Quality of life among children aged 2

advertisement

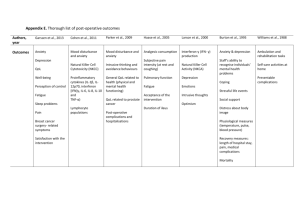

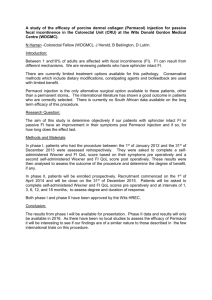

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH 2001; 11: 437-445 Q U A L I T Y O F L I F E Quality of life among children aged 2-17 years in the five Nordic countries Comparison between 1984 and 1996 LEENIT. BERNTSSON, LENNART KOHLER * Keywords: children, comparative study, follow-up, Nordic countries, quality of life e concept of quality of life (QoL) has gained increasing importance in the evaluation of health care interventions and systems of care in comparisons of disease groups and other subgroups, and in descriptions of populations at a specific point in time or over time. Recently new definitions and applications have evolved considering and evaluating the whole existence of the human being. The literature covers a range of QoL definitions depending on the context and scientific discipline. In medicine the focus is on health related QoL, • in philosophy on 'the good life', in economic science on welfare and distribution,'1"7 in social science on objective and subjective well-being" and in psychology on psychological well-being. ' T h e definitions may also be classified into two main categories: objective and subjective. The former indicates what the good life is whereas the latter indicates the individual's own perception of it." According to WHO's cross-cultural definition of QoL, health and QoL are complementary and overlapping.12 Most of these definitions are influenced by adult perspectives. The * L.T. Berntsson', L Kohler1 1 The Nordic School of Public Health, Goteborg, Sweden Correspondence: L.T. Berntsson, RN, MSc, MPH, The Nordic School of Public Health, Box 12133, S-402 42 Goteborg, Sweden, tel +46 31 693977, fax +46 31 691777, e-mail. leem@nhv.se existing literature on QoL definitions from the child's point of view suggests that children's health and wellbeing must be seen in its full social, economic and political context. To reach such a broad goal there is need for knowledge and research from many professions and sciences. However, there are few studies of children's QoL which include the combination of physical, social, economic and personal factors. Such a broad definition of QoL was used in a Nordic comparative study by Lindstrom 4 where QoL was defined as the essence of existence of an individual, group or society as measured objectively and perceived subjectively. The overall results showed that Nordic children enjoyed a high standard of living, that they were healthy, both physically, mentally and socially, and that the differences between the countries were small. Since then an economic recession has affected the Nordic societies followed by social, political and organisational changes, such as heavily increased unemployment rates, constrained public services and reduced social benefits. It seems that families with children have suffered mostly by these cuts in social spending but little is known how their well-being has been affected.15 There are also changes in family patterns. An important feature of the Nordic family is that there are relatively few children in each family and relatively many single-parent Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Background: The aim of the study was to analyse children's quality of life (QoL) in the five Nordic countries from 1984 to 1996, a period in which major economic recessions occurred. Methods: The study design was cross-sectional based on a random sample of 3000 children in each country, aged 2 to 17 years, totalling 15,000 in 1984 and 15,000 in 1996. The data were collected by mailed questionnaires. QoL was analysed for three spheres of life: external, interpersonal, personal including both factual and perceived variables. The external sphere represented the socio-economic conditions for the child's family, the interpersonal sphere the structure and the function of the child's social networks and the personal sphere the psychological well-being of the child. Results: The total QoL for Nordic children from 1984 to 1996 increased, but there were differences in the development of QoL between the countries. The objective QoL became better, at the same time the subjective QoL worsened, except in Denmark and Iceland. The external QoL became better, whereas the interpersonal QoL was nearly unchanged but there were differences in the development between countries. The personal QoL worsened slightly except for children in Iceland. The ranking between countries changed. Danish children had the highest subjective and Norwegian children the highest objective and external QoL. Swedish children had the highest personal QoL. Children 7-12 years had the highest QoL. Girls had a tendency to higher QoL in all ages. Conclusion: Nordic children still enjoy a high standard of living in spite of economic constraints, and the prerequisites for a high QoL are fulfilled. Further research is suggested for clarifying the complex background of these results. