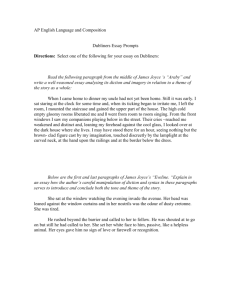

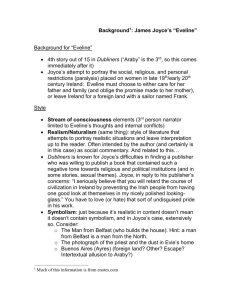

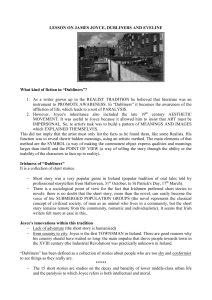

Dubliners integrale TB - Aheadbooks, Black Cat

advertisement