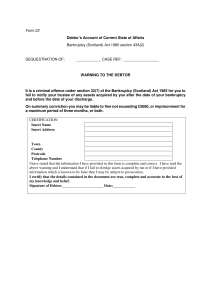

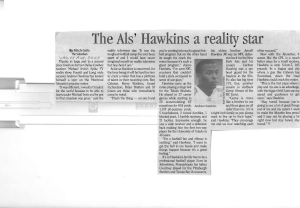

William M. Hawkins, III aka Trip Hawkins, Debtor, Will

advertisement