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH VOL. 11 2001 NO. 4 families. The number of divorces has increased from 1984 in all Nordic countries. To determine whether the societal changes described above have been accompanied by a change in children's quality of life a similar study was carried out 12 years later, of the same age groups, and using the same methods. Aim The aim of this study was to: • analyse the QoL of children from 2 to 17 years in the Nordic countries and its change from 1984 to 1996, • analyse similarities and differences in the development of QoL between the Nordic countries. MODELS AND METHODS QoL model The QoL model of Lindstrom14 is developed from Naess'9 and Kajandi's models and influenced by Allardt's welfare model. QoL consists of four spheres: global, external, interpersonal and personal (table. 1). Objective (factual) conditions and perceived subjective satisfaction (expressions, attitudes, values) are included in all dimensions. Measures The questionnaires, which were translated from Swedish into the other four Nordic languages by researchers and linguists in respective countries, were tested in pilot studies in both years. A combined set of variables was used to study the QoL of children. Each variable had a defined base level (table 2), which was specified to meet the needs Table 1 A general quality of life model, life spheres and dimensions'1 Dimensions (objective/subjective) Examples 1 Macro environment 2 Human rights 3 Policies 1 Work 2 Economy Clean environment Democratic rights Culture Employment Income 3 Housing Type of housing Interpersonal 1 Family Personal 2 Intimate 3 Extended 1 Physical 2 Mental 3 Spiritual Structure and function of social relationships Spheres Global External sphere a: Lindstrom'4 Growth, development, activity, self-esteem, meaning of existence Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Questions • Has children's QoL generally changed between 1984 and 1996? • Are there differences in development of QoL in different countries? • Are there differences in QoL between the age groups 2-6 years, 7—12 years and 13—17 years? • Are there differences in QOL between girls and boys? of children in the Nordic countries.14 The same base values were used for all countries. All the QoL-indicators were represented by dichotomous variables, values one and zero. One means exceeding the base value for a child's well-being, and zero means that the child does not have tesources over the base value. The total QoL included all the spheres, 16 objective and 9 subjective measures. The external sphere represented the socio-economic status of the family and included nine variables (table 2). The dimension work included three indicators: the parents' education, profession and work satisfaction. Education was classified into four groups based on the number of years of education: i) more than 12 years, ii) 12 years, iii) 10-12 years and iv) 9 years or less. The cut-off point for high/low education was between two and three. Social class of the parents was based on the present or the last held main occupation of at least 16 hours/week. A basic distinction was made between employees and selfemployed, including fanners. The employees were first divided into white-collat and blue-collar workers and then into groups on the basis of theit skill level. Three indicators were used to represent the family's economy: nationally defined levels of disposable income classified into six groups, income distribution (income per capita) and satisfaction with economy. The cut-off point for high/low income was between the two highest groups and the others. Type of housing, space (number of rooms/family size) and own room of the child represented the housing dimension. The questions of subjective well-being had alternatives from 'not at all satisfied' to 'satisfied'. The interpersonal sphere represented the structure and function of the child's networks and included nine variables. There were three measures of the family dimension: number of siblings, the parents' available time (full-time work/part-time work) with the child and satisfaction with family life. The intimate dimension included family type (one ot two parents), household size (more than three persons) and major.negative life events of the child, such as separation or death of the parents. The extended networks included the family's support from society (professional support) and from friends/relatives, and the parents' satisfaction with their social contacts. The personal sphere represented the child's psychological well-being and included seven variables. The dimension activities included the child's own activities and activities together with the parents and the parents' satisfaction with their activities. The measutes of the child's own activities consisted of eight different items. The choice of answers for each item was never, once or more times a year (low activity level), a month, a week or a day (high activity level). Activities together with the parents consisted of six items and for each item the respondent was asked to give the frequency of the activity as above. Further, die respondents were asked about dieir satisfaction with leisure time. The child's self-esteem was measured by six indicators: dependent/independent, passive/active, lonely/not lonely, testless/calm, depressed/happy, anxious/confident. All die items were scaled from 1-7 and the cut-off point was between 5 and 6. Quality of life among children aged 2-17 years The basic mood of the child was described with prevalence of psychosomatic complaints, satisfaction in school and peer contacts. Psychosomatic complaints were measured