Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

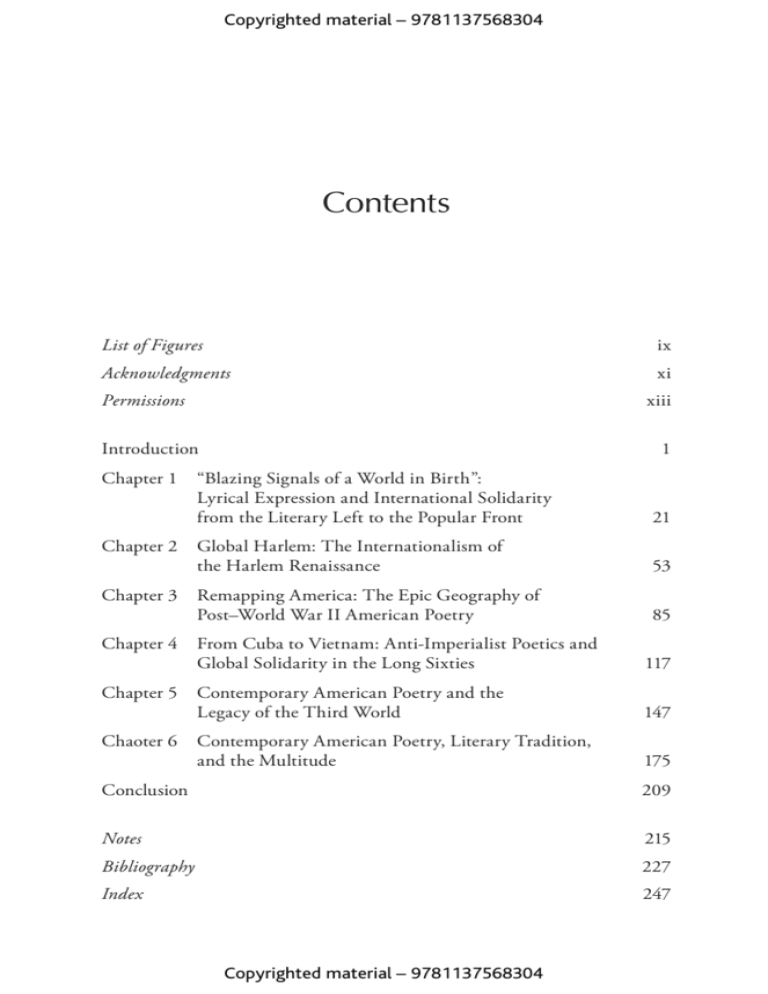

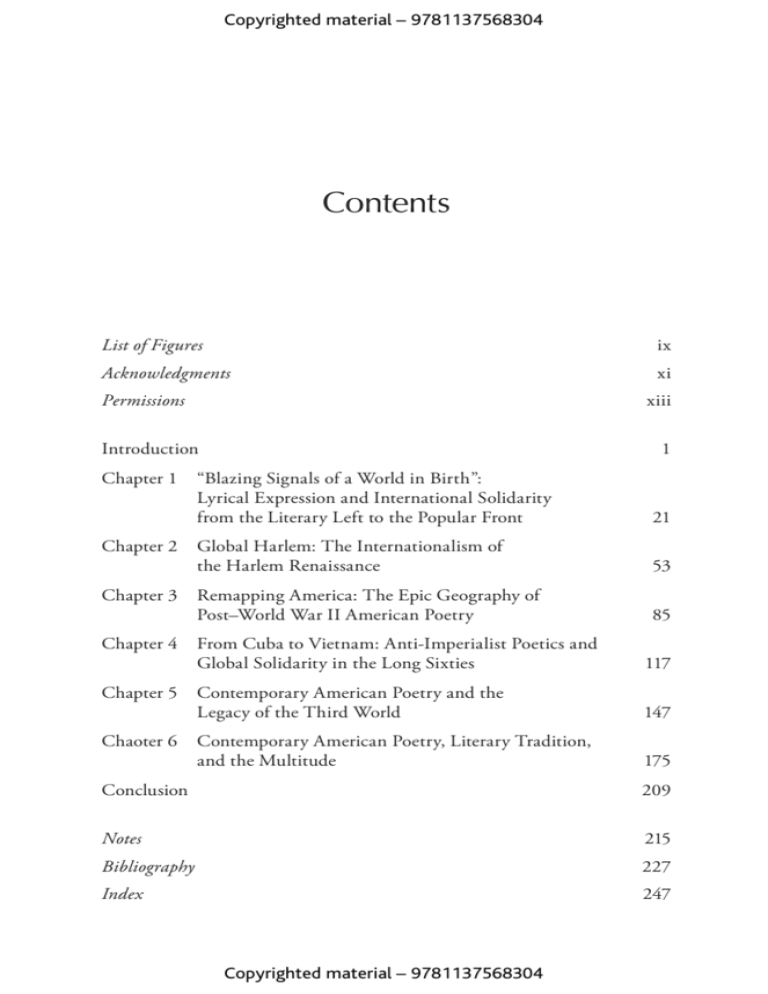

Contents

List of Figures

ix

Acknowledgments

xi

Permissions

xiii

Introduction

1

Chapter 1 “Blazing Signals of a World in Birth”:

Lyrical Expression and International Solidarity

from the Literary Left to the Popular Front

21

Chapter 2 Global Harlem: The Internationalism of

the Harlem Renaissance

53

Chapter 3 Remapping America: The Epic Geography of

Post–World War II American Poetry

85

Chapter 4 From Cuba to Vietnam: Anti-Imperialist Poetics and

Global Solidarity in the Long Sixties

117

Chapter 5 Contemporary American Poetry and the

Legacy of the Third World

147

Chaoter 6

Contemporary American Poetry, Literary Tradition,

and the Multitude

175

Conclusion

209

Notes

215

Bibliography

227

Index

247

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

A POETICS OF GLOBAL SOLIDARITY

Copyright © Clemens Spahr 2015

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication

may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication

may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission. In

accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act

1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by

the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London

EC1N 8TS.

Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

First published 2015 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

The author has asserted their right to be identified as the author of this

work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited,

registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke,

Hampshire, RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of Nature America, Inc., One

New York Plaza, Suite 4500, New York, NY 10004-1562.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies

and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Hardback ISBN: 978–1–137–56830–4

E-PUB ISBN: 978–1–137–56832–8

E-PDF ISBN: 978–1–137–56831–1

DOI: 10.1057/9781137568311

Distribution in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world is by Palgrave

Macmillan®, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England,

company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the

Library of Congress.

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

O

n his 2008 album The 3rd World (2008), rap lyricist Immortal

Technique creates a poetics of solidarity that responds to the conditions of global capitalism. The album’s lyrics are inspired by the

rhetoric of Third World liberation movements. “That’s What It Is” is full of

a seemingly hyperbolic, messianic rhetoric of rebellion and revolution: “The

resurrection,/ ripping a ball through the record section/ Flight connection/

