cut into lips that were formed to make sure the barrelheads fit tightly. Next, the lid was made. Finally, the cooper would cut a hole in the top and side and then fit the holes with plugs. This was done so people could see what was in the barrel. The word cooper comes from the Middle English word “couper,” which means tub or container. Brickmaker Brickmakers were important in colonial towns and their trade contributed to the overall appearance of the village or city. Brickmakers made their products by digging clay from the ground. They would then mix the clay with water and mash it with their feet to produce the right consistency in an area called a treading pit. Debris such as sticks, rocks, and leaves would then be removed. Different colored bricks were made by adding sand or ashes to the mixture. The mixture would then be placed in a wooden mold to make the right shape. Within the molds, the brick mixtures would dry for a week or so before being moved to a drying shed where they would be stored for up to six weeks. When they were fully dried, they would be fired in a brick kiln sealed with clay for up to six days at temperatures approaching 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit where they would glow yellow from the intense heat. Up to 20,000 bricks could be fired at a time, though not all would be usable. Printer Colonial printers printed books, newspapers, pamphlets and other publications. Their shops sometimes served as mail centers as well. Printers who printed newspapers bought their paper from a paper mill and made the ink in their shops. Paper was made from linen and cloth and ink was made from tannin, iron sulfate, gum, and water. Printing a publication such a newspaper was a comprehensive and complicated task. First, the type was set. A type was a single piece of metal with a letter, number, or point of punctuation. Setting the time was a taxing, cumbersome task. A single page of a colonial newspaper could take up to 25 hours of labor to produce. The type setting process was done by an employee or apprentice of the printer known as the compositor. An inking pad or “beater” was used to spread the ink over the type. The type would be arranged and held with an apparatus called a composing stick. The stone was a large flat surface that held the work to be printed, and the press was the machine that transferred the arranged lettering to a page. The press itself functioned by squeezing the paper against the arranged type with about 200 pounds of pressure to ensure the ink was deposited boldly and evenly on the paper. The paper was then set aside to dry before the other side was printed. Among the most famous of colonial printers was Benjamin Franklin, who published newspapers and books from his printing press in Philadelphia. One of Franklin’s most famous publications was called Poor Richard’s Almanac, a book of predictions, information, and advice, in which popular sayings were first published such as “a penny saved is a penny earned” and “three may keep a secret if two of them are dea Cobbler Shoemaking was one of the earliest industries in the original 13 colonies. Shoemakers may have been with John Smith on one of the maiden voyages to the New World that resulted in the establishment of the Jamestown colony. At the latest, shoemakers arrived in the New World in 1610. Shoemakers made shoes first by making wooden “lasts,” or blocks of foot-shaped wood carved into different sizes. Next, a leather “upper” was stretched over the last and fastened with glue until it was ready to be fastened to the sole. The sole would be pounded with metal tools and an awl was used to cut holes. Then the upper was removed from the last and the sole and upper were sewn together before the shoe was cleaned, polished, and fitted with a heel. Finally, the shoes were hung in the shoemaker’s store. A standard pair of shoes would take between eight and ten hours to make. Early shoemakers used the same pattern to make a pair of shoes, meaning the left and right shoes were exactly the same. Interestingly, the making of boots and shoes for men was a completely different trend than making ladies shoes. Bootmaking was the most prestigious pursuit in the shoe industry and competition was often fierce among rival bootmakers. To make matters worse, local factories began mass producing shoes and many wealthy citizens would have their shoes imported from England. Tavern Keeper Early American taverns were important gathering places for townspeople and for travelers. Because of the arduous conditions in early colonial travel, taverns were generally erected every few miles on main roads to accommodate weary and hungry travelers. Although people could certainly buy and drink beer, ale, wine, and other liquors, as well as enjoy a good meal and get a good night’s sleep, taverns were places where townspeople socialized, exchanged ideas, talked about local politics, and even made laws and declared action. For example, the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg, Virginia, served as the staging grounds for Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and other Virginians to form Committees of Correspondence with other colonial leaders to protest and monitor actions of the British Crown against them. Wheelwright The wheelwright was important tradesman in colonial towns. They made wheels for wagons, carriages, and riding chairs. Because colonial roads were rocky and rugged, wheels had to be made to handle the rough conditions. Wheelwrights also built or repaired carts, wheelbarrows and wagons. Wheelwrights had to have precise measuring skills as well as knowledge of basic geometry. Wheelwrights were very important in farming regions, where farmers needed wheeled vehicles to Constructing such a wheel was considerably difficult and took the skills of metal working and carpentry. Wheelwrights cut, chiseled, fashioned, and shaped wheels from wood. The spokes and hubs were also made of wood. They used iron rims, often made by local blacksmiths, to fit around the exterior of the wheels. Of particular difficulty was the process of perfecting the mortise and tenon process, where the wheelwright carves a cavity (mortise) in a piece of wood and shapes the tenon to fit in the cavity snugly. This is how the spokes are fastened in the hub and rim. Candlemaker (Chandler) Being that electric lights did not exist at the time, candlemaking in colonial times was an important trade. Although women made candles in smaller towns and villages, a tradesman called a chandler made candles in larger towns. To make a candle, a chandler would first craft the wick with thin pieces of cotton or linen. Next, he would heat up tallow or animal fat before dipping the wick into it. The wick would be dipped into the burning animal fat several times. This “dipping” was done until the candle was the desired size. Once the candle had hardened, the wick was trimmed and the candle was ready to be used. Such candles, made from tallow, gave off unpleasant odors. Chandlers also made candles from whale oil. These kind of candles didn’t smell any better than tallow candles but were more durable Wealthy people could buy candles made of beeswax, but these were expensive and not available to everyone. Some chandlers attempted to make candles using berries from the bayberry shrub, but this process of very time consuming and not cost-effective. Gunsmith Being a gunsmith in colonial America required several specialized skills in working with metal and wood. Apprenticeships for learning the trade could take up to seven years. Colonial gunsmiths mainly repaired guns, axes, and other metal tools because most firearms were imported from England because they were cheaper. In England, gunsmiths specialized in making one or two parts such as the barrel (the long tube through which the bullet passes), stock (the wooden part of the gun that serves as the grip and holds the firing mechanisms), or firelock (the firing mechanism). This kept production high and costs low and also marked the infancy stage of what came to be known as the assembly line system of production. In colonial America and England, most of the guns in existence were flintlocks. A flintlock was a piece of flint set in a moveable cock. When the trigger was pulled, the cock fell causing the flint to strike a piece of steel, creating sparks. The sparks would come in contact with the gunpowder which would ignite the main charge in the barrel. Guns were more important in colonial America than they are today in America. Colonists needed guns to hunt for their food, and if necessary, protect themselves from Native Americans (in frontier lands). American gunsmiths, however, did produce the long rifle, a hunting rifle used in America’s frontier lands, particularly Pennsylvania and Kentucky. The long rifle allowed hunters to kill deer from long distances. General Store Keeper The General Store was an important part of any colonial town or community. It often served as a gathering point where people could debate politics, or sift through the latest European imports. Coffee, produce, cheeses, and candles were among the many products sold at the general store. Merchants at general stores also sold metal goods, tins, wrought-iron decorations, playing cards, barrels, furs, guns, clothing, and anything else imaginable that could be sold. Farmers would often come with their extra meat, vegetables, and eggs to sell or trade. Silversmith Silversmiths were among the most numerous of colonial craftsman. Business could often be difficult as many wealthy citizens imported their silver objects from England. Some silversmiths in America were forced to make their livings by importing silverware from England and selling it. Furthermore, it was very difficult to obtain unfinished silver and colonial silversmiths often had to buy the old silver pieces from citizens just to have silver to work with. Many silversmiths (who also called themselves goldsmiths) made relatively few original items such as spoons, buttons, and shoe buckles. They would also repair items. Silversmiths fashioned their objects from thick pieces of metal called ingots. Upon an anvil, the ingot would be hammered until it was thin enough. It was then placed over a stake where it was shaped and smoothed. The last step was polishing the piece with pumice, decomposed limestone (known as tripoli) and powdered red iron ore (known as jeweler’s rouge).