- Schizophrenia Research

Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210 www.elsevier.com/locate/schres

A comparison of symptoms and family history in schizophrenia with and without prior cannabis use: Implications for the concept of cannabis psychosis

J. Boydell

⁎

, K. Dean, R. Dutta, E. Giouroukou, P. Fearon, R. Murray

Division of Psychological Medicine, PO Box 63, Institute of Psychiatry, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, SE5 8AF, United Kingdom

Received 5 October 2006; received in revised form 11 March 2007; accepted 17 March 2007

Available online 25 April 2007

Abstract

Background: There is considerable interest in cannabis use in psychosis. It has been suggested that the chronic psychosis associated with cannabis use, is symptomatically distinct from idiopathic schizophrenia. Several studies have reported differences in psychopathology and family history in people with schizophrenia according to whether or not they were cannabis users. We set out to test the hypotheses arising from these studies that cannabis use is associated with more bizarre behaviour, more thought disorder, fewer negative symptoms including blunted affect, more delusions of reference, more paranoid delusions and a stronger family history of schizophrenia.

Method: We used a case register that contained 757 cases of first onset schizophrenia, 182 (24%) of whom had used cannabis in the year prior to first presentation, 552 (73%) had not and 3% had missing data. We completed the OPCRIT checklist on all patients and investigated differences in the proportion of people with distractibility, bizarre behaviour, positive formal thought disorder, delusions of reference, well organised delusions, any first rank symptom, persecutory delusions, abusive/accusatory hallucinations, blunted affect, negative thought disorder, any negative symptoms (catatonia, blunted affect, negative thought disorder, or deterioration), lack of insight, suicidal ideation and a positive family history of schizophrenia, using chi square tests. Logistic regression modelling was then used to determine whether prior cannabis use affected the presence of the characteristics after controlling for age, sex and ethnicity.

Results: There was no statistically significant effect of cannabis use on the presence of any of the above. There remained however a non-significant trend towards more insight (OR 0.65

p = 0.055 for

“ loss of insight

”

) and a finding of fewer abusive or accusatory hallucinations (OR 0.65

p = 0.049) of borderline significance amongst the cannabis users. These were in the hypothesised direction.

There was no evidence of fewer negative symptoms or greater family history amongst cannabis users.

Conclusion: We found few appreciable differences in symptomatology between schizophrenic patients who were or were not cannabis users. There were no differences in the proportion of people with a positive family history of schizophrenia between cannabis users and non-users. This argues against a distinct schizophrenia-like psychosis caused by cannabis.

© 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Schizophrenia; Cannabis; Symptom-profile; Family history

⁎

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 207 8484015.

E-mail address: j.boydell@iop.kcl.ac.uk

(J. Boydell).

0920-9964/$ - see front matter © 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.014

204

1. Introduction

There is considerable interest in cannabis use in psychosis. There is evidence from several studies that heavy cannabis use might initiate an episode of schizo-

Johns et al., 2004; Andreasson et al., 1987; Zammit et al.,

).

We have previously shown that as the prevalence of cannabis use in South London, UK, has risen, the incidence of schizophrenia (and this would include schizophrenia-

like psychoses) has also risen ( Boydell et al., 2006

).

It has been suggested that the chronic psychosis associated with cannabis use, is symptomatically distinct from idiopathic schizophrenia. A number of studies have compared the symptom profiles of schizophrenia with and without cannabis use, with mixed results (

Thornicroft et al., 1992; Bersani et al., 2002a,b; Buhler et al., 2002,

), reviewed by

2004 . The largest study with 125 male participants who

were admitted with chronic schizophrenia, found less positive thought disorder and fewer negative symptoms

(including affective flattening, apathy, asociality, alogia, impaired attention as measured by SANS) amongst the

cannabis consumers (54 in total) ( Bersani et al., 2002b

). A large study of substance misuse (which included alcohol, cannabis, hypnotics, hallucinogens, opiates and stimulants) compared psychopathology in 447 inpatients with mostly chronic ICD9 schizophrenia, who were classified as having a lifetime diagnosis of substance use disorder or not. The cannabis misusers (approx 65, 1/3 of the substance use group were cannabis users) were not treated as a separate group. Overall there were few differences between the substance misuse group and the others but amongst the current users (of any substance) there were trends (non-significant at the p = 0.01 level) towards more incoherence, more delusions of reference, fewer delusions of guilt, more visual hallucinations, more First Rank symptoms and less insight (

).

