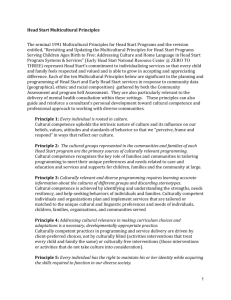

NASW Cultural Competence Standards for Social Work

advertisement