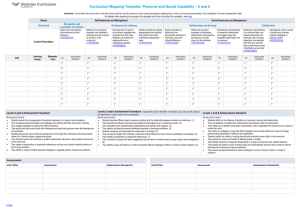

The importance of play in children's lives

advertisement