It has also been suggested that people who develop schizophrenia after cannabis use are more likely to have a positive family history of schizophrenia suggesting an interaction between cannabis use and genetic liability.

found that 23 people with schizophrenia who had positive urine tests for cannabis, were significantly more likely (approx. 10×) to have a family history of schizophrenia than 46 people with schizophrenia who had negative urine tests.

We wanted, therefore, to determine whether the prevalence and type of symptoms differed between

J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210 cannabis users and non-users in a large sample of people with first onset schizophrenia. We hypothesised that those who had used cannabis would demonstrate more bizarre behaviour, more thought disorder, fewer negative symptoms including blunted affect, more delusions of reference and more paranoid delusions. We also wanted to test the hypothesis that people with schizophrenia who had used cannabis prior to developing psychosis were more likely to have a positive family history, in a first or second degree relative, of the disorder.

2. Method

This study was carried out using cases of schizophrenia from the Camberwell Case Register which has been

compiled over the past four decades ( Wing and Hailey,

1972; Castle et al., 1991; Allardyce et al., 2000, 2001;

Boydell et al., 2001, 2003, 2006 ).

2.1. Sample

The database contains clinical and demographic data on people aged over 16 years, from South East London, who presented (admissions and non-admissions) to psychiatric services with any possible psychotic illness between 1965 and 2004. The case finding methodology is more fully described in previous publications (

recent years, from a slightly reduced geographical area. All patients' records were checked to ensure they were true incident i.e. first episode cases (i.e. had not presented with, or had prior psychiatric treatment for, psychosis), and then were rated using the OPCRIT checklist (see

1991, 1998; Allardyce et al., 2001; Boydell et al., 2001,

for further details including evidence of interrater reliability). The OPCRIT checklists were then used to generate diagnoses according to the Research Diagnostic

Criteria, RDC ( McGuffin et al., 1991

). We used Research

Diagnostic Criteria, RDC ( Spitzer et al., 1978 ) as these

criteria have been incorporated in the OPCRIT system from the beginning, thus avoiding difficulties with the changes between different versions of DSM and ICD.

Within the RDC criteria we chose the narrow definition

(i.e. more than 2 weeks duration) of schizophrenia (see

Appendix A for description,

) as this enabled us to avoid including brief psychotic reactions to intoxication. Cannabis use prior to presentation was rated from the case notes as either used, not used, or not known.

This was based on self report and urine drug screening so that if either was positive for cannabis the item was rated as

“ used

”

. Family history was also rated from the case-notes

J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210 as present or absent and was defined as “ a definite history of schizophrenia in a first or second degree relative ” .

2.2. Measurement of symptoms

The presence or absence of symptoms was measured by the OPCRIT checklist using the strict OPCRIT definitions. The checklist was rated using all the information in the case notes for the first year after presentation, by psychiatrists with academic training and clinical experience. Training in using Opcrit was also undertaken and interrater reliability was regularly monitored.