to the Chechen border for guerrilla lessons.” This poetics of rebellion, however, receives its full meaning only in the context of the song’s concluding

sample, a dialogue snippet from the neo-noir film Deep Cover (1992). The

song samples the film’s climactic scene in which David Jason, an American

lawyer and drug dealer, advertises what he considers a promising new drug

that will prove profitable since it knows “no international borders.” When

Hector Guzman, a corrupt South American diplomat, responds that the

global production of the synthetic drug comes at the cost of South and

Central America’s profit from the drug trade (“You racist Americans. You

just want to cut us poor Hispanics completely out of the market”), Jason

retorts that Guzman misses the point: “I think you know that there’s no

such thing as an American anymore. No Hispanics, no Japanese, no blacks,

no whites, no nothing. It’s just rich people and poor people.”

While the song makes abundantly clear that racism remains a dominant

factor in a globalized world, it uses the sample to dramatize the endless

accumulation of capital as the organizing principle of global capitalism,

a principle that affects everything from the black market through politics to everyday life. But Immortal Technique deliberately omits a crucial

line from the scene in which Guzman subscribes to a class-based collectivity: “The three of us are all rich, so we’re on the same side” (Deep Cover).

Instead of presenting this class consciousness of the ruling class, “That’s

What It Is” fades into the next song, “Golpe De Estado,” which proclaims

the need for a global movement that can stand up to Guzman’s vision of a

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

2

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

global plutocracy: “Porque no podemos llamar esto un movimiento si toda

la propiedad/ intelectual pertenece a los que nos oprimen” (“Because this

can’t be called a movement if all the intellectual property is owned by those

who oppress us”; “Golpe De Estado” The 3rd World ). As the lines make

clear, before a social movement inspired by a vision of global solidarity can

emerge, education and history need to be reappropriated. Poetic expression

joins in this project: the poetics of resistance raises an awareness that such

alternatives to the neoliberal consensus and the rule of the market are necessary, possible, and have been an objective tendency, both historically and in

the present. Poetry’s cultural work, then, consists in mapping ideologies that

sustain global capitalism, while at the same time establishing a poetic space

for the imagination of a global solidarity. Read in this context, Immortal

Technique’s fierce rhetoric emerges as a poetic strategy to engage the audience in the complex project of imagining such a subject position from the

contradictions of global capitalism.

