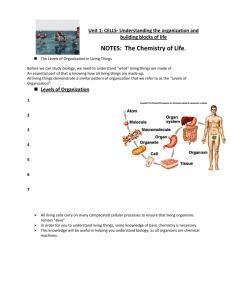

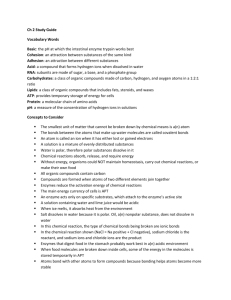

2 | the chemical foundation of life

advertisement