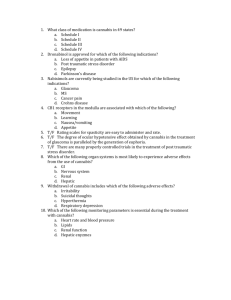

Based on the findings of the previous studies, knowledge of the major groups of symptoms of schizophrenia and a desire to avoid excessive numbers of comparisons, we chose to test differences between the proportion of people with distractibility, bizarre behaviour, positive formal thought disorder, delusions of reference, well organised delusions, any first rank symptom, persecutory delusions, abusive/accusatory hallucinations, blunted affect, negative thought disorder, any negative symptoms (any one of catatonia, blunted affect, negative thought disorder, deterioration), lack of insight, suicidal ideation and a positive family history of schizophrenia.

The OPCRIT definitions of these symptoms are given in

Appendix B. All were rated as present or absent for the first year after first presentation.

2.3. Statistical analyses

We began with a univariate analysis to compare the proportions of cannabis users and non-users with each of the above symptoms and characteristics using chi squared tests. We then used logistic regression with the symptom/ characteristic as the outcome and cannabis use as the main explanatory variable to adjust for age and sex and ethnicity for each symptom that was associated with cannabis use in the univariate analysis.

205

2.4. Power

It is possible that some of the cannabis use could have been coincidental or secondary to the schizophrenia, or possibly an attempt at self medication; this would therefore dilute any differences in symptomatology should a specific

“ cannabis psychosis

” exist. We therefore carried out power calculations to estimate power for relatively small differences.

The main hypothesis was that cannabis users had fewer negative symptoms. The study had 92% power at the 5% significance level to find a drop of 10% in the presence of negative symptoms amongst the 173 cannabis users, from 20% amongst the 514 non-users.

8% of the non-cannabis users had blunted affect at presentation. This analysis had 98% power to find a drop to 1% in the cannabis users and 70% power to find a drop to 3%.

With respect to the hypothesis that a higher proportion of cannabis users have a positive family history of schizophrenia, the study had 97% power to replicate the 10 fold difference found by

between 0.7% and 7% at the 5% significance level. It had 89% power to find an increase from the 12% in the non-users in the study to 22% in the users at the 5% significance level.

3. Results

A total of 757 cases met the RDC for narrow schizophrenia; 182 (24%) had used cannabis prior to first presentation, 552 (73%) had not and 23 (3%) could not be classified as having used cannabis or not. The sociodemographic characteristics and family history of the cannabis users and non-users are shown in

There were significant gender differences between the cannabis users and non-users (fewer women used cannabis) and the cannabis users were younger. There was no association between ethnicity and cannabis use.

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics and family history of the cannabis users compared to the non-cannabis users

Cannabis users No use of cannabis

Age

Sex

Family history of schizophrenia

Values in bold are significant at 0.05 level.

b

40

N

40

Male

Female

Positive

Negative

No + %

164 (90%)

18 (10%)

147 (36%)

35 (10%)

25 (15%)

140 (85%)

No + %

373 (68%)

175 (32%)

258 (64%)

294 (90%)

57 (12%)

428 (88%)

Chi square

34.13

64.15

1.29

p value p b

0.0001

p b

0.0001

p = 0.256

206 J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210

Table 2

Univariate analysis: psychopathology according to cannabis user status

Cannabis users (no. and %)

Distractibility

Bizarre behaviour

Positive thought disorder

Catatonia

Negative thought disorder

Blunted affect

Deterioration premorbid function

Delusions of reference

Well organised delusions

Persecutory delusions

Abusive hallucinations

Lack of insight

Any negative symptom

Any first rank symptom

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Deteriorated

Not

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

Loss of insight

Has insight

Present

Absent

Present

Absent

88 (51%)

40 (23%)

133 (77%)

143 (83%)

30 (17%)

68 (39%)

105 (61%)

128 (74%)

44 (26%)

44 (25%)

129 (75%)

91 (53%)

81 (47%)

41 (24%)

132 (76%)

80 (46%)

93 (54%)

55 (32%)

118 (68%)

10 (6%)

163 (94%)

33 (19%)

140 (81%)

40 (23%)

133 (77%)

115 (68%)

55 (32%)

84 (49%) a b c d e

Cannabis users were more distractible.