This poetics of global solidarity is characteristic of a large variety of contemporary American poetry and song lyrics. In Coal Mountain Elementary

(2009) Mark Nowak establishes a global working-class subjectivity through

his documentary poetics that juxtaposes newspaper articles, eyewitness

accounts, and lesson plans created by neoliberal think tanks, without a single line written by Nowak himself. But if contemporary poets and lyricists

(Nowak has compared his work to the sampling of a DJ, just as there is

much to be gained from analyzing song lyrics for their poetics) tackle the

conditions of globalization, their poetry also stands in the long tradition of

an engaged poetics that is connected to political activism. A Poetics of Global

Solidarity traces the transformations of this engaged poetics in modern and

contemporary American poetry and its imagination of a collective subject

position rooted in global solidarity. The book begins in the era of the great

historical upheavals in the first decades of the twentieth century when these

poets were part of an internationalist movement against imperialism and

colonialism. Later in the century their poetic imagination responded to the

threat of totalitarianism. This engaged poetry lost its public visibility in the

post–World War II years, only to regain it with a vengeance in the context

of the social movements of the 1960s. Now contemporary American poetry

engages the conditions of a globalized world increasingly characterized by

the loss of a center and clearly identifiable political antagonisms.

The trajectory of this book is provided precisely by the social and political movements with which the various poets and lyricists have affiliated

themselves. The presence or absence of these movements and their corresponding power or impotence crucially shapes the imagination of a poetic

tradition that sees poetry as a form of cultural practice potentially sparking

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

3

political activism. I establish the literary left of the 1910s and the 1930s, the

Harlem Renaissance, the political poetry of the long Sixties, post–Third

World poetry, and the poetry emerging in the context of the antiglobalization movement as part of a tradition rather than as products of discrete,

self-contained historical or literary eras. Similarly, instead of compartmentalizing modern and contemporary American poetry into a number

of poetries (African American poetry, Chicana/o poetry, women’s poetry,

political poetry, etc.), I argue that many of the poets to whom these labels

are attached in fact see themselves as part of a broad coalition of engaged

poets. Reading the vision of global solidarity that underlies large parts of

modern and contemporary American poetry along the trajectory of the rise

and fall of important social and political movements allows us to establish a

littérature engagée within the field of American poetry.

In connecting American poetry to the various social and political movements of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, this book links up with

a wave of revisionist studies in the wake of Cary Nelson’s groundbreaking

Repression and Recovery (1989). Nelson has shown that modern American

poetry was not a monolithic whole built around the canonic figures of

Pound and Eliot, but a diverse field, much of which was involved in a

vibrant cultural and political scene. Moreover, he has pointed out the social

function of modern American poetry by demonstrating, for instance, how

poem cards were circulated during rallies and at other political occasions.1

Other studies have shown how modernism intersected with the Popular

Front’s cultural institutions and politics (cf. Denning, Cultural Front; Alan

Filreis Modernism from Left to Right), how it was shaped by questions of race

and gender rather than being a self-contained avant-garde (cf. DuPlessis,

Genders), and how the Harlem Renaissance was characterized by the same

experimental impulse we associate with modernist literature (cf. Hutchinson,

The Harlem Renaissance). In a similar manner, critics have demonstrated that

the various literary movements of modernist American poetry interacted, as

in the case of the Harlem Renaissance, with working-class movements on

both institutional and political levels (cf. Maxwell, New Negro, Old Left).

These contextual approaches have sparked a renewed interest in poetry’s

social function. Such an interest is also evident in studies of the poetry of the

1960s and contemporary political poetry.2 All of these studies have revised

the canon of American poetry, charted alternative traditions, or reassessed

the field through a cultural studies lens, emphasizing the interrelationship

of form, ideology, and poetry’s social function.

