LIBERTY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW

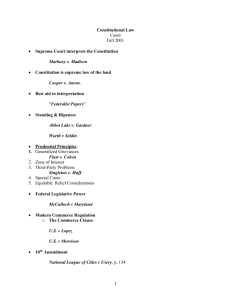

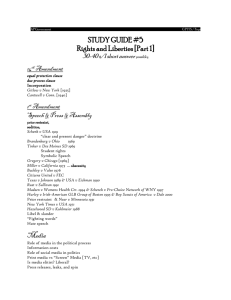

advertisement