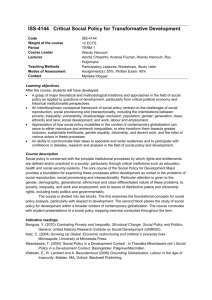

Global Inequality Beyond the Nation State

advertisement

Global Inequality Beyond the Nation State1 Thomas Schwinn Chair of Sociology I University of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt (approximate word count: 9,300) 1 Correspondence to Prof. Dr. Thomas Schwinn, Chair of Sociology I, University of Eichtaett-Ingolstadt, Ostenstr. 26-28, 85072 Eichstaett, Germany. E-mail: thomas.schwinn@ku-eichstaett.de 1 Abstract The impact of globalization on the structures of social inequality is controversial in current debates. Indeed, research focused on particular nations is being challenged by globalists. Social inequality raises the problem of order and so far this has been solved in the framework of the nation state. The reasons for and against a national and a global solution are presented. Which institutional equivalents of national systems of social equality and inequality can be found at the global level? Furthermore, the premises for the formation of globalized social structures across nations are discussed and the degree of the global structuring for different classes is investigated. A closer look is taken at the quickly developing middle classes in Asia and the commonalities with and differences to their respective western classes. The paper closes with some thoughts for solving the dispute between “methodological nationalists” and “methodological globalists” in the field of social inequality. 2 Discussions about globalization do not leave the sociology of inequality unaffected. However, this field of study is not particularly well-prepared to deal with the challenges that globalization brings with it. Indeed, many bemoan the fact that there is a dearth of theoretical concepts dealing specifically with the structures of global inequality (Breen and Rottmann 1998; Beck and Grande 2004: 258ff.; Kreckel 2004: 322; Müller 2004: 39). In this context, three problems can be distinguished, which are at the core of “global social inequality.” The first of these is the effects of globalization on intranational social structures and the social welfare state (e.g. Müller and Scherer 2003). Second, there is the social inequality that exists between nations and states (e.g. Berger 2007). Finally, there is the transnational structure of inequality across nations (e.g. Heidenreich 2006). Of these three questions, it is the third one which has received the least attention, which is why there is so little information to be found about it. This situation is certainly related to the framework of analysis employed by hitherto existing theories and studies of inequality which are delimited by the nation state. Comparisons between countries do not necessarily go beyond the scope of this framework. In fact, the units of analysis are hardly broken down for a transnational perspective, meaning that that which is “global” remains a theoretical factor that is under-analyzed and that is merely interesting insofar as it is an “external factor” when looking at national social inequality structures. World systems theories and globalization theories offer no assistance in this matter. The variations developed in Bielefeld (Luhmann)1 and Standford (Meyer) were largely worked out without relation to global structures of social inequality. However, these global structures of inequality are at the core of the economic world systems theory (Wallerstein), although this core is being dissolved by the development of many nations, especially Asian ones (Pohlmann 2002: 195ff.). Thus it is especially the critique of this paradigm (Hack 2005) that should serve as a warning not to replace a “methodological nationalism” with a “methodological globalism” all too quickly. On the other hand, the sharp polemics from Goldthorpe (2003), for example, about globally oriented theories of inequality also hinder an adequate approach to the subject. While there may be good reasons for the continuing focus on the nation state in studies of inequality, these reasons must be developed and made clear. This, however, is not happening satisfactorily. At present, it seems that this field of study is repeating what has happened in the last two decades between individualization theorists and class theorists in Germany, namely that “nationalists” and “globalists” have not been able to reconcile their differences and thus busy themselves with deconstructing the ideas of the other group.2 Such a constellation makes it difficult to give a differentiated assessment of the problems. The role of 3 the nation state is being judged controversially in the current debate about global inequality, and I will develop this topic in such a way as to be able to connect it to the framework of national inequality studies and to be able to open the scope for global structures that transcend national boundaries. In order to do so, it will be determined where and in how far global developments transcend the framework of nation state inequality (1 and 2). In the process, the appropriate units of reference and evaluation for social inequality will be explored: Which social differences and units have existential meaning for people? What is the socio-cognitive framework within which actors perceive a higher or lower, better or worse position? Do normative benchmarks and expectations change with globalization? Do structural developments coincide with patterns of actors’ perceptions or are there irregularities? Finally, I will outline how insights into studies of inequality until now can be transferred to analyses with a global focus (3). 1. The Controversial Role of the Nation State in the Globalization Process The nation state solved and continues to solve various problems of order resulting from social inequalities by legitimizing various aspects of equality and inequality, delimiting the unit of distribution and the political arena for conflict, and finally, by regulating meritocratic principles, in particular standardizing educational certificates, and claims to the welfare state. But how does globalization change the ability of nation states to cope with problems of social inequality? This is a question that has been assessed controversially. One answer to this question sees the increasing loss of meaning of the nation. The idea of a “world society” is based on the potential of differentiated institutions to become universal, a phenomenon which is being forcefully developed at present. The economy and science, for instance, rest on codes and actions that cannot stop at national borders out of principle. Thus the relatively stable constellation of institutions from the decades following the Second World War are changing. Back then, the integration of individual institutions into the nation state were at the fore. One central task was the embedding of the economy in the ensemble of institutions while wresting external thoughtfulness and national solidarity from it. Today, however, it is more about reconciling the formerly institutional segments of the nation state with comparable ones in other countries (Streeck 2001: 34ff.). It is not so much the question how the German education system, job market, welfare state, legal system, family structures, etc. fit together that is central to the formation of institutions, rather it is how, for example, German educational institutions and universities can be adjusted to fit European and international standards. The focus of institutional coordination is being moved from a national to a transnational plain. Seen from a systems theory standpoint, the institutions are less parts of the 4 national social system than they are parts of a global system. The relationship of power between political and economic interest groups are being altered with this new pattern of differentiation. State responsibilities are seen less today as taming the market than they are as supporting the market. Hence, the ability to reconcile and align institutions with national aims and ideas is ebbing. Globalization is changing the national patterns of differentiation and thus also the conditions for structuring social inequality. The nation state, within whose borders inequality structures