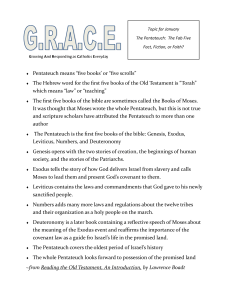

Studies in the Pentateuch: The Books of Moses

advertisement