If these studies are often concerned with individual authors, eras, or literary movements, I chart the poems discussed in this book as part of what

I call the engaged tradition of American poetry. This tradition cuts across

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

4

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

the various literary, cultural, and social movements of the twentieth and

twenty-first centuries. This is not to say that I simply amalgamate individual

poets into the historical narrative of a poetry that criticizes or rejects global

capitalism. The specificities of particular poetic forms, of literary eras and

traditions, as well as the ideologies of the movements figure as a significant

part of my argument. When I move across various movements and periods,

then, I try to demonstrate how these engaged poets have used a wide array of

poetic forms and rhetoric to contest the hegemonic imaginaries that maintain what Immanuel Wallerstein has conceptualized as the modern worldsystem. As a capitalist world-economy founded on the division of labor, this

“spatial/temporal zone which cuts across many political and cultural units”

(World-Systems Analysis 17) creates global capital flows and commodity

exchange, giving “priority to the endless accumulation of capital” (WorldSystems Analysis 24). World-systems analysis stresses that this system operates on multiple levels. The system’s institutions—“states and the interstate

system, productive firms, households, classes, identity groups of all sorts”—

allow the modern world-system to function properly, but at the same time

stimulate “both the conflicts and the contradictions which permeate the

system” (x).3 The authors discussed here reveal these conflicts and contradictions and contest the principles and rules on which the modern worldsystem’s multiple mechanisms of exclusion, hierarchy, and competition are

based. Their poetics of global solidarity gives rise to a subjectivity that is

consciously pitted against the liberal and neoliberal ideas maintaining the

system’s principle of endless accumulation.

In its interest in a global poetic subjectivity, this book dovetails with

recent studies that have stressed the transnational or global dimension of

American poetry. In A Transnational Poetics (2009) Jahan Ramazani has

identified textual strategies that envision “dialogic alternatives to monologic

models that represent the artifact as synecdoche for a local or national culture imperiled by global standardization, a monolithic orientalist epistemology closed to alterities within and without, or a self-contained civilizational

unit in perpetual conflict with others” (Transnational Poetics 12).4 The poets

that I discuss in the following chapters are American or have, at least, spent

the majority of their lives in the United States. While they have been firmly

embedded in local literary scenes, have been part of local and national cultural institutions, and have addressed national politics, their literary cosmopolitanism and their involvement in or support of global cultural and social

movements make them thoroughly international figures.

There is no naïve celebration of globalization, internationalism, or transnationalism in this attempt to understand world history and global politics as the partially disastrous and partially progressive results of human

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

5

interaction in given socioeconomic structures. In those moments when

change seemed a realistic possibility, as in the 1930s when social and political movements were publically visible and politically effective, poets such as

Edwin Rolfe could, even in a time of crisis such as the Great Depression,

see “blazing signals of a world in birth” (Rolfe, Collected Poems 71). Mark

Nowak, in contrast, confronted with the absence of influential global social

movements at the beginning of the twenty-first century sees it as incumbent

upon the poet “to create local and global spaces for the collective, the ‘we,’

to exist” because poetry needs to re-create the “first-person plural” that has

almost ceased to be (“Interview,” 462–63). Rolfe and Nowak write in two

different historical periods. Yet for both the creation of a poetics of global

solidarity means creating an alternative vision of the world from the contradictions of global capitalism. Thus, and logically, for the Marxist Rolfe

the new world emerges only after a symbolic journey through the “black

world underground” (Collected Poems 70), just as Nowak primarily uses citations from mainstream newspapers to represent the oppressive black world

of mining from which a sense of solidarity can potentially emerge.

A Poetics of Global Solidarity identifies a poetic tradition that articulates

collective subject positions as alternatives to the hegemonic assumptions that

maintain the exclusionary mechanisms of the world-system. To be clear:

these subjectivities do not simply pose as alternatives to, or try to resolve the

tensions and contradictions of, global capitalism. They work on the level of

representation to question the ideological mechanisms that maintain that

very system by reproducing its structures (consciously or unconsciously) in

everyday life. These subjectivities therefore remain heteronomous. While

enabling a form of social practice and political activism from a consciousness

rooted in a vision of global solidarity, they remain determined by the very

system they criticize. The poets of the 1910s and the 1930s do not simply

present a full-fledged class consciousness that needs to be adopted, but rather

develop a lyrical subjectivity that refers the reader back to the economic contradictions in which he or she inevitably is involved and which need to be

changed before such a subjectivity can become lived reality. Likewise, the

antiwar poetry of the Vietnam era declares its solidarity with the victims of

war; but the global poetic subjectivity it imagines must remain incomplete

as long as the suffering continues. All of the writers I analyze create a vision

of global solidarity that ultimately refers the reader back to the economic

structures that enable the exclusionary mechanisms of the modern worldsystem. For this reason, the global poetic subjectivity developed in these

poems and lyrics is preliminary and demands its realization outside poetry.