have been cultivated until now, is becoming “functionally incomplete” (Streeck 1998). An adequate job market and a state pool of resources requires a reliable national presence of capital and production. Power structures between capital and employment as well as politics have been shifted in favor of capital. Employers’ ability to create conflict and obstruct goingson is increasing because they can threaten to change production locations, which would mean removing a service from the state. But this is not an option for employees or politicians. The relation between profits and wages is moving further apart and the taxability of capital is being reduced. Public expenditures for infrastructure and social security must increasingly be paid for by employees and consumers. Social policy is less justified by whether it reduces the gap between social positions than it is by whether it increases economic competitiveness.3 The market value of social peace decreases with the reference to countries in which there is no codetermination, the welfare state is considerably less expanded, and no strikes disrupt corporate freedoms. The national framework not only loses its economic but also its political and legal completeness. Certain political spheres, like monetary politics, are carried out at the EC level, thus diminishing the freedom of national actions. Moreover, the addressee for the articulation and assertion of the interests of intermediary groups is unclear. The other answer to the question sees the future of the nation state in a less dire situation. The degree of global openness of a country is viewed in light of its dependency on interior social inequality structures. Social inequality is thus the independent variable, whereas economic globalization is the dependent variable (Rieger and Leibfried 1997; Fligstein 2000; Vobruba 2000). The national experience that the regulation of social inequality is a “forth factor of production” is supposed to be applicable to globalization as well. Economic globalization puts enormous pressure to modernize on societies and produces more inequality. By making relative changes to productivity, industries that are no longer competitive and also wages start a downward spiral. “Work,” however, is not a passive but rather an active factor in this scenario. The more economic globalization threatens the standard of living of individual groups, the more these groups oppose the opening of the national economy. The cushioning of 5 inequality risks offered by the social welfare state creates a situation in which affected social groups need not perceive the movements, structural changes, and economic cycles of open foreign trade as an immediate danger to their situation. Historically, there is a connection between the dismantling of economic protectionism and the development of the welfare state. Indeed, as Rieger and Leibfried say: “The more the politics of the social welfare state create prospects for a safe future beyond the market, the more possible it becomes to open foreign trade. The functional specialization of social policy in the social welfare state thus renders foreign trade protectionist policies superfluous, because both have the same objective: securing income and a job.” (1997: 776). Active participation in the globalization process has hitherto been limited to those countries in which the consequences of globalization have been absorbed by social policies (Fligstein 2000). The degree of involvement in the global economy and the openness to foreign trade on the one hand and the size of the federal budget on the other hand are linked. Even the success of development in Taiwan and South Korea were steps of economic evolution as well as steps towards a social welfare state. The example of the United States shows that economic globalization is not generally associated with an expansion of interior social inequality. Its national economy exhibits less dependency on the global economy while at the same time showing a big gap in standards of living. In Germany, the situation is exactly the opposite. In light of these two schools of thought, we are faced with a dilemma: “Globalization requires social policies for its success, but successful globalization subverts national welfare states.” (Vobruba 2000: 172). The processes of struggling for power between interest groups will thus become more prone to conflict. When the pool of resources becomes smaller or at least does not grow to the degree that it has had in past decades, the ferocity of distribution fights increases. The status quo orientation of interest groups and social policies will likely increase rather than decrease in relation to the degree of globalization. “The comparison of the development in the United States and western European countries shows that the ability to make sociopolitical changes decreases with increasing globalization pressure. It is especially the extensive restructuring of American welfare benefits in 1996 – the states’ giving up of the guaranteed right to welfare benefits, the introduction of limitations to the length of time people can receive such benefits, and the shift of core competencies to individual states – that shows that the comparatively low globalization pressure found there eased the institutionalization of social welfare policies with far-reaching effects on distribution, while the comparatively high globalization pressure found in Germany seems rather to prohibit corresponding changes in the sociopolitical status quo” (Rieger and Leibfried 1997: 791). 6 These two schools of thought assume that there are contrary cause-effect relationships between ideas and structures. The first pool of research implies that the legitimation discourse linked to social inequality follows changing social structures and adapts to them: Reduction of the necessity to be legitimated coupled with the actual sinking of resources and the ability to create conflict. In contrast, the other pool of research assumes that there is a constant, high expectation to be legitimated despite changing structures. What the one group of researchers see as an independent variable, the other group deems a dependent variable and vice versa. Theoretically speaking, neither viewpoint is very plausible. Without assuming a direct causeeffect relationship and a synchronic development, factors are generally both caused by and a cause of their situation. “With regard to quantitative indicators, the change of work relations and welfare states limps along behind structural economic changes in companies and is only affected by it to a limited degree. The path-dependent hybridization of these institutions follows a logic that is influenced by strong interests in the durability of hitherto-existing rules, the attitude of organization members and voters, and by the diagnosis of problems by political elites” (Armingeon 2005: 456). This empirical result can be expected from a differentiation theory standpoint. Politics and the economy follow their own logic, which, however, is not immune to changes in their contexts. The institutionalization of social inequality, which is essentially carried out in work relations and the welfare state, takes place in the political arena. The conflict process takes place there with recourse to legitimizing ideas. In this political discussion, the necessity for social inequality to be legitimated levels off at a certain level. But it is a political dispute, and while it receives considerable input about economic problems, it is not determined by it. A change in the institutionalization of social inequality has been observed, which in the above-mentioned quotation has been called “path-dependent hybridization.” While one school of thought concentrates more on the intensification of social inequality caused by the economy, the other focuses on interior political processes. And although both emphases are important, as isolated perspectives they are too short-sighted. A further problem in the controversy surrounding national versus global social inequality is the ever-diffuse understanding of the notion and concept of what is “global,” of which there is both a weak and