using six items: stomach complaints, headache, sleeplessness, dizziness, backache and loss of appetite. The respondents were instructed to make a cross only if the complaints occurred every or every other week. The child's satisfaction with nursery school /school/work was scaled very well, well, not well. Peer acceptance was measured with an item about being bullied, scaled often, sometimes or seldom/never. Variable External sphere Education Profession Work satisfaction Statistical analyses QoL-scores are the sums of simple variables over specific subsets of QoL indicators. First, means of QoL-scores are counted for each sphere, for subjective and objective variables by age, country and year. Second, to compare the mean scores in groups of children and development of QoL between the years in respective countries, linear Nature Over base level Under base level Objective Objective 12 years or more White-collar worker Less than 12 years Blue-collar worker Subjective Objective Satisfied Dissatisfied Two highest income classes No Four lowest income classes Yes Satisfied Dissatisfied Block of flats Combined disposable income Poverty (income/family member) Satisfaction economy Objective Subjective Type of housing Objective Detached house Space The child has own room Objective Objective One inhabitant per room Yes More than one inhabitant per room Objective Objective At least one sibling An only child Full-time work of both parents No Interpersonal sphere Number of siblings Available time Satisfaction family Family type Household size Life events Satisfaction friends/relatives Satisfaction social support Satisfaction contacts Personal sphere Child's activity Family activity Activity satisfaction Self-esteem Psychosomatic symptoms Peer acceptance School satisfaction a: Lindstrom14 Subjective Part-time work of at least one parent Satisfied Objective Objective Cohabiting parents At least four members Objective Subjective No separation, death of the parents Satisfied Satisfied Subjective Subjective Satisfied Dissatisfied One-parent family Less than four members Separation/death of the parents Dissatisfied Dissatisfied Dissatisfied Objective High Objective Subjective High Low Low Subjective Satisfied High score Dissatisfied Low score Objective Objective No High Yes Low Subjective Satisfied Dissatisfied Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Sampling Data from two cross-sectional population surveys in the five Nordic countries were analysed. The studies were approved by the national ethics committees. The first survey was performed in 1984 and was repeated in 1996. In both studies, random samples of about 3,000 children aged 2-17 years in each country were drawn from the population registers of the respective National Bureau of Statistics. Children in institutions were excluded. A questionnaire was mailed in March 1996, and two reminders were sent. The parent who was best familiar with the child's situation was instructed to fill in the questionnaire, together with the child, if possible. EightyTable 2 Quality of life indicators and base levels0 two percent of respondents were mothers in 1984 and 81% in 1996 but in most cases questionnaires were completed by both parents together with the child. There were 10,219 completed forms in 1984 and 10,317 in 1996. The response rates varied between countries, the mean response rate was 67% in 1984 (Denmark 73%, Finland 83%, Iceland 60%, Norway 56%, Sweden 62%) and 70% in 1996 (Denmark 69%, Finland 80%, Iceland 68%, Norway 65%, Sweden 69%). The respondents by country, age and gender in 1984 and 1996 are shown in table 3. An analysis of the non-respondents was performed in both years. There were no differences between respondents and non-respondents in terms of age and sex but families with low education (2-3,5%), working class (3-5%) and one-parent families (3.5-10%) were over-represented among non-respondents in both years. Otherwise representativeness of the samples was high. EUROPEANJOURNALOFPUBLICHEALTHVOL.il 2001 NO. 4 regression analysis and descriptive statistics controlling for age and gender were used. Third, for multiple comparisons between countries, a one-way Anova post hoc multiple comparison with Tuckey's test was used.1' The results from a normal probability plot and a histogram of residuals suggested that the errors were normally distributed. The influence of random variation was assessed by means of standard errors. The statistical significance level used was 5%. For nine variables in both studies the internally missing values (from 1.5 to 10%) were substituted with the mean value for that variable in its age group: 2-6 years, 7-12 years and 13-17 years. The background variables were age, gender, country and study year. The statistical analyses were all undertaken using the software package SPSS/PC. External sphere Table 4 shows that the external QoL has increased for all children in the Nordic countries but there are differences in the development between countries. The mean scores for Norwegian, Swedish and Danish children were quite similar in 1984 and somewhat lower for Icelandic and Finnish children. In 1996 Norway had the highest value as of external conditions closely followed by Denmark. The development was less favourable for Sweden and Iceland whereas Finland is now closer to Sweden. External indicators (tables