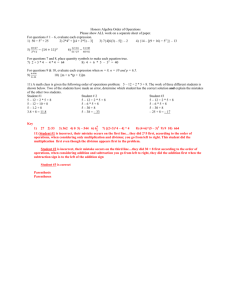

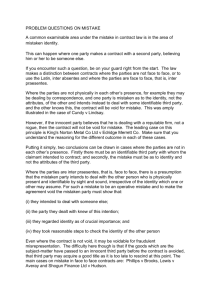

to err is human - UNLV - William S. Boyd School of Law

advertisement