a strong version. If nations are taken as central units of analysis, the global aspect is not denied, but it is rather weak. To begin with there are good empirical reasons for a study of inequality not to lose track of nations. “Inequality within a country accounts […] for only a quarter to a third of all global income inequality. The components of world income inequality between societies is thus two to three times greater than the components within a nation […] Consequently, we can explain about 70% of the variance of individual incomes 7 worldwide based on a single piece of information about individual people, namely in which country they live” (Firebaugh 2003: 366; see also Berger 2005). Studies that compare countries especially emphasize intranational structures, which have advantages and disadvantages in the global playing field (Blossfeld 2001; Mayer 2001; Goldthorpe 2003; Müller and Scherer 2003): the degree to which the social welfare state is present, the regulation of the job market, the structure of the education system, etc. Globality is reduced to mere external challenges for which different national solutions can be found and to which diverging answers can be given. However, this area of research has no interest in global structures. Generally, developed countries are compared with a focus on their various structures, which are not made homogeneous by globalization. The longevity of countryspecific patterns of institutional differentiation despite global tendencies of individual systems is due to the fact that these institutions create interwoven arrangements with a high degree of mutual complementation. The specific manner of coordination of these different institutions leads to country-specific packages of institutions (Blossfeld 2001: 240ff.; Hollingsworth 2000; Mayer 2001): between education and employment systems; between family structures, the job market, and the welfare state; between religion, politics, and the law, etc. This high degree of complementation and interlocking of nationally-grown institutional patterns gives rise to a certain amount of rigidity, which can make it difficult for individual institutions to react flexibly to global demands. National institutions are not just extensions of world systems whose changes could be reproduced with the same logic everywhere. The concrete embedding of an institution in a national framework of institutions determines how it can be connected to global processes. National variations of institutional constellations are reflected in various social inequality structures (Breen and Rottman 1998; Blossfeld 2001; Müller and Scherer 2003). Globalization leads to a growing service proletariat in countries with open employment structures and a liberal welfare state. In countries with relatively closed employment structures and a well-developed welfare state globalization leads to an increase in the gap between a highly secure, high-income service class and a growing marginalized group that is somewhat supported and accommodated for by the welfare state but vainly tries to find employment (Esping-Andersen 1993; Blossfeld 2001). Inequality studies that compare countries bring important findings to light but do not have their own theoretical framework to grasp global structures (Kreckel 2004: 322). This is also true of “variety” studies dealing with different forms of capitalism, the social welfare state, education, etc. The conceptual weakness of global factors in such studies has to do with the method of comparison, which generally looks for differences and looks for comparable cases 8 from the very beginning. Even in such studies that aim at creating a ranking of countries in which these countries are positioned according to different criteria, like social inequality (for instance gross national product per capita), the main burden of explanation lies with the internal factors of a particular country. The context, “global challenges,” remains but a pale backdrop. World society theories promise clarification of global structures. These theories are dominated by a strong version of what “global” means. In the newer systems theory, for example, world society itself is the source of developmental differences. “The inequality argument is not an argument against but rather an argument for a world society. […] It is precisely the different levels of development in various parts of the globe that demands a social theory explanation, and this cannot happen according to the thousand-year-old pattern of ‘diversity of peoples,’ rather the unity of the global system that creates these differences must serve as the starting point” (Luhmann 1997: 162; see also Stichweh 2000: 12f., 31f.). According to this theory, it is not primarily internal factors of a country that lead to differences, but rather the emerging level of the world system. While the structures of this system are attached to regional and national conditions, these conditions are transformed into internal differences of the world system itself. Unfortunately, this assumption lacks a corresponding empirical foundation, which could make it plausible that all country-specific and region-specific variations follow a kind of global logic.4 On the one hand, global structures are underexposed in studies on inequality that focuses on countries and that compares these countries to one another, and on the other hand, the assumption of a “world society” underestimates the national framework, which interferes with global impacts. Inequality studies that compare countries generally compare developed countries with one another. This is appropriate for this particular method of comparison, because the cases consulted should not differ in too many aspects. Thus, however, enormous inequalities found in a global setting are lost. For such inequalities a completely different type of theory has been necessary until now: world systems theory, dependence theory, or modernization theory. Thus national and global inequality cannot be explained by the same theory. This is a dissatisfactory state of affairs which cannot be resolved with newer world society theories. Although such world society theories do overcome the economic determinism of Wallerstein’s world systems theory, a theory of how national and global inequalities can be conceptually integrated has yet to be developed. 2. The Question of Transnational Inequality Structures This paper cannot claim to offer such an all-encompassing theory. Rather I would like to approach the task by focusing on a specific perspective. Social inequality poses a problem of 9 order that has heretofore been solved by the nation state. The discussion about the role of the nation state in the globalization process deals with the question of whether the nation state is still capable of offering an institutional framework for inequality structures (Section 1). The question that has not been answered in this controversy is whether and in how far global inequality structures can develop outside of the framework of the nation state. It remains to be seen to what degree worldwide inequality structures can develop without a state on the global level. In the following section I will look at this problem from the viewpoint of whether transnational “world classes” or “world social strata” have developed or can develop. This particular question has received little attention in the field. But only when this question is answered can the global dimension of social inequality be understood that emerges with the disappearance of the nation state’s function to structure institutions. 