Cannabis users had more negative thought disorder.

Cannabis users had fewer well organised delusions.

Cannabis users had fewer abusive/accusatory hallucinations.

Cannabis users had more insight.

No cannabis use (no. and %)

250 (49%)

183 (36%)

330 (64%)

438 (85%)

77 (15%)

258 (51%)

250 (49%)

429 (84%)

82 (16%)

98 (19%)

416 (81%)

293 (57%)

218 (43%)

70 (14%)

446 (86%)

236 (46%)

280 (54%)

127 (25%)

388 (75%)

28 (5%)

488 (95%)

58 (11%)

458 (89%)

43 (8%)

471 (92%)

359 (70%)

152 (30%)

262 (51%)

0.41

0.28

9.29

0.56

6.8

7.77

3.2

1.03

Chi square

9.8

0.013

3.385

0.031

6.93

0.013

P value

0.002

a

0.91

0.07

0.86

0.008

b

0.91

0.52

0.59

0.002

c

0.45

0.009

d

0.005

e

0.07

0.31

There were no significant differences in the proportion of people with a positive family history, between cannabis users and non-users. The results of the univariate analysis are shown in

. This showed that cannabis users were more distractible, had more negative thought disorder, fewer well organised delusions and fewer abusive auditory hallucinations. Cannabis users had better insight.

There were no statistically significant (at the p = 0.05 level) differences, by cannabis use, in the proportion of people with bizarre behaviour, positive formal thought disorder, catatonia, blunted affect, deterioration from premorbid functioning, persecutory delusions, any negative symptom or any First rank symptom. Logistic regression modelling was used to adjust for any possible confounding by age, gender or ethnicity and to give odds ratios to estimate the effect of cannabis use on the presence of the symptoms that were shown to vary in the univariate analysis. The results are shown in

. After adjusting, there was no statistically significant effect of cannabis use on the presence of negative thought disorder, well organised delusions and distractibility. There remained however a non-significant trend towards more insight (OR 0.65

p = 0.055 for

“ loss of

Table 3

Multivariate analysis:odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regression for characteristic symptoms with cannabis use as the main explanatory variable adjusted for age sex and ethnicity

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval

P value

Distractibility 1.42 (0.91

–

2.23) p = 0.125

Negative thought disorder 1.33 (0.82

–

2.17) p = 0.29

Well organised delusions 0.72 (0.47

–

1.09) p = 0.118

Abusive/accusatory voices 0.69 (0.48

–

0.999)

Lack of insight p = 0.049

0.65 (0.42

–

1.009) p = 0.055

J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210 insight ” ) amongst the cannabis users and a finding of fewer abusive or accusatory hallucinations (OR 0.65

p = 0.049) of borderline significance at the p b

0.05 level. Both of these were in the hypothesised direction.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of findings

We found few differences in symptomatology, in the first year after presentation with schizophrenia, between cannabis users and non-users in South East London. We did not confirm previous reports of fewer negative symptoms and in particular there was no difference in the proportion of people with blunted affect. We found a non-significant trend towards better insight amongst the cannabis users and this might possibly be because the cannabis users might have had less neurodevelopmental and cognitive predisposition. The finding of a trend, of borderline significance, of fewer abusive or accusatory hallucinations might reflect differing prior life experience between the two groups, but this is speculative. We did not find any evidence that cannabis users with schizophrenia were more likely to have a family member with the disorder.

4.2. Methodological issues

A major strength of this study is the large number of cases; it is to our knowledge the largest study to compare cannabis using and non-using schizophrenic patients and is therefore less susceptible to random error. The study had sufficient power to control for the potential confounders of age, sex and ethnicity. Another major strength is that the cases were all first onset therefore avoiding confounding by treatment compliance and chronicity. The symptoms were rated to compile the case register without any a priori hypotheses reducing the possibility of observer bias.