Despite its broad perspective, A Poetics of Global Solidarity should not

be misconstrued as an exhaustive history of engaged or political poetry. It

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

6

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

seeks instead to highlight episodes in the history of the engaged tradition

of American poetry. The poets and lyricists have been selected because of

their shared attachment to a particular form of political activism at a specific historical moment. This connects in a number of ways with Michael

Davidson’s On the Outskirts of Form, which investigates “how poems imagine a Subject constructed not as the caryatid supporting national identity

but as a more flexible entity occupying multiple geopolitical sites” (9). All of

the poets discussed here try to create a global poetic subjectivity rooted in

what Jean-Luc Nancy has called a “desire to discover or rediscover a place

of community at once beyond social divisions and beyond subordination

to technopolitical dominion” (The Inoperative Community 1). The global

and social political movements with which these poets affiliate themselves

are, in Wallerstein’s words, “all antisystemic in one simple sense: They were

struggling against the established power structures in an effort to bring into

existence a more democratic, more egalitarian historical system than the

existing one” (“Antiystemic Movements,” 160). What these poets share is

a concern to imagine a global subject position in the context of particular

social, political, and literary movements, and to create a poetics that engages

their readers in that effort.

Commitment

My selection criterion is the pedagogical dimension of poetry as it constitutes itself in the various alliances between poetry and antisystemic social

movements. The poets discussed in this book write in the context of social

movements to whose ideology they often complexly subscribe. But their

poetry does not simply teach or present a particular doctrine or politics; it

engages the reader in the mapping of a subjectivity founded on a sense of

global solidarity. Although for Jean-Paul Sartre poetry was a self-enclosed

“microcosm” opposed to the “utilitarianism” of prose (What is Literature?

32, 34), the poets discussed here are invested precisely in what he saw as

constitutive of a littérature engage: “the writer has chosen to reveal the world

and particularly to reveal man to other men so that the latter may assume

full responsibility before the object which has been thus laid bare” (38).

This object is the world-system in its various forms and with its social and

cultural consequences.

In a similar manner, Fredric Jameson has spoken of this literary operation as “cognitive mapping”: a spatial representation that enables individuals

to map their subject position within a “global social totality” (Geopolitical

Aesthetic 31). Jameson’s model adds a historical dimension to Sartre’s concepts through its incorporation of world-systems analysis. Importantly, for

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

7

Jameson it is art that can achieve such a cognitive mapping, or at least provide its outlines: “Achieved cognitive mapping will be a matter of form”

(“Cognitive Mapping” 356). The engaged tradition of American poetry

develops a dimension of art that Jameson sees as unduly neglected in critical discourse: it “foregrounds the cognitive and pedagogical dimensions of

political art and culture” (Postmodernism 50) so that the reader, in Sartre’s

words, assumes full responsibility before the modern world-system that governs his or her everyday experience.5

Understanding how this poetry tackles the ideological mechanisms that

sustain the modern world-system is particularly thought-provoking. Large

parts of modern and contemporary American poetry have tried to imagine

global poetic subjectivities beyond what Wallerstein has called the “geoculture” of liberalism—a liberal universalism that “proclaimed the inclusion of

all as the definition of the good society” (World-Systems Analysis 60), while

at the same time excluding a considerable part of the world population from

access to socioeconomic resources, whether through hierarchical gender

relations, through a form of structural racism, or through economic deprivation. For Wallerstein “geoculture” does not refer to a supposedly unified

or globalized culture (there are always multiple cultural traditions) but to the

hegemonic imagination that maintains and reproduces the structures of the

modern world-system.

The poets and lyricists discussed in this book can best be understood

in terms of Adrienne Rich’s description of Karl Marx as the “great geographer of the human condition” who revealed “how profit-driven economic

relations filter into zones of thought and feeling” (“Credo of a Passionate

Skeptic”). In a similar manner, contemporary poet Anne Waldman has

described the task of her epic poem Iovis as the “delineation of map of

starvation” (Iovis Trilogy 671) and the creation of “a radical celestial mappemunde, wanting to shift the discourse toward another shore . . . anteriorward ”

(946).6 This claim can be transferred to all of the poets and lyricists discussed in this book: they map the conditions of the modern world-system

and show how these affect and frequently inhibit the imagination. Their

poetry fractures the supposed ideological coherence of nations and communities to reveal the fundamental class conflict as well as the race and

gender inequalities at the bottom of these societies. At the same time that

they criticize an often unconscious commitment to the re-creation of the

status quo, these poets seek to engage and transform these ideologies in

the name of an egalitarian reorganization of the world. They reveal, in

Sartre’s words, that commitment is constitutive of our existence: “Most

men pass their time in hiding their commitment from themselves” (What

is Literature? 76).