2.1 Global Achievement Society The development of transnational social classes would seem to suggest itself in the abovementioned discussion which claims that there is a transition from a nationally indexed differentiation structure to a global differentiation structure. Social groups change at the relatively same rate at which economic markets, education systems, academic institutions, and legal institutions become transnational. Creating institutions activates corresponding processes of creating groups and social classes as can be seen in the historical development of nation states. But do social classes follow globalizing systems? Or is this not very likely because the reference to the nation state that creates identity and solidarity is missing in the global setting? In the section “Klassen, Stände, Parteien” in his book Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (Weber 1980: 531ff.), Max Weber differentiates between three different sources of power that serve as stepping stones for the creation of inequality structures: economic opportunities (classes), symbolic competence (status groups), and political power (parties). These three resources generally contribute to each position of inequality (see also Schwinn 2004: 22ff.). In how far can these resources be converted and used above and beyond nations, and do they establish a global achievement society that is constitutive of the distribution and comparison of life chances?5 Cultural competencies are primarily acquired today in educational institutions. The research group surrounding John Meyer (2005: 212ff.), especially, has determined that there is a global spread of educational institutions that are structurally similar. This transnationalization of the education sector means that contents and teaching methods, exams, and degrees are becoming similar around the globe. The “Bologna Process,” for instance, is aiming at degrees in tertiary education that are comparable in Europe and with degrees around 10 the world. “The explicit goal is to institutionalize an internationally standardized and ‘calibrated’ educational ‘currency’ that is recognized everywhere and that will be accepted everywhere. In this respect, a classification of the world’s population according to educational degrees across national borders is gradually becoming possible […]” (Kreckel 2004: 325). And this is just the beginning. As Hartmann (2003) has ascertained about the creation of a European elite, their career paths are still largely determined by national educational institutions. This is true for managers, politicians, branches of the civil service, legal professions, and the military. Nevertheless, the thorough academization of privileged positions will likely lead to a meritocratic achievement ideology in upper professional levels within which people are conscious of the value of university degrees despite national variations in educational institutions. The enormous effort east Asian countries put into achieving an education will cause the academic market and the awareness for the value of convertible university degrees to grow. The widespread practice of ranking education standards, for example PISA, will further cement this resource as a criteria for vertically classifying the world’s population. A person’s level of education must be converted into economic capital in order to have a durable influence on their life chances. First signs of a structural transnationalization of economically caused strata can be seen, like, for example, the worldwide usable knowledge of information technology specialists (Weiß 2002). To the same degree that this particular branch is becoming more global and opening up more branch offices in ever more countries, corresponding occupational competencies are freeing themselves from national ties. The same holds true for qualified academicians for whom European, American, and Asian universities and research facilities constitute a global academic market from which they can pick and choose. Along with the internationalization of political institutions and organizations corresponding political and administrative careers are developing that transcend national borders. Such a phenomenon has long been observed in competitive sports. Mixed national teams can be seen everywhere in professional soccer, for example. For this group of workers with usable global market qualifications, national hurdles are often nothing but a mere technicality. Work permits, for example green cards, are readily given to Indian software specialists and professional South American soccer players. But these positively privileged classes of employees must be distinguished from negatively privileged classes of employees. Under-qualified and low-qualified people find themselves exposed to a world market whose pressure to become mobile and migrate becomes stronger the worse poor circumstances are absorbed by the social state. The large horde of international migrant workers proves this. 11 National border regimes protect themselves from this surplus of labor. Positively and negatively privileged people owe their social positions to a certain extent to the world market, which creates a global context of supply and demand and a pressure for global comparison. This can be seen for example when European academicians compare their situation with their American counterparts or when industrial workers are reproached with East European or Asian wages. The world market is a structural option for those workers who are positively privileged, whereas for negatively privileged people it is a structural constraint. Those groups of employees that have little or no market power or have qualifications that can be easily replaced are faced with the comparison of low wages in other countries. The principle of giving people equal wages for equal work has a positive influence on the income of those who are especially qualified or belong to a highly sought after group of employees. A couple of years ago, Lufthansa pilots went on strike by drawing attention to the much higher wages their colleagues made working for airlines in other countries. Everywhere where members of such groups of workers are in close contact with one another or even work in the same organization the probability that such transnational comparisons will be made rises, like between managers of companies which have local branches in different countries or when companies in different countries are merged. This also holds true for transnational political organizations and administrations. In 2004 some members of the European Union parliament started an initiative to adjust parliamentary salaries of EU parliamentarians (Beck and Grande 2004: 266ff.), which differ by as much as tenfold between colleagues from different countries. These examples also make it clear that the world market and transnational structures do not automatically lead to equal pay for similar jobs: it is only a structural potential that can be used by the actors in their strategies of interest. The idea of being paid the same amount for doing the same job must be activated, blocked, or watered down in conflict situations. Even where unequal pay has been defended for equal work, the effort needed to justify and defend this difference has become greater. Globalization not only has structural consequences, but it also serves as a pattern of legitimation. Referring to global competition serves as a justification for lowering personnel costs, reducing social welfare state benefits, or increasing managers’ salaries. It is doubtful whether these measures can always be ascribed to structural constraints, but accepting such arguments as true offers some actors the privilege of being able to enforce their programs. 