not presented here) such as the families' educational level, professional status and disposable income increased in all countries (except income in Iceland). Danish and Icelandic families were more satisfied with their work situation than 1984 whereas the other countries were more dissatisfied. Although the families' economic resources increased the families were Table 3 Respondents by country, age and gender in 1984 and 1996 1984 N Country Sweden Iceland Norway 1,934 1,577 1,856 Finland Denmark 2,705 2,219 2,034 2,169 10,291 10,317 3,600 13-17 All 3,783 2,908 3,351 3,816 3,022 10,291 10,189 Boys 5,183 Girls All 5,097 10,280 5,248 4,968 10,216 All countries Age (years) Gender 1996 N 2,130 2-6 7-12 2,048 1,936 Interpersonal sphere The interpersonal QoL was nearly unchanged for Nordic children as a whole but there were differences in the development between countries. Icelandic and Danish children had the highest score values. The greatest downward change in scores was estimated for Norway and the greatest upward change for Iceland followed by Denmark. There were more children who had no siblings and the parents had less time to spend with their children. Most children were living with two parents in both years but there were more children who had experienced major negative life events in all countries in 1996. Satisfaction with family life increased for Icelandic and Danish parents and decreased for the other countries. The societal support increased in all countries except in Norway. Families were also more satisfied with the support from relatives and friends except in Norway and Finland. Only Icelandic families were more satisfied with the support in general. Personal sphere The personal QoL scores for Nordic children were slightly lower in 1996 except for Icelandic children. Sweden ranked in first, Denmark second and Norway third place in both years. Iceland ranked fourth and Finland slightly lower. Children's own activity level and together with parents increased in the Nordic countries (except family activities in Sweden and Finland) but families were more dissatisfied with their leisure time except in Iceland. Children's self-esteem decreased in Sweden, Norway and Finland and increased in Iceland and Denmark. Despite an increase in bullying and psychosomatic complaints more children enjoyed school in 1996 except in Finland. Total, subjective and objective QoL Total QoL increased for Nordic children as a whole but there were changes in the development between countries. The highest total QoL was found in Denmark and the lowest in Finland. The greatest upward changes in scores were found in Iceland and Denmark. There was no significant change in subjective QoL for Nordic children as a whole, but, again, there were differences between countries. For Icelandic and Danish children the subjective scores increased, while they decreased for the other countries. Danish children had the highest subjective QoL. Objective QoL increased for Nordic children as a whole but there was a difference in the development between countries. Norway had the highest scores and Finland the lowest. Are there differences in QoL between the age groups 2-6 years ,7-12 years and 13-17 years? Table 5 shows that the external QoL was higher in older children, and increased significantly in all ages from 1984. The youngest age group had the lowest external score Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 RESULTS Table 4 presents the development of QoL adjusted for age and gender for each country. In table 5 the development of QoL is presented separately for the three age groups, and in table 6 for boys and girls. more dissatisfied with their economy except in Iceland and Denmark. The housing conditions were generally better in 1996 than in 1984 but there were minor differences between countries. Quality of life among children aged 2-17 years value. The interpersonal QoL was highest in the youngest age group in both years and there was a significant increase between the years in this age group. QoL in the personal sphere worsened significantly from 7 to 17 years of age. Total QoL increased in all age groups. In both years children of age 7-12 years had the highest QoL scores. There was a tendency to lower subjective QoL scores for the two older age groups in 1996. Objective QoL scores were significantly higher for all ages as they were on the external sphere. Are there differences in QoL between girb and boys? DISCUSSION The Nordic countries are known for a long history of affluence, which is reasonably well distributed in the population. The political development has favoured the creation of strong welfare states, assuring all citizens a wide social protection and an adequate standard of living. The results from the QoL study in 1984H confirmed that the majority of Nordic children had the prerequisites required to enjoy a high QoL. The Welfare States, however, were shaken in the economic recessions of the 1990s. The main objective of this new study was to examine if the social changes had affected the high level of QoL. The results show that citizens in the Nordic countries still Table 4 Mean quality of life scores by country in 1984 and 1996, adjusted for age and gender Sphere (number of variables) External (9) Interpersonal (9) Personal (7) Mean 6.02 Norway Finland Denmark 6.21 6.23 5.49 