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

8

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

While the poems reveal the world-system’s false universalism, they do

not simply develop a “truly” universal, global subjectivity. The subjectivity

that comes into being is not simply shown; it is produced in these poems.

In his Notebooks for an Ethics, Sartre demands: “Replace the pseudoobjectivity ‘human beings’ by a veritable collective subjectivity. Assume the

detotalized totality. We make up one yet we are not unifiable” (15). When

I speak of a global poetic subjecticity, it is more than the existing ideology

of a movement or an agreed-upon truth; it is a collective subjectivity that

constitutes itself poetically in opposition to the dominant geoculture. The

global poetic subjectivities of modern and contemporary American poetry

do not erase individual desire or identity, but rather come to constitute the

horizon of the individual’s relationship with the world. Individual consciousness is not simply replaced by a collective subjectivity, transposed, for

instance, into a proletarian collectivity, a black nationalist consciousness, or

merged into a transcendent notion of “the Other.” Instead, the individual

becomes a subject who understands him- or herself as someone constantly

positioning him- or herself in relation to the socioeconomic conditions of

the world-system.

Langston Hughes’s “Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria” (1931), for

instance, offers a trenchant critique of the luxury hotel’s supposed function

as a space of culture and cultivation. The poem reveals the Waldorf-Astoria

to be the latest manifestation of a long history of class conflict and exploitation, with the speaker finally calling out: “Mary, Mother of God, wrap

your new born babe in the red flag of Revolution” (Collected Poems 146).

Hughes connects a local site (the Waldorf-Astoria) to a secularized providential history: the Soviet Union realizes the promise of Christianity and

solves the contradictions epitomized by the Waldorf Astoria. This rebirth

is achieved as the speaker reveals the logic of magazine headlines that celebrate the Waldorf-Astoria while they simultaneously ignore its participation in socioeconomic processes of exclusion. Vanity Fair ’s advertisement

of the Waldorf-Astoria as featuring “All the luxuries of private home . . . ”

is juxtaposed with the speaker’s ironic comment that for this reason the

poor and hungry should “choose the Waldorf as a background for your

rags” (142). As a result of Hughes’s collage, the individual (the “new born

babe”) emerges as part of a collective subjectivity created through New

York City’s class and race geography (“GUMBO CREOLE” is served but

ethnic groups are excluded 144). Instead of showing a subject in rebellion,

Hughes’s poem stages the systemic contradictions to which a global poetic

subjectivity must respond.

In “These Men Are Revolution,” another poem from the Depression

era published in the New Masses in 1934, Edwin Rolfe similarly absorbs

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

9

and transforms the socioeconomic hardships of the Great Depression into a

poetic imagery that stresses the people’s potential agency:

These men are revolution, who move

in spreading hosts across the globe

(this part of which is America), who love

fellow men, earth children, labor

of hands, and lands fragrant under sun

and rain, and fruit of man’s machinery.

(Collected Poems 79)

America here is literally bracketed. It is the local manifestation of a global

constellation. Rolfe rewrites the subject through the conditions of global

capitalism, but from a perspective of solidarity that highlights the necessity to overcome the lines on the map that mark both possession and

nationhood: “Soon there will be no line on any map/ nor color to mark

possession, mean ‘Mine, stay off ’” (80). Like Hughes, Rolfe does not simply celebrate the proletariat, but rather sees its (unwilling) complicity in

reproducing structures of exploitation: “your hands dug coal, drilled stone,

sewed garments, poured steel to let other people draw dividends and live

easy” (144). At the same time, the poem displays a faith in the men who

will live the revolution. Poetry imagines a global solidarity beyond imperialist color-coded maps and beyond maps that are built on “mines”—both

in the sense of coal mines and the possessive ideologies of accumulation

underlying them.