2.2 Global Orientations Apart from analyzing global position criteria and global achievement criteria (objective class), global patterns of perception and conflict (conscious class) must also be analyzed. Money is 12 an abstract gauge on which differences can be easily read and with which people’s material life chances can easily be compared. Transnational inequalities are thus generally measured according to differences in income (Kreckel 2004: 326). Highly qualified income groups can be found in the same system of statistical classification as unqualified migratory workers or peasants in the third world. The statistical transnational classification of the global population according to disposable income offers important information about objective differences in living conditions. From a sociological standpoint, however, this information is dissatisfactory so long as it remains unclear in how far statistical differences correspond to real social groups. Can it be assumed that “conscious world classes” will emerge at the transnational level as has been the case with national experiences? Marx expected this to happen as is evident in his call for the proletariat in all countries to unite. The process of creating conscious inequality groups occurs in various steps. To begin with it must be asked if a collective consciousness with corresponding patterns of perception develops across nations when people are in objectively similar positions. Only then can the chances of the development of transnational structures of conflict that develop from social inequality be assessed. Are people conscious of a global social inequality? Do they see themselves as part of an international system of strata, and does their positioning themselves in such a system influence their assessment of their own situation? These questions can be looked at according to the action and orientation relevance of gaps in prosperity between international reference groups (Delhey and Kohler 2006: 340). Research into global inequality has little to offer as a solution to this problem. “Herein lies the sociological defect of a statistically designed concept of world society: It ignores all social contexts in which inequality develops or in which experiences of inequality can evoke social disintegration, political conflict, or even solidarity. For lower classes in Latin America it is irrelevant whether Chinese coastal regions experience extraordinary growth. It is also little consolation for America’s working poor that they are better off than miners in Ukraine from an absolute standpoint. A number of factors that can predict trends but cannot be attributed to one compact cause, namely globalization, interfere in the inequality of the world’s population. For the time being researching global inequality remains an innovative field of experiments for collecting new data and statistics. Thus far, developing theories has no place in this field” (Müller 2004: 39). Social inequality presupposes a comparative unit according to which people can gauge their higher or lower position and their life chances. Under what conditions does a change from a national to a global framework take place as seen from an academic and a lifeworld perspective? Developing sociological theories is closely linked with ‘the moving light of great 13 cultural problems’ (Max Weber). Kreckel (2006) presumes that the methodological nationalism of inequality research has to do with the treatment of and solution to the social question within national boundaries since the 19th century. Though the global social question has been on people’s minds as an ideal for a long time, as long as it is not seen as an effective idea that can be realized, the sociological analysis of social inequality will not overcome its national restrictions. Accordingly, the discussion about global inequalities has been strongly influenced by economic methods and ways of thinking, which abstract from cultural, historical, and social conditions and concentrate on bare economic indicators that are measurable in money. Kreckel sees the beginnings of a global spread of a basic norm of worldwide equality and politics dealing with poverty and inequality through international organizations such as the United Nations, UNCTAD, UNDP, and the world bank as well as through international NGOs in recent years. The global social question is gaining political attention and is becoming a topic of sociological studies. Choosing a global framework for comparison has both normative and cognitive prerequisites. People need to have access to information about the living conditions in other regions and countries. The expansion of western standards of consumption through mass media and tourism into all corners of the earth establishes a certain level of expectations in people’s minds that becomes relevant for orienting and acting in combination with global norms of equality and justice. The stream of migration from underprivileged countries into wealthy countries show that many people compare their standard of living to that of others on a global basis. Naturally, these global comparisons are not symmetrical. Upward comparisons are more important than downward comparisons (Delhey and Kohler 2006: 352ff.). Looking up has a stronger negative effect on a person’s satisfaction with life than looking down has a positive effect. Comparisons that transcend borders influence a person’s satisfaction with their own situation more when rich nations serve as a benchmark. Moreover, less affluent countries are generally less inward-oriented than affluent ones. Thus the working poor in America do not compare themselves with lower classes in Latin America or miners in Ukraine. And when these two groups look at the United States, they do not look at the corresponding underprivileged class there, rather they look at the standard of living prevalent in the middle class: The orientations of structurally analogous underprivileged strata do not meet. 2.3 World Classes In order to specify the degree of transnational social structuring it is helpful to look at insights into class theory, which differentiates different steps of class structuring (Giddens 1979: 129ff.), and then to ask whether the conditions for such a development exist at the global 14 level. Giddens differentiates between “class awareness” (“Klassenbewusstheit”) and “class consciousness” (“Klassenbewusstsein”). With class awareness he means the common lifestyle that grows out of a particular social stratum and similar attitudes that are shared by the members of a particular class. Political consciousness of conflict requires class consciousness, in which case the actors have more or less drawn up a mental map with which they can determine differences and clashes of interest. This is necessary for political action. If this distinction is adhered to, it is possible as a first step to look for common lifestyles and mindsets that transcend national borders. Meanwhile, some research results about middle classes in non-western regions and cultures have been presented. In the success of modernization, for example, the emerging middle classes in Asia show western-like lifestyles and patterns of consumption (Robinson and Goodman 1996; Hsiao 1999; Chua 2000; Schwinn 2006b: 209ff.). Education and income levels are rising there and the portion of disposable income that is not necessary to secure a minimal existence is increasing. With the necessary spending power, the middle classes are developing a way of life that is being shown them by the cultural industry and the mass media. In addition, the participation of women in the education and job sectors is growing, which is changing patriarchal values and traditional family structures. Similar lifestyles that are common across countries and cultures are growing out of comparable levels of modernization. These lifestyles are typical of the middle class, which is molded by conditions of production and consumption of capitalism, which is spreading around the globe. But the structuring of classes remains on the step of lifestyles and mindsets and does not develop further into a shared political consciousness, because the necessary conditions for such a development are missing. For one thing, middle classes have a strong individualistic orientation and place more emphasis on individual mobility than on that of the whole class. Another reason for this lack of development is that the conditions for transnational networking are not really given – conditions that are present in a national context such as a common language, communication in organizational and urban infrastructures, and a national public sphere. Furthermore, there is a lack of interest in creating a common global conflict group. Under the harsh conditions of the world market, the middle classes owe their standard of living to the competitiveness of their national economies and national industries, which offer them employment opportunities. Hence, there is likely to be more consent with local employers than there is to be solidarity with middle classes in other countries. This constellation also applies to multinational companies with branches in several