6.01 (1.96) *** 5.86 7.02 (2.17) (1.92) *** All countries 5.89 (2.04) *** Sweden (172) * Iceland Norway 6.67 6.40 7.12 (1.70) (1.62) *** Finland Denmark 6.49 6.46 (1.60) (170) All countries 6.61 (1.68) Sweden 5.30 *** Iceland Norway 4.18 (1.24) (1.36) (1.27) * (1.34) (1.30) (1.35) *** Sweden Iceland Norway Finland Denmark All countries Sweden Iceland Norway Finland Denmark All countries Objective (16) Mean ** All countries Subjective (9) (SD) (2.10) (1.88) Finland Denmark Total (25) 1996 1984 Country Sweden Iceland Sweden 5.83 4.97 4.78 *** *** *** *** *** 5.99 6.85 6.38 (SD) (2.00) (1.99) (172) (2.03) (1.77) (1.96) 6.54 6.78 (1.74) (1.72) 6.54 6.41 6.67 6.59 (1.73) 5.12 4.65 (1.34) (1.25) (1.32) 4.87 4.60 (1.67) (1.71) (1.72) (1.37) (1.35) * 5.01 4.85 (1.34) (3.44) (3.32) (3.35) *** 17.79 17.20 (3.44) (3.30) * 18.40 (3.20) (3.31) 17.47 17.30 (3.51) *** 16.87 18.46 (3.45) *** 17.74 6.18 4.75 (1.78) (1.95) *** 5.90 5.66 6.51 6.25 (1.84) (1.81) (1.89) 5.16 4 90 17.88 16.25 18.19 16.72 6.09 6.02 Iceland 11.71 11.50 Norway 11.68 (3.32) *** *** *** *** (1.94) (2.42) (2.35) (2.32) *** 6.07 5.86 (1.91) (1.78) (1.86) (1.88) 6.50 6.00 (1.90) (1.89) 11.89 (2.37) (2.35) 11.53 *** (3.36) (3.38) 12.33 11.02 Finland Denmark 10.47 11.39 (2.48) (2.42) *** *** 11.95 (2.17) (2.33) (2.28) All countries 11.28 (2.47) *** 11.74 (2.34) Statistically significant differences, * p<0 05," p < 0 0 1 , *** p<0.001 be cween years 1984 and 1996 Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 There were no significant gender difference in QoL in external and interpersonal scores (table 6). In the personal sphere girls aged 2-12 years had significantly higher QoL scores than boys in both years. Both boys and girls in the oldest age group had the lowest scores in 1996. Girls had a tendency to higher total QoL in all ages and in the middle age group significantly higher total QoL in both years. Girls in the youngest age group had the highest subjective QoL in both years. enjoy a high standard of living and that the prerequisites required for a high QoL are fulfilled, also for children. Actually, the total QoL has increased for Nordic children in general, but there are differences in the development between the countries, and their relative order has changed. The objective part of QoL also improved in all countries, but, at the same time, the subjective part worsened for all countries except for Denmark and Iceland, where it improved. In terms of total QoL Norwegians and Danes are now closer to each other than to the Icelanders and Finns, and EUR0PEANJOURNALOFPUBLICHEALTHVOL.il 2001 NO. 4 shown that subjective wellbeing and happiness are not directly related to external conditions. Americans whose income increased over a 10-year period were not happier than those whose income was stagnant. Correlation between income and well-being is important only in the poorest countries of the world and where the income inequality in society is large.24'7 Age differences in QoL were found in all spheres. This can Total (25) 2-6 7-12 13-17 2-17 Subjective (9) Objective (16) 17.04 17.81 (3.31) (3.52) *** 16.94 17.30 (3.47) (3.45) *** 17.84 18.04 17.25 *** 17.74 (3.37) (3.37) (3.39) 6.10 6.02 (1.87) (1.88) 5.87 6.00 (1.93) (1.89) 11.75 12.02 (2.37) (2.35) 4*S 11.39 *** 11.74 (2.26) (2.35) ** 2-6 6.05 (1.90) 7-12 13-17 2-17 6.07 5.92 (1.97) (1.93) 6.02 (1.94) 10.99 (2.40) *** 11.74 11.03 11.28 (2.50) (2.42) (2.46) *** 2-6 7-12 13-17 2-17 Statistically significanidifferences, • p<0.05, «p<0.01, •** p<0.001 between years 1984 and 1996 (3.38) Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 be explained by developmental, social and behavioural Swedes have a middle position. In terms of subjective QoL factors. Children in the age group 2-6 years, who have the differences between countries are quite similar in the youngest parents, had the lowest external QoL. Due 1984 and 1996 except that Iceland has approached the to the higher number of parents still studying, the proother Nordic countries. It may be surprising that the portion of low-income families has increased in the age substantial economic recession has not noticeably band 18-29 years.25 affected the QoL. It could, however, very well be that the welfare systems are so stable and protective that the The changes in the interpersonal and personal QoL inrecession did not reach the core issues as expressed in the dicate that the child's intimate networks have worsened. QoL scores, at least not in this time span.19 UnThe parents' decreased time with children, fewer siblings, employment rates and subsides increased in all countries increased bullying and negative life events may explain except in Denmark.20-21 The study results showed a an increase in psychosomatic complaints and the lower higher educational level and professional state in self-esteem in children. These interpersonal and personal families. The disposable income and its distribution factors form the child's mental well-being. increased in all countries except in Iceland. This The interpersonal QoL was lowest in the oldest age group. might explain the higher external and objective QoL. According to a Swedish welfare study the family situation The standard deviations of the mean scores do not has changed at least three times for about 30% of children show widening socio-economic gaps, except in Iceland 13—17 years old, whereas for 10% of children 3-6 years in the external sphere. But other studies, both from old the family situation has changed once.26 The close this project and from others, confirm that there is a relation between the families' QoL and the children's widening socio-economic health gap among Nordic well-being is again clearly documented. ' The oldest children. 