Promoting Parent Involvement in Teen Driving

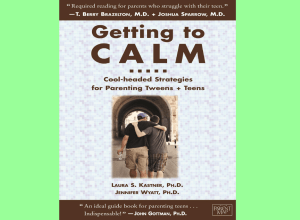

advertisement