Both Hughes and Rolfe assert that global capitalism not only structures

everyday life and the geography of human affairs, but also that individual social practices constantly re-create and reinforce this system. Global

capitalism relies on individuals’ (conscious or unconscious) commitment

to its permanent reproduction. As Wallerstein has argued, this permanent

re-creation is precisely what renders these systems historical phenomena

and thus subject to change: “The historical systems within which we live

are indeed systemic, but they are historical as well. They remain the same

over time yet are never the same from one minute to the next” (Wallerstein,

World-Systems Analysis 22). Because of its reliance on social practice, such a

system can be tackled and changed through political and social resistance,

but it can also be changed through vicissitudes in cultural relations or the

redefinition of the domestic sphere, in short, through the imagination of

alternative subjectivities. The poems discussed in this book identify such

sites of complicity as potential sites of resistance, from world politics to the

unit of the household. They prompt us, as readers, to accept our inevitable

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

10

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

positioning in the world-system and urge us to commit ourselves to imagining a future that is significantly different from the present.

Poetic Communities

If global capitalism in its various manifestations is the constant reference

frame for this engaged poetry, the institutional, cultural, and socioeconomic

formations that configure the moments of the modern world-system into

microsystems change considerably. The two poets I addressed, Hughes and

Rolfe, wrote at a time when they could rely on a close alliance between

literature and an effective political activism. Both poems appeared in the

Communist New Masses which, besides being a political magazine, was an

influential site of cultural exchange with a reputation for publishing seminal

writers such as Ernest Hemingway, William Carlos Williams, and Richard

Wright. The Harlem Renaissance’s and the Popular Front’s cultural output

were closely linked to effective political institutions that, in turn, understood culture and literature to be part of their struggle for justice. For a

brief moment, during the 1960s, with various social movements seizing the

moment to change the course of world history, poetry regained something

of its public visibility; and yet, it never reestablished the close connection

to everyday life and political debates that it displayed in the early twentieth century. Anne Waldman’s map of poverty and resistance, her “radical

celestial mappemunde,” engages in the same project of poetic solidarity, but

responds to a very different socioinstitutional situation. Waldman’s epic Iovis

project (1993–2011) is presented at a time when poetry needs to reconsider

and reassert its connections to social movements and politics.

The close link between literary and social movements that existed for the

proletarian poets or the Harlem Renaissance writers, and even the visibility

that T. S. Eliot enjoyed among academic audiences as when he spoke in front

of 14,000 people in a basketball arena, simply no longer exist. Adrienne Rich

addresses the problems of contemporary activist poetry in “North American

Time” (1983). In the poem’s middle section, Rich portrays the poet’s persisting desire to be politically relevant because of her poetry. “I am thinking this

in a country,” she writes, “where poets don’t go to jail/ for being poets, but

for being/ dark-skinned, female, poor” (Later Poems 135). Instead of being

taken seriously for presenting poetic alternatives to the world as it is—a

prophetic vision that could spill over into social reality and inspire social

practice—poets are sent to prison for political and social reasons that are

disconnected from their poetic production.

But Rich’s assessment also exemplifies how the desire to link poetry

to social movements has remained a constant factor in modern and

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

11

contemporary American poetry, even though this relationship has become

increasingly complicated. In Poetry and Commitment (2007), Rich emphasized the unique capacity of poetry to engage in social issues—a capacity that

is needed all the more urgently at a time of poetry’s comparable impotency:

For now, poetry has the capacity—in its own ways and by its own

means—to remind us of something we are forbidden to see. A forgotten

future: a still-uncreated site whose moral architecture is founded not on

ownership and dispossession, the subjection of women, torture and bribes,

outcast and tribe, but on the continuous redefining of freedom—that

word now held under house arrest by the rhetoric of the “free” market.

This on-going future, written off over and over, is still within view. All

over the world its paths are being rediscovered and reinvented: through

collective action, through many kinds of art. Its elementary condition is

the recovery and redistribution of the world’s resources that have been

extracted from the many by the few. (36)

It is true that, as Joseph Harrington has shown, even an organic workingclass intellectual such as the influential poet and labor activist of the 1910s,

Arturo Giovannitti, had to address various audiences and used established

poetic forms in order to make his voice heard in the public sphere (cf.

Harrington 105–26). And yet, although there is no simple link between

poetic expression and political activism, Giovannitti could take for granted

that his poetry was linked to the actions of the IWW (the Industrial Workers

of the World) and other labor activists. Rich equally insists that the “ongoing future [ . . . ] is still within view.” But there is a subtle difference in

tone: Rich emphasizes that the nexus between poetry and political activism,

between finding alternative paths and treating them, is currently “rediscovered and reinvented.” Her statement reflects that contemporary American

poetry has to struggle for political relevance at a time when political alternatives have largely disappeared from the public consciousness—at a time,

that is, when these alternatives have become a “forgotten future.” It is this

forgotten future that poetry must remember.