Similarly there is no reason to suspect selection bias based on cannabis use especially as inpatients and outpatients were included. It is unlikely that bias occurred earlier when the case histories were taken and the case records written as interest in cannabis as an aetiological agent has only arisen in the last few years and hypotheses regarding different symptom profiles were not well known.

The main limitations of the study are that we were reliant on the accuracy of the history of cannabis use given by the patients (or the recording of urine drug screens), and further that we were only able to classify cannabis use as present or absent as data regarding intensity of use was not recorded in a consistent or standardised way. Therefore we could not test dosage or threshold effects. However where

207 level of use was documented it was generally more than once a week. Similarly we do not have reliable information about ongoing use. All the cannabis use was before first presentation but it is possible that occasionally the cannabis use began after the onset of prodromal symptoms however this self medication hypothesis has been largely refuted by

other studies ( Henquet et al., 2005a,b ). Another limitation

is that the symptoms were rated from case records although these followed a set format (that OPCRIT was designed around) and the psychiatrists who wrote them were all trained in the same way. Finally there was no independent verification of the presence or absence of family history of schizophrenia. This was also rated from case notes and therefore it is possible that cases might have been missed but this is unlikely to have led to differential misclassification between the two groups as the case register was not set up to answer any particular question. It would have been very interesting to include family history percentages from age, sex and ethnicity matched population controls but we do not have these controls. We were also not able to establish morbid risks for the two groups of relatives.

Although this was a large study it still may have missed very small differences in symptoms and we have therefore given sufficient detail for a meta-analysis to be carried out if other studies are reported. Although we included the major symptoms, it is possible that there might have been differences in the symptoms that were not analysed and differences in other factors that were not considered.

4.3. Comparison of findings with other studies

Our findings of virtually no differences in symptomatology are in line with many of the small studies

(

McGuire et al., 1995 ; Thornicroft, 1992; Hall and

). Our findings differed from those from Italy (

) and a pilot study of 18 first hospitalised African Americans (

that we did not find a lack of negative symptoms in cannabis users; this might have been because our sample were all first onset whereas the Italian sample also contained chronic cases. We cannot make any statement about any differences in symptomatology between cannabis users and non-users, more than a year following first contact. It would be interesting to test whether cannabis use is associated with the subsequent development of negative symptoms. We were not able to find an increase in positive family history in cannabis users and therefore did not replicate the findings of

, despite sufficient power. In a recent population based study, a cohort of healthy people who had not presented with psychosis were screened for psychotic symptoms and followed up for 20 years to determine the predictors and

208 J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210

course of these symptoms ( Rossler et al., in press ). This

study found that cannabis use at baseline was associated with a consistently high level of

“ schizophrenia nuclear symptoms

”

(very similar to first rank symptoms) over time but not schizotypal symptoms. These results are very consistent with ours.

in a population cohort study found that 44.5% of people treated for cannabis induced psychotic symptoms later developed a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and 77.2% developed further psychotic episodes. The schizophrenia spectrum cases were compared to a group of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders without prior cannabis use. The cases with prior cannabis use were found to be younger. This younger age at onset was also found in our study and probably reflects the demographics of substance misuse in the local population. Finally the proportion of cannabis users is lower than in more recent first episode studies because this study has a long time span beginning before cannabis use was so prevalent.

4.4. Cannabis psychosis

The term cannabis psychosis has been used in several different ways. The two main ways are a brief psychosis that occurs immediately following use and is followed by rapid and complete remission and a schizophrenia-like psychosis that is long lasting and does not have to develop immediately after cannabis use. It has been suggested that this psychosis is distinct from idiopathic schizophrenia

). There might be differences in symptoms, onset, pattern of illness, response to treatment and outcome. We cannot address all of these in our study. It is however particularly important to know whether

“ cannabis psychosis

” is symptomatically distinct from idiopathic schizophrenia as this would suggest that the pathological mechanisms underlying those particular symptoms can be induced by the pharmacological effects of cannabis use. The mechanism by which cannabis use leads to the formation of psychotic symptoms and a psychotic disorder has yet to be fully described. In rats however delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (a major component of cannabis) increases presynaptic dopamine efflux and utilisation in the prefrontal cortex (

).