countries. It is conceivable that employees of these different branches could develop common interests 15 across nations that are opposed to those of top managers. In light of the continual relocation of production facilities, however, it is more likely that the solidarity employees feel with their particular branch of the company is greater than that felt with related staff in other countries, which is something that labor unions have already experienced at the national level. Thus the middle classes are lacking the conditions and interests for a thorough social structuring at the global level. Apart from economic and strategic considerations, there are also regional cultural and political conditions that are working against the development of a politically self-conscious transnational middle class. Cultural and political factors are always present in addition to economic factors when new classes are developed. Middle classes in Europe are associated with politico-democratic aspirations and expectations of emancipation. These virtues of civil society are less present in fast-growing Asian middle classes because their development is taking place under other conditions. In eastern Asia Confucianism plays a role (Rüland 1997: 95f.; Holzer 1999: 90ff.; Hsiao 1999). The difficulty in mobilizing such societies is linked to the high esteem placed on the Confucianist values of harmony, unity, and consensus and a much greater tolerance of authorities and hierarchies. The term “politics” in its meaning of controversy, critique, and opposition has a bitter aftertaste. Consequently, there is a widespread inclination to be apolitical and to flee to the private sphere and consumption as well as a relatively low voter turnout in comparison to Europe, even in strongholds of urban middle classes. The new middle classes in East Asia represent a globally unified lifestyle and consumption style facilitated by the economy. But this does not mean that it is possible to presume political values or virtues of civil society as is typical of middle classes in the West. The same also holds true for Indian middle classes (Bieber 2002: 227ff.). The historical inheritance of the Hindu caste system plays a role in shaping the attitudes of economically successful groups. The traditional lack of collective social responsibility and solidarity above and beyond one’s own caste leads to an unrestrained drive for profit and a distinct tendency to put one’s own wealth on display, which is not stopped by any form of social responsibility or public spirit. The contentious and uncertain role of Asian middle classes as proponents of a politicodemocratic culture is also explained by distinctive sociopolitical features (Robison and Goodman 1996: 2ff.; Rüland 1997:91ff.; Hsiao 1999). The development of capitalism in East Asia was initiated by the state and is carried out by the state. The leeway for creating and pluralizing social interest groups is limited. For one thing, the middle classes do not have much interest in becoming more democratic, and in some countries they have come to terms 16 with authoritarian regimes. They largely owe their rise and status to extended state activities, and they are willing to tolerate non-democratic political institutions as long as they are guaranteed an increase in their affluence. This solidarity with authoritarian state elites can even been found where demands from lower classes, such as farmers and industrial workers, are parried or where there is a lack of support for protest movements against the ecological and social effects of unhindered economic growth. Political authoritarianism and political apathy also result from another historical constellation in which Asian middle classes are developing in contrast to western middle classes. The late industrialization and modernization of East Asia means that middle classes and working classes are developing at the same time, while in the West the middle classes followed the working classes after a period of time. Asian middle classes are still in the process of developing and being shaped. They are enjoying their relatively quick rise to affluence by looking back on the working class and peasant status they have left behind them and their relative standing to lower classes. Right now it seems unclear whether democratization will affect their achieved status under such conditions of rapid change. “Chinese with money – those who might be expected to demand more democracy – fear they would be victims, not beneficiaries, of a one-person, one-vote system. Some 250 million people in China’s bustling cities and thriving coastal provinces are vastly better off now than they were a decade ago – but the other 900 million Chinese are peasants, eking out a life in medieval-like conditions. Would the rich give control over their lives and destiny to the poor? […] Thus, many of China’s newly rich prefer the stability of the old system to the prospective turmoil of an electoral free-for-all” (Brauchli, quoted in Rieger and Leibfried 2004: 222). This nonsimultaneous development of classes in different regions of the world is a further reason why it is unlikely that a politically articulate world middle class will develop. On the bottom rungs of the social ladder it is safe to assume that there are at least potential common transnational interests. In contrast to the middle classes, underprivileged people hardly profit from world market competition. But their common interests are not backed up by a corresponding organization or conflict potential. In addition to the impeding structural circumstances already mentioned in relation to the middle classes, there are also aggravating ethnic differences. How should Marx’s call for the proletariat of all countries to unite be realized in the global arena if this is not even possible at the national level? The groups immigrating into other regions and cultures do not come face-to-face with fellow class members who are willing to show solidarity, rather they face xenophobia. Processes of migration have created a global lower class in many countries which is concentrated in 17 particular areas. But ethnic, cultural, and language differences prevail over collective economic interests. After all, the underprivileged do not have a good conflict potential, they do not posses sought-after qualifications, and they can be replaced easily. The prerequisites for class formation are most auspicious for a small segment of privileged professional groups. Diplomats, managers, politicians, bureaucrats, scholars, etc. necessarily have close contact with colleagues from other countries who are in similar strata because of their occupations. Huntington (1998: 78) calls this the “Davos Culture,” named after the Swiss town Davos in which the world economic forum meets, which he says has developed in these circles. A global elite is characterized by common intellectual standards based on similar academic training. By meeting recurrently at symposia and conferences and by working together in international organizations and companies, the behavior and language of these people become similar. The conditions for finding commonalities and related interests on a global level can thus be found: a shared language, intellectual abilities, and communication. Through organizational integration and regular participation in the culture of conferences and diplomats, their heterogeneous cultural and social backgrounds give way to a common orientation. This is necessary to meet institutional demands that these professional groups have to meet. The experiences they have in this process are of course also useful for the formulation and enforcement of the interests of this class. The demands for more money made by Lufthansa pilots and EU parliamentarians have already been mentioned. Apart from this, Michael Hartmann sees special chances of a transnational social structuring of the European economic and administrative elite in the large similarity of social recruiting in this class. “Their common bourgeoisie background makes it easier to assimilate. The smaller the social groups are and the higher they are ranked in the social hierarchy, the