2 ' " The results in this study represent the children had also the lowest value of personal QoL. overall population. In a future paper disadvantaged groups Several studies report a higher prevalence of psychowill be analysed. somatic complaints and bullying among adolescents.28 Another possible explanation for the fact that the Table 5 Mean quality of life scores by age in 1984 and 1996, adjusted for age and gender economic recession did not 1996 1984 show decrease in QoL-scores Sphere (number of variables) Mean (SD) Mean Age (years) (SD) might be that people refrain *** (2.06) External (9) 2-6 6.02 5.57 (2.04) from having children until *** 7-12 5.99 (1.96) 6.38 (2.07) the economy is more stable. *** (1.79) 13-17 6.15 (1.95) 6.75 Thus, there were more *** 5.89 (1.96) 6.38 2-17 (2.04) children without siblings in 1996, and consequently * 2-6 (1.60) (1.61) 6.95 6.87 fewer individuals to share Interpersonal (9) 7-12 6.79 (1.68) 6.71 (1.63) the family income. 13-17 6.08 (1.73) 6.05 (1.74) The results also indicate that 6.62 6.59 2-17 (1.68) (1.71) the perceived part of QoL has worsened. The lack of *** 2-6 (1.25) 4.95 (1.24) 4.74 association between object- Personal (7) *** 7-12 5.01 (1.35) 5.13 (1.39) ive and subjective scores is *** (1.40) 13-17 4.80 (1.38) 4.55 not new. American re* 24 2-17 4.90 (1.35) 4.85 (1.34) searchers have in several representative samples Quality of life among children aged 2-17 years Study strengths and weaknesses It may be questioned if the QoL model used here really captures all aspects of QoL. Physical health components of the child were not included. Although it is probably safe to assume that people who have fewer symptoms, more happiness, and better functioning in daily activities have a better QoL, there is still confusion whether these concepts are components of QoL or determinants of QoL.31 It may also be questioned if social well-being and socio-economic factors should be considered as a part of QoL or predictors of QoL. Here QoL was defined as the essence of existence of the individual, which presupposes Table 6 Mean quality of life scores by age and gender in 1984 and 1996 1996 1984 Sphere (number of variables) Age (years) External (9) Total (25) Subjective (9) Objective (16) Boys (SD) Mean 2-6 7-12 5.59 5.99 (2.04) (2.10) 5.55 5.98 13-17 2-17 6.16 5.89 (1.94) (2.05) 6.15 5.88 6.90 (1.59) 6.83 (1.59) 6.74 6.06 6.59 (1.61) (1.67) (1.72) (1.69) 6.70 6.05 4.66 (1.26) 5.01 13-17 6.83 6.09 2-17 6.65 2-6 7-12 4.82 5.19 (1.23) (1.38) *** ** 13-17 2-17 4.80 4.95 (1.39) (135) *** 4.85 2-6 7-12 17.17 17.93 (3.27) (3.51) * * 16.90 13-17 2-17 16.96 17.39 (3.43) (3.43) * 2-6 6.15 (1.88) ** 7-12 13-17 6.13 5.95 (1.97) (1.92) 2-17 6.08 (193) 2-6 11.01 11.81 (2.37) (2.50) 11.01 11.30 (2.41) (2.46) 7-12 13-17 2-17 (1.74) (1.67) ** 5.06 4.81 Boys Girls Mean Interpersonal (9) 2-6 7-12 Personal (7) G iris (SD) (2.05) Mean 6.05 (2.04) (197) 6.44 6.73 6.40 (2.04) (1.40) 6.96 6.59 (SD) (2.07) (1.95) (1.76) (1.95) (1.64) (166) (1.74) (1.72) (1.23) (1.33) Mean 6.01 6.32 (2.04) (198) 6.77 6.36 (1.81) (1.97) 6.87 6.71 6.05 6.58 (1.68) (1.76) (1.72) * 4.90 *** 4.89 4.53 4.78 (SD) (1.60) (1.24) (1.36) (1.39) (1.37) (1.36) 5.14 4.57 4.93 (1.39) (1.34) *** (3.34) (3.52) 17.93 18.23 (3.41) (3.40) 17.76 (3.36) ** 17.85 (3.38) (3.51) 17.24 (3.48) 17.84 (3.34) (3.39) ** 17.27 17.65 (3.39) (3.38) 5.94 6.01 (1.92) 6.15 5.88 5.95 (1.95) 6.07 5.95 6.04 5.98 (1.86) (1.96) (1.94) 6.06 (1.87) 10.97 11.68 11.05 (2.41) (2.49) 11.78 (2.38) 11.26 (2.47) 12.16 11.56 11.78 (2.34) (2.36) (2.36) 17.70 16.93 17.21 (2.43) Statistically significant differences, * p<0.05, **p<0.01,*** p<0 001 between girls and boys in 1984 and 1996 (1.88) (1.86) (1.89) * ** 5.80 5.95 11.72 (134) (1.89) (196) (1.90) *** 11.88 (2.34) (2.37) * 11.47 11.70 (2.24) (2.32) Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 necessary internal and external resources for a good life.14 Every child has a personal sphere that is experienced in a context of social relationship and support. This in turn has a socio-economic context and beyond this a macro level (society). One of the key variables for changes in the interpersonal sphere was the families' satisfaction with the social support, which might be dependent on the family policy in respective countries. The QoL instrument used here is a generic one, which refers to a general approach available to all types of people regardless of their condition or situation. The concept is attuned to the WHO definition of QoL12 and its questionnaire for adults that includes six domains: physical, psychological, level of independence, social relationships, environment and spirituality. There are few QoL instruments for children that have been tested and validated in a large population study like this. It is designed specifically for children in the Nordic countries. The instrument has been recommended for its broad aspects in two recent overview articles of children's QoL.33'34 Pal's review33 revealed that most