5. Conclusion

We found few appreciable differences in symptomatology and none in family history between patients with schizophrenia who had been cannabis users and those who had not. This argues against a symptomatically distinct schizophrenia-like psychosis associated with cannabis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Stanley Medical Research

Institute, the Gordon Small Trust and the Wellcome Trust for financial support.

Appendix A. OPCRIT checklist items used to establish a diagnosis of research diagnostic criteria

“

Narrow Definition of Schizophrenia

”

(

Illness duration of at least 2 weeks

Affective symptoms must not be prominent

Two of catatonia, ( speech incoherent, formal thought disorder), (well organised delusional system, grandiose delusions, delusions of influence), (bizarre delusions, widespread delusions, delusions of passivity), delusions with hallucinations lasting a week or more, (thought insertion, thought withdrawal, thought broadcast), abusive/ accusatory/persecutory voices, other non-affective auditory hallucinations where 1 or more of the items in brackets scores 1.

Appendix B. OPCRIT definitions of key symptoms

Bizzare behaviour : Behaviour that is strange and incomprehensible to others. Includes behaviour which could be interpreted as response to auditory hallucinations or thought interference.

Catatonia : Patient exhibits persistent mannerisms, stereotypies, posturing, catalepsy, stupor, command or excitement which is not explicable by affective change.

Distractibility : Patient experiences difficulties concentrating on what is going on around because attention is too easily drawn to irrelevant or extraneous factors.

Positive formal thought disorder : The patient has fluent speech but tends to communicate poorly due to neologisms, bizarre use of words, derailments, loosening of associations.

Negative formal thought disorder : Includes paucity of thought, frequent thought blocking, poverty of speech or poverty of content of speech.

Blunted affect : Where the patient's emotional responses are persistently flat and show a complete failure to ‘ resonate ’ to external change.

Suicidal ideation : preoccupation with thoughts of death (not necessarily own) Thinking of suicide, wishing to be dead, attempts to kill self.

Persecutory delusions : Includes all delusions with persecutory ideation.

Well organised delusions : Illness is characterised by a series of well organised or well systematised delusions.

J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210

Delusions of influence(referred to as delusions of reference) : Events, objects or other people in patient's immediate surroundings have a special significance, often of a persecutory nature. Includes ideas of reference from TV or radio, or newspapers, where patient believes that these are providing instructions or prescribing certain behaviour.

Delusions of passivity : Include all

‘ made

’ sensations, emotions or actions. Includes all experiences of influence where patient knows that his own feelings, impulses, volitional acts or somatic sensations are controlled or imposed by an external agency.

Primary delusional perception : The patient perceives something in the outside world which triggers a special, significant relatively non-understandable belief of which he is certain and which in some way is loosely linked to the triggering perception.

Thought insertion : Patient recognises that thoughts are being put into his head which are not his own and which have probably or definitely been inserted by some external agency.

Thought withdrawal : Patient experiences thoughts ceasing in his head which may be interpreted as thoughts being removed or stolen by some external agency.

Thought broadcast : Patient experiences thoughts diffusing out of his head so that they may be shared by others or even heard by others.

Thought echo : Patient experiences thoughts repeated or echoed in his head or by a voice outside the head.

Third person auditory hallucinations : Two or more voices discussing the patient in the third person.

Running commentary voices : Patient hears voice(s) describing his actions, sensations or emotions as they occur.

Abusive/accusatory/persecutory voices : Voices talking to the patient in an accusatory, abusive or persecutory manner.