easier it generally is to communicate. The best example of this is European royalty in the Middle Ages. While the European population was highly fragmented in every respect in innumerable separate groups back then, the nobility constituted a relatively homogenous group that shared a common language, and in this group marriages that transcended borders were common. Accordingly, the unification of a transnational elite will most likely happen in the upper class, which means it will affect people at the top of the economy, free professionals, and (with some exceptions) people in administrative jobs” (Hartmann 2003: 294). Common consciousness does not only come “from below,” that is from the conditions of the particular stratum, it is also induced “from above” by political institutions. Norms of equality have thus far been institutionalized in the nation state, which is the clearing unit for problems of distribution. Politics and the framework that is delimited by political institutions and public 18 infrastructure are the focus of processes of identification and identity creation. The political framework that is constructed weakly at the EU level is even becoming blurred on the global plain. Fragmented levels and arenas of decision making, which, democratically speaking, are often not legitimated at all or not enough, do not offer actors a clear focus of identification. Uncoordinated supranational law-making bodies do not create a normative security and reliability for conflict processes or adherence to results that have been achieved. The concept of intermediary interest organizations shows that they have their point of reference in political structures, where they assert their clientele’s interests, thereby playing their part in political legitimation. Today’s “world society” has no legitimation problem because it does not have a democratically elected government. Transferring the system of intermediary interest groups that are at home in the national arena to the global level does not make much sense, as there is no political addressee at the global level. 3. Principles of Order and Institutional Equivalents Whereas there are enough statistics about global inequality, there is no sociological inequality theory about this topic. The majority of studies have a comparative focus and comparable cases are generally taken from developed regions. Neither aspect supports the viewpoint on transnational connections. The common division between sociological theory and special sociology in this field of analysis also does not work. Theories about a global society largely disregard social inequality or remain mere statements of being able to explain the situation, at least in principle. This text cannot be expected to plug the theoretical holes, but it is supposed to make it clear why inequality studies have problems with this new dimension of social inequality. The nation state offers the institutional framework without which traditional inequality studies makes no sense: legitimation of aspects of equality and inequality, delimitation of units of distribution and the political conflict arena, institutionalization of conflicts, the ability to balance economic inequality and civic equality, and regulation of meritocratic principles. These institutional services are not present at the global level and it is little wonder that researchers of inequality rarely dare to approach this set of problems, as they then find themselves in uncertain territory. Consequently, they defend nationally focused inequality analyses against “globalists.” There are probably good reasons for this behavior. The problem of order is a basic question in sociology, and until now inequality theory has shown under which conditions social inequality can be put in order, namely in the nation state. It would be careless to wipe away these insights for global analyses. The national institutionalization of social inequality must first be specified before it can be determined if and what functional equivalents there are at 19 the global level. “Globalists” critique of “methodological nationalism” overshoots the target if it is ignored that the institutional principles about social inequality won in the nation state can be generalized. Thus Beck and Grande criticize the nationally focused sociology of inequality but broach exactly those problems of global social inequality for which the nation state has had to find a solution in history, for example the question of how problems of recognition and problems of redistribution can be regulated (Beck and Grande 2004: 263, 269ff., 280ff.). Equalities and inequalities must also be construed on the global level and these differences must be legitimated and “all of these questions can only be answered by political decisions” (Beck and Grande 2004: 241). It would thus help in this situation to distinguish between institutional and legitimating principles of social inequality, which are not bound to the national or global arena, and the concrete form of institutions, which vary according to level. One such example would be Marshall’s three normative principles of social equality and inequality, which more or less coalesce in the nation state so far but must be separated from one another at the global level; these are universally valid and globally institutionalized human rights but different socio-geographic units for the institutionalization of political and social rights. Even when no equivalent institutions are present at the global level, the nation state experience can help evaluate which type of inequality is developing and what the consequences of such developments may be. This text has tried to do just that. The recapitulation of national experiences in which socio-structural groups have grown in relation to political institutions is not very likely to happen in the middle term. The global level is neither a socially integrative nor a political unit. The widespread normative demands for international justice is missing the foundation of civil society and corresponding institutions. First signs of a global achievement society can be seen in certain segments of the education and job markets. The enormous objective inequalities that are produced through globalization processes do not correspond to processes of conscious class formation. The chances that statistically measurable units and differences will become socially conscious ones that lead to action are not the same for different strata, and these chances are only given for a small privileged class at the global level. Global inequality is largely an unarticulated inequality and is without conflicting interest groups and their organizations. As long as there is no democratically legitimated world political order, global inequalities are possible to a degree that would go beyond the scope of national orders. This could prove to be a stumbling block for a world order because globalization produces problems without producing the required 20 conditions for the solutions to these problems, and inequalities that find no adequate arena are inclined to erupt or produce incontrollable effects. 21 End Notes 1 This topic also plays but a marginal role in Stichweh (2000; 2005). See Beck and Grande (2004: 258), who accuse studies of inequality of being nationally “short-sighted,” or Goldthorpe’s (2003: 309) acrimonious labeling as “ globalization nonsense.” 3 For more information about Anthony Giddens’s and Tony Blair’s propagandized “third way” see Merkel 2000. 4 For critique see Schwinn 2005 and Schwinn 2006a. 5 For a similar outline see also Kreckel 2004: 324ff. 2 22 References Armingeon, Klaus. 2005. “Die Ausbreitung der Aktiengesellschaft und der Wandel des Wohlfahrtsstaates und der Arbeitsbeziehungen: Ein internationaler Vergleich.” Pp. 441-459 in Finanzmarkt-Kapitalismus: Analysen zum Wandel von Produktionsregimen (KZfSS-Sonderheft 45), edited by Paul Windolf. Wiesbaden: VSVerlag. Beck, Ulrich and Edgar Grande. 2004. Das kosmopolitische Europa. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Berger, Johannes. 2005. “Nimmt die Einkommensungleichheit weltweit zu? Methodische Feinheiten der Ungleichheitsforschung.” Leviathan 33: 464-481. Berger, Johannes. 