QoL instruments use a simple concept of health. Only five instruments included broader definitions. The least favourable personal QoL was seen in children aged 7-17 years. Gender differences on the personal sphere may be explained by social and behavioural factors. School dissatisfaction and bullying are more prevalent among boys than girls.28 Boys in puberty are more extrovert and behave more aggressively29 whereas girls are more introvert. A Finnish follow-up study concludes that boys have more health problems than girls, caused by social factors and school problems.30 EUROPEANJOURNALOFPUBLICHEALTHVOL.il 2001 NO. 4 Another problem in the present study is children and parents as respondents. But it was necessary to get the parents' view of the child in the family and the society context according to the model. This may bias the results, especially for differences between age groups and over time. In a Dutch study of health-related QoL research35 the children reported a significantly lower health-related QoL than their parents on the physical complaints, motor functioning and positive emotion scales. The parent report might provide a substitute for children's healthrelated QoL at a group level, but large differences can exist in proxy agreement at the individual child-parent level. In the present study the self-esteem of the child and symptoms may be underestimated if the child alone has filled in the questionnaire. Another aspect that might influence the results is the respondent's gender. In the WHO study32 significant gender differences were found in physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains. In this study social support, economy and mental and spiritual dimensions might be overestimated but the proportion of the mothers as respondents was the same (about 82%) in both years. In future studies information should be collected using a separate questionnaire for older children and parents. Finally, many of the significant differences between years, countries and groups of children may seem to be trivially small in terms of their contribution to the variation of QoL. However, even small changes in a negative direction might be a warning sign to observe and follow up what is happening in society. CONCLUSIONS The total QoL for Nordic children is very high, and increased from 1984 to 1996, although there were differences in the development of QoL between countries. The objective QoL for children became better in all countries, at the same time the subjective QoL • I worsened, except in Denmark and Iceland. The external QoL became better, whereas the interpersonal QoL was nearly unchanged for Nordic children as a whole but there were differences in the development between countries. The personal QoL worsened slightly except for children in Iceland. The ranking between countries changed. Danish children had the highest subjective and Norwegian children the highest objective and external QoL. Swedish children had the highest personal QoL. Children of age 7-12 years had the highest QoL. Girls had a tendency to higher QoL in all ages. It may be concluded that QoL for children is reflected by the societal context with its external, interpersonal and personal resources. Further research using other variables is needed to clarify the complex background of these results. Based on these quantitative findings, a new indepth study of QoL of children will be performed later, using qualitative methodology. We are grateful for research support from the Joint Committee of the Nordic Social Science Research Councils. 1 Sullivan M. Quality of life assessment in medicine Nord J Psychiatry 1992,46:79-83. 2 Wiklund I, Lindvall K, Swedberg K. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials. Acta Med Scand 1986;220:1-3. 3 Nordenfeldt L. Livskvalitet och halsa, teori och kritik (Quality of Life and health, theory and critique). Falkoping: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1991. 4 Morris MD. Measuring the condition of the World's Poor: the physical Quality of Life Index. New York: Pergamon Press, 1979 5 Jordan TE. Developing an international index of quality of life for children: the NICQL Index. J R Soc Health 1983,4:127-30. 6 Jordan TE. Estimating the quality of life for children around the world: Nicol 92. Soc Indicators Res 1993;30:17-38. 7 Ceresto S, Waitzkin H. Economic development, Political-Economic system, and the Physical quality of life. J Public Health Policy 1988;9(1):104-20. 8 Allardt E. Art ha att alska att vara (To have, to love, to be). Lund: Aldus, 1975. 9 Naess S. Psykologiska aspekter ved livskvalitet (Psychological aspects of Quality of Life). INAS arbeidsrapport; 1974:11. Oslo: Institute for Applied Social Research, 1974. 10 Kajandi M, Brattlof L, Soderlind A. Livskvalitet. Berakning av ett livskvalitetsinstruments reliabilitet (Measuring the reliability of a Quality-of-Life-instrument). Uppsala: Psykologiska Enheten, UllerSkers sjukhus, 1983. 11 Nordenfelt L. Towards a theory of happiness: a subjectivist notion of quality of life. In: Nordenfeldt L, editor. Concept and measurement of quality of life in health care. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic publisher, 1994. 12 The WHOQOL Group, 1994. Quality of life assessment: what quality of life? In: World Health Forum. Geneva: WHO, 1996. 