Deterioration from premorbid level of functioning :

Patient does not regain his premorbid social, occupational or emotional functioning after an acute episode of illness.

Lack of insight : Patient is unable to recognise that his experiences are abnormal or that they are the product of anomalous mental process, or recognises that his experiences are abnormal but gives a delusional explanation.

Family history of schizophrenia : Definite history of schizophrenia in first or second degree relative.

Any negative symptoms : Any one or more of catatonia, blunted affect, negative thought disorder, deterioration.

209

References

Allardyce, J., Morrison, G., Van Os, J., Kelly, J., Murray, R.M.,

McCreadie, R.G., 2000. Schizophrenia is not disappearing in

Southwest Scotland. British Journal of Psychiatry 177, 38

–

41.

Allardyce, J., Boydell, J., van Os, J., Morrison, G., Castle, D., Murray, R.M.,

2001. A Comparison of the incidence of schizophrenia in Rural

Dumfries and Galloway and Urban Camberwell. British Journal of

Psychiatry 179, 335

–

339.

Andreasson, S., Allebeck, P., Engstrom, A., Rydberg, U., 1987. Cannabis and schizophrenia. A longitudinal study of Swedish conscripts. Lancet

2 (8574), 1483

–

1486.

Arendt, M., Rosenberg, R., Foldager, L., Perto, G., Munk-Jorgensen, P.,

2005. Cannabis-induced psychosis and subsequent schizophreniaspectrum disorders: follow-up study of 535 incident cases. British

Journal of Psychiatry 187, 510

–

515.

Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Poulton, R., Murray, R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T.E.,

2002. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. British Medical Journal 325 (7374),

1212

–

1213.

Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Witton, J., Murray, R.M., 2004. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry 184, 110

–

117.

Bersani, G., Orlandi, V., Gherardelli, S., Pancheri, P., 2002a. Cannabis and neurological soft signs in schizophrenia: absence of relationship and influence on psychopathology. Psychopathology 35 (5),

289

–

295.

Bersani, G., Orlandi, V., Kotzalidis, G., Pancheri, P., 2002b. Cannabis and schizophrenia: impact on onset, course, psychopathology and outcomes. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience

252, 86

–

92.

Boydell, J., van Os, J., McKenzie, K., Allardyce, J., Goel, R., McCreadie,

R.G., Murray, R.M., 2001. Incidence of schizophrenia in ethnic minorities in London: ecological study into interactions with environment. British Medical Journal 323 (7325), 1336

–

1338.

Boydell, J., Van Os, J., Lambri, M., Castle, D., Allardyce, J., McCreadie,

R.G., Murray, R.M., 2003. Doubling in Incidence of schizophrenia in south-east London between 1965 and 1997. British Journal of

Psychiatry 182, 45

–

49.

Boydell, J., Van Os, J., Caspi, A., Kennedy, N., Giouroukou, E., Fearon, P.,

Farrell, M., Murray, R.M., 2006. Trends in cannabis use prior to the onset of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders in south-east

London from 1965

–

1999. Psychological Medicine 36, 1441

–

1446.

Buhler, B., Hambrecht, M., Loffler, W., an der Heiden, W., Hafner, H.,

2002. Precipitation and determination of the onset and course of schizophrenia by substance abuse

— a retrospective and prospective study of 232 population-based first illness episodes. Schizophrenia

Research 54 (3), 243

–

251.

Castle, D., Wessely, S., Der, G., Murray, R., 1991. The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965

–

1984.

British Journal of Psychiatry 171, 140

–

144.

Castle, D., Wessely, S., van Os, J., Murray, R., 1998. Psychosis in the inner city: the Camberwell first episode study. Maudsley

Monographs: Number Forty. Psychology Press.

Chen, J., Paredes, W., Lowinson, J.H., Gardner, E.L., 1990. Delta 9tetahydrocannabinol enhances presynaptic dopamine efflux in medial prefrontal cortex. European Journal of Pharmacology 190,

259

–

262.

