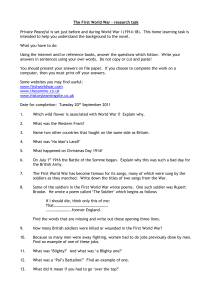

The Reality of Return: Exploring the Experiences of World War One

advertisement