2007. “Warum sind einige Länder so viel reicher als andere? Zur institutionellen Erklärung von Entwicklungsunterschieden.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 36: 5 – 24. Bieber, Hans-Joachim. 2002. “Zum Verhältnis religiöser und kultureller Traditionen und Wirtschaft in Indien.” Pp. 191-242 in Religion, Werte und Wirtschaft. China und der Transformationsprozess in Asien, edited by Hans G. Nutzinger. Marburg: Metropolis. Blossfeld, Hans-Peter. 2001. “Beruf, Arbeit und soziale Ungleichheit im Globalisierungsprozess.” Pp. 239-264 in Aspekte des Berufs in der Moderne, edited by Thomas Kurtz. Opladen: Leske & Budrich. Breen, Richard and David B. Rottmann. 1998. “Is The Nation State The Appropriate Geographical Unit For Class Analysis?” Sociology 32: 1-21. Chua, Beng-Huat (ed.). 2000. Consumption in Asia: Lifestyles and Identities. London / New York: Routledge. Delhey, Jan and Ulrich Kohler. 2006. “Europäisierung sozialer Ungleichheit. Die Perspektive der Referenzgruppen-Forschung.” Pp. 339–357 in Die Europäisierung sozialer Ungleichheit: Zur transnationalen Klassen- und Sozialstrukturanalyse, edited by Martin Heidenreich. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus, S.. Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (ed.). 1993. Changing Classes. Stratification and Mobility in Postindustrial Societies. London / Newbury Park / New Dehli: Sage. Firebaugh, Glenn. 2003. “Die neue Geografie der Einkommensverteilung der Welt.” Pp. 363389 in Mehr Risiken – Mehr Ungleichheit? Abbau von Wohlfahrtsstaat, Flexibilisierung von Arbeit und die Folgen, edited by Walter Müller and Stefanie Scherer. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus. 23 Fligstein, Neil. 2000. “Verursacht Globalisierung die Krise des Wohlfahrtsstaates?” Berliner Journal für Soziologie 10: 349-378. Giddens, Anthony. 1979. Die Klassenstruktur fortgeschrittener Gesellschaften. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Goldthorpe, John H. 2003. “Globalisierung und soziale Klassen.” Berliner Journal für Soziologie 13: 301-323. Hack, Lothar. 2005. “Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Totalität: Von Marx' kapitalistischer Gesellschaftsformation zu Wallersteins Analyse der 'Weltsysteme'?” Pp. 120-158 in Weltgesellschaft: Theoretische Zugänge und empirische Problemlagen, edited by Bettina Heintz, Richard Münch, and Hartmann Tyrell. Stuttgart: Lucius. Hartmann, Michael. 2003. “Nationale oder transnationale Eliten? Europäische Eliten im Vergleich.” Pp. 273-297 in Oberschichten – Eliten – Herrschende Klassen, edited by Stefan Hradil and Peter Imbusch. Opladen: Leske & Budrich. Heidenreich, Martin. 2006. “Die Europäisierung sozialer Ungleichheiten zwischen nationaler Solidarität, europäischer Koordinierung und globalem Wettbewerb.” Pp. 17-64 in Die Europäisierung sozialer Ungleichheit: Zur transnationalen Klassen- und Sozialstrukturanalyse, edited by Martin Heidenreich. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus. Hollingsworth, Roger. 2000. “Gesellschaftliche Systeme der Produktion im internationalen Vergleich.” Pp. 279-312 in Moderne amerikanische Soziologie, edited by Dieter Bögenhold. Stuttgart: Lucius. Holzer, Boris. 1999. Die Fabrikation von Wundern. Modernisierung, wirtschaftliche Entwicklung und kultureller Wandel in Ostasien. Opladen: Leske & Budrich. Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (ed.). 1999. East Asian Middle Classes in Comparative Perspective. Taipei: Academia Sinica. Huntington, Samuel P. 1998. Der Kampf der Kulturen: Die Neugestaltung der Weltpolitik im 21. Jahrhundert. Munich / Vienna: Siedler. Kreckel, Reinhard. 2004. Politische Soziologie sozialer Ungleichheit. 3rd edition. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus. Kreckel, Reinhard. 2006. Soziologie der sozialen Ungleichheit im globalen Kontext. Halle. Unpublished manuscript. Luhmann, Niklas. 1997. Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Mayer, Karl Ulrich. 2001. “The Paradox of Global Change and National Path Dependencies: Lifecourse Patterns in Advanced Societies.” Pp. 89-110 in Inclusions and Exclusions 24 in European Societies, edited by Alison Woodward and Martin Kohli. London / New York: Routledge. Merkel, Wolfgang. 2000. “Die Dritten Wege der Sozialdemokratie ins 21. Jahrhundert.” Berliner Journal für Soziologie 10: 99-124. Meyer, John W. 2005. Weltkultur: Wie die westlichen Prinzipien die Welt durchdringen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Müller, Klaus. 2004. “Ungleichheit und Globalisierung.” Pp. 27-43 in Diskurs, Macht und Praxis der Globalisierung: Reflexive Repräsentatonen, edited by Jörg Meyer et al. Münster: LIT. Müller, Walter and Stefani Scherer (ed.). 2003. Mehr Risiken – Mehr Ungleichheit? Abbau von Wohlfahrtsstaat, Flexibilisierung von Arbeit und die Folgen. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus. Pohlmann, Markus. 2002. Der Kapitalismus in Ostasien: Südkoreas und Taiwans Wege ins Zentrum der Weltwirtschaft. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot. Rieger, Elmar and Stephan Leibfried. 1997. “Die sozialpolitischen Grenzen der Globalisierung.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 38: 774-796. Rieger, Elmar and Stephan Leibfried. 2004. Kultur versus Globalisierung. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Robison, Richard and David S.G. Goodman (ed.). 1996. The New Rich in Asia: Mobile Phones, McDonald's and Middle-Class Revolution. London / New York: Routledge. Rüland, Jürgen. 1997. “Wirtschaftswachstum und Demokratisierung in Asien: Haben die Modernisierungstheorien doch recht?” Pp. 83-110 in Entwicklung: Die Perspektive der Entwicklungssoziologie, edited by Manfred Schulz. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. Schwinn, Thomas. 2004. “Institutionelle Differenzierung und soziale Ungleichheit: Die zwei Soziologien und ihre Verknüpfung.” Pp. 9-68 in Differenzierung und soziale Ungleichheit: Die zwei Soziologien und ihre Verknüpfung. 2nd edition, edited by Thomas Schwinn. Frankfurt am Main: Humanities Online. Schwinn, Thomas. 2005. “Weltgesellschaft, multiple Moderne und die Herausforderungen für die soziologische Theorie: Plädoyer für eine mittlere Abstraktionshöhe.” Pp. 205-222 in Weltgesellschaft: Theoretische Zugänge und empirische Problemlagen, edited by Bettina Heintz, Richard Münch, and Hartmann Tyrell. Stuttgart: Lucius. Schwinn, Thomas. 2006a. “Die Vielfalt und Einheit der Moderne. Perspektiven und Probleme eines Forschungsprogramms.” Pp. 7-34 in Die Vielfalt und Einheit der Moderne: 25 Kultur- und Strukturvergleichende Analysen, edited by Thomas Schwinn. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag. Schwinn, Thomas. 2006b. “Konvergenz, Divergenz oder Hybridisierung?: Voraussetzungen und Erscheinungsformen von Weltkultur.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 58: 201-232. Schwinn, Thomas. 2007. Soziale Ungleichheit. Bielefeld: Transcript. Stichweh, Rudolf. 2000. Die Weltgesellschaft: Soziologische Analysen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Stichweh, Rudolf. 2005. Inklusion und Exklusion: Studien zur Gesellschaftstheorie. Bielefeld: Transcript. Streeck, Wolfgang. 1998. “Einleitung: Internationale Wirtschaft, nationale Demokratie?” Pp. 11-46 in Internationale Wirtschaft, nationale Demokratie, edited by Wolfgang Streeck. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus. Streeck, Wolfgang. 2001. “Introduction: Explorations into the Origins of Nonliberal Capitalism in Germany and Japan.” Pp. 1-39 in The Origins of Nonliberal Capitalism. Germany and Japan in Comparison, edited by Wolfgang Streeck and Kozo Yamamura. Ithaka, London: Cornell University Press. Vobruba, Georg. 2000. “Das Globalisierungsdilemma. Analyse und Lösungsmöglichkeiten.” Pp. 173-188 in Staatsbürgerschaft: Soziale Differenzierung und politische Inklusion, edited by Klaus Holz. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag. Weber, Max. 1980. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. 5th edition. Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck). Weiß, Anja. 2002. “Raumrelationen als zentraler Aspekt weltweiter Ungleichheiten.” Mittelweg 36: 76-91. 26