13 Kohler L. Child public health: a new basis for child health workers. Eur J Public Health 1998;8:253-5. 14 Lindstrom B. Quality of life: a model for evaluating health for All. Conceptual considerations and policy implications. Soz praventivmed 1992;37:301-6. 15 Socialstyrelsen. Barns villkor i forandringstider (Children's living conditions in a time of change). Report No. 1994:4. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare, 1994. 16 Nordic Statistical secretariat. Yearbook of Nordic statistics 1995. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 1995. 17 Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LJ, Muller KE. Applied regression analysis and other mutivariable methods. Boston, MA: PWS-Kent PubICo, 1988. 18 Kohler L. Children with and without disabilities in the Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Our first study was carried out already in 1984- It may be that the people have other values for their lives to day. Nevertheless, the standard deviations of QoL scores do not differ significantly over years. In a future study the QoL of children with long-term illness will be studied. In another study socio-economic conditions will be treated as an external factor for interpersonal and personal QoL. Although mailed questionnaires have certain limitations in revealing complex and sometimes sensitive conditions of family life it was the only possible method in such a large sample. Questionnaires may also have problems of non-respondent, interpretations of text and translations of questionnaires in comparative studies. The translations were performed both by the specialist in child health and linguists, which should minimise errors. The nonrespondent rate was higher among one-parent families in both studies and in all countries. It may influence the results in the interpersonal sphere. The study design was cross-sectional which limits the analysis to the two points, 1984 and 1996. A longitudinal study could highlight development of QoL better. Quality of life among children aged 2-17 years 27 Thinger-Thalman M. Quality of life of single parent families: disparate voices or a long overdue chorus. Marriage S Family Review: a bimonthly periodical. New York: The Haworth Press 1995;20(3-4):513-32. 28 King A, Wold B, Tudor-Smith C, Harel H. The health of youth: a cross-national survey. Copenhagen: WHO Publications European services, 1996. 29 Goodyer IM. Risk and resilience process in childhood and adolescence. In: Lindstrdm B, Spencer N, editors. Social paediatrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. 30 Gissler M, Jarvelin M-R, Louhiala P, Hemminki E. Boys have more health problems in childhood than girls: follow-up of the 1987 Finnish birth cohort. Acta Paeediatr 1999,88:310-4. 31 Stewart A. Conceptual and Methodologic Issues in Defining Quality of Life: State of Art. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing 1992;7(1)3-10. 32 The WHOQOL GROUP. The world health organisation quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998;46(12): 1569-85. 33 Pal KD. Quality of life assessment in children: a review of conceptual and methodological issues in multidimensional health status measures. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996,50:391-6. 34 Raphael D. Determinants of health of North-American adolescents: evolving definitions, recent findings, and proposed research agenda. J Adolesc Health 1996; 19:6-16. 35 Theunissen NCM, Vogels TGC, Koopman HM, et al. The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health related quality of life research. Qual Life Res 1998,7:387-97. Received J November 1999, accepted 8 June 2000 Downloaded from http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on March 6, 2016 Nordic countries, a Nordic project. Scand J Soc Med 1993;21(3):146-9. 19 Christoffersen MN. A follow-up study of long term effects of unemployment in children: loss of self-esteem and self-destructive behavior among adolescents. Childhood 1994;4:212-20. 20 NOSOSKO. Nordisk Socialstatistisk Komite. Social trygghed i de nordiske lande 1987: omfang, udgifter og finansiering (Social security in the Nordic countries in 1987: extent, expenditure and financing). Copenhagen: Nordic Statistical Secretariat, 1989. 21 NOSOSKO. Nordisk Socialstatistisk Komite. Social trygghed i de nordiske lande 1996: omfang, udgifter og finansiering (Social security in the Nordic countries in 1996: extent, expenditure and financing). Copenhagen: Nordic Statistical Secretariat, 1998. 22 Bremberg S. Battre halsa for barn och ungdom (Better health for children and young people). StockholmFolkhalsoinstitutet, 1998. 23 Halldorsson M, Cavelaars A, Kunst A, Mackenbach J. Socio-economic inequalities in health and well-being of children and adolescents in Iceland. Scand J Public Health 1999,27:43-7. 24 Myers DG, Diener E. The pursuit of happiness: new research uncovers some anti-intuitive insights into how many people are happy and why. Scientific American 1996;274(5):70-3 25 Nordiska ministerradet. Den nordiska fattigdomens utveckling och struktur (The development and structure of poverty in the Nordic countries). Tema Nord 1996:583. Copenhagen. Nordic Council of Ministers, 1996. 26 Statistics Sweden. Barn och deras familjer 1992-1993. Rapport 89. Levnadsforhallanden (Children and their families 1992-1993: living conditions). Orebro: Statistics Sweden, 1995.