The relationship between the public sphere, social movements, and

poetic communities, as well as the variations in institutional settings and

practices and the presence and absence of literary, social, and political movements to which the individual poet can connect must be gauged carefully.

Although dedicated to the same poetics of global solidarity, the various

poets discussed in this book pursue different strategies and use different

literary methods according to their specific historical situation.7 Recent

sociological approaches to literature have shown that this historical moment

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

12

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

is refracted through the poets’ particular cultural and socioinstitutional

context. Mike Chasar has argued that “Americans living in the first half

of the twentieth century [ . . . ] lived in a world saturated by poetry of all

types and sizes” (4), a period in which “more people in the modern United

States were producing and consuming more verse than at any other time

in history [ . . . ]” (6). At the end of the twentieth century, by contrast, the

institutionalization of American poetry had forced contemporary writers to

address what Christopher Beach calls the “tension between the level of the

community and the level of the institution” (5). Poetry emerges as “a site for

the creation of community and value” (3, my emphasis), when in the early

twentieth century it could often rely on such communities and values for

institutional support.

It is necessary to consider these developments whenever we talk about

a particular political rhetoric or the choice of poetic form. The resurgence

of epic poetry in the 1950s, for instance, is also a response to the Cold War

liberal consensus and the crushing of influential social and political movements. It seemed inevitable for these poets to withdraw from politics temporarily to map a subject position beyond Cold War antagonisms. This is not

to say that other poetic forms were not available or produced; nor is it to say

that the epic form is a natural choice, or an epiphenomenon of a social or

cultural constellation. But the choice of poetic form at a particular historical

moment matters, since it also reflects the poet’s position in the social and

political struggles of the time.

My readings are therefore interested in the author’s choice of a particular form, in the (conscious or unconscious) social and political content of

the poem, and in how the poem’s social symbolism is related to the political imagination of antisystemic movements. In fact, social movements are

as important for an understanding of the engaged tradition of American

poetry as this poetry is for an understanding of these movements’ political

imagination. As Michael Denning has argued, “[m]ovements and countermovements continue to depend on philosophies of history, whether salvational histories of religious redemption, racial and national histories of

Aryan nations and white supremacy, or indeed narratives of uncompleted

revolution and eventual liberation” (Culture in the Age of Three Worlds 44).

In this context, an attention to form is especially significant. Rachel Blau

DuPlessis has emphasized that it is impossible “to analyze the meanings, ideologies and social-political functions associated with [objects, discourses, and

practices] in their time and across time ” (“Social Texts” 53) without paying

sufficient attention to form and to the text itself. DuPlessis therefore suggests an approach that she calls “social philology” (Genders 1). Similarly,

Michael Davidson has stressed “the implications of experimental form in

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

13

addressing the geopolitical meaning of poetry” and “the social and cultural

meaning of formal operations for specific communities that may exist on

the outskirts of the national imaginary” (Outskirts 5). An attention to poetic

form and to the texture of poetry is indispensable not only to do justice to

the complexities of poetic expression, but also to understand how poets link

themselves to poetic communities and, in the case of this book, the social

movements of a particular historical moment.

Although A Poetics of Global Solidarity is not primarily concerned with

the effectiveness of the poetic imagination in producing or inspiring social

movements or political activism, but rather with the cognitive mapping that

poetry can provide in such political contexts, any poetics that aligns itself

with social and political movements needs to face the question of what precisely its public and political role can be. Astrid Franke has identified the

desire for “public poetry” as a consistent factor in the history of American

poetry (cf. Franke). The left-leaning poets discussed here do not necessarily expect to reach out to “the public” at large, but they acknowledge, as

Sartre notes more generally, that the writer “has been invested, whether

he likes it or not, with a certain social function” (What Is Literature? 77).

The engaged poet actively seeks that function and thus assigns his or her

poetry a political value. In Making Something Happen, the title of which

plays on W. H. Auden’s famous dictum that “poetry makes nothing happen” (Auden 248), Michael Thurston analyzes political poets between the

two world wars to show how their poems were politically effective even if, on

the most basic level, this only meant that “poetry makes other poems (and

critical judgments) happen” (6). The writer need not necessarily influence

politics directly; only in extraordinary moments can literary aesthetics entail

what Russ