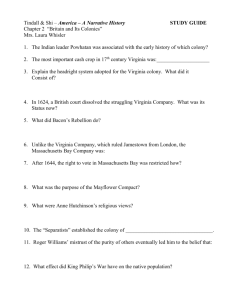

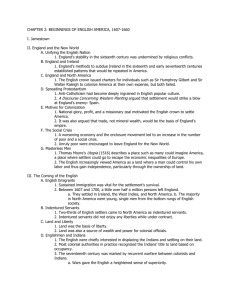

Give Me Liberty 3rd Edition

advertisement