Compton, M., Furman, A., Kaslow, N., 2004. Lower negative symptom scores among cannabis-dependent patients with schizophrenia

— spectrum disorders: preliminary evidence from an African American first-episode sample. Schizophrenia Research 71 (1), 61

–

74.

210 J. Boydell et al. / Schizophrenia Research 93 (2007) 203

–

210

Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, L.J., Ridder, E.M., 2005. Tests of causal linkages between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms. Addiction

100 (3), 354

–

366.

Grech, A., van Os, J., Jones, P.B., Lewis, S.W., Murray, R.M., 2005.

Cannabis use and outcome of recent psychosis. European Psychiatry

20, 349

–

353.

Hall, W., Degenhardt, L., 2004. In: Castle, D., Murray, R. (Eds.), Is there a specific

‘

Cannabis Psychosis

’ in Marijuana and Madness. Cambridge

University Press, UK, pp. 89

–

100.

Henquet, C., Murray, R., Linszen, D., van Os, J., 2005a. The environment and schizophrenia: the role of cannabis use. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31

(3), 608

–

612.

Henquet, C., Krabbendam, L., Spauwen, J., Kaplan, C., Lieb, R.,

Wittchen, H.U., van Os, J., 2005b. Prospective Cohort Study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis and psychotic symptoms in young people. British Medical Journal 330 (7481), 11.

Johns, L.C., Cannon, M., Singleton, N., Murray, R.M., Farrell, M.,

Brugha, T., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., Meltzer, H., 2004. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported psychotic symptoms in the British population. British Journal of Psychiatry 185, 298

–

305.

McGuffin, P., Farmer, A., Gottesman, I., Murray, R., Reveley, A., 1984.

Twin concordance for operationally defined schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 41, 541

–

545.

McGuffin, P., Farmer, A., Harvey, I., 1991. A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Archives of

General Psychiatry 48, 764

–

770.

McGuire, P., Jones, R., Harvey, I., et al., 1995. Morbid risk of schizophrenia for relatives of patients with cannabis associated psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 15, 277

–

281.

Rossler, W., Riecher-Rossler, A., Angst, J., Murray, R., Gamma, A.,

Eich, D., Van Os, J., Gross, V., in press. Psychotic experiences in the general population.

Semple, D.M., McIntosh, A.M., Lawrie, S.M., 2005. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. Journal of Psychopharmacology 19 (2), 187

–

194.

Smit, F., Bolier, L., Cuijpers, P., 2004. Cannabis use and the risk of later schizophrenia: a review. Addiction 99 (4), 425

–

430.

Soyka, M., Albus, M., Immler, B., Kathmann, N., Hippius, H., 2001.

Psychopathology in dual diagnosis and non-addicted schizophrenics

— are there differences? European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 251, 232

–

238.

Spitzer, R.L., Endicott, J., Robins, E., 1978. Research diagnostic criteria : rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 35, 773

–

782.

Thornicroft, G., Meadows, G., Politi, P., 1992. Is

“ cannabis psychosis

” a discrete category? European Psychiatry 7, 277

–

282.

Van Os, J., Castle, D.J., Takei, N., Der, G., Murray, R.M., 1996.

Psychotic illness in ethnic minorities: clarification from the 1991 census. Psychological Medicine 26, 203

–

208.

Van Os, J., Bak, M., Hanssen, M., Bijl, R.V., de Graaf, R., Verdoux, H.,

2002. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. American Journal of Epidemiology 156 (4), 319

–

327.

Wing, J.K., Hailey, A.M., 1972. Evaluating a Community Psychiatric

Service: The Camberwell Register 1964

–

1971. Oxford University

Press, London.

Zammit, S., Allebeck, P., Andreasson, S., Lundberg, I., Lewis, G., 2002.

Self reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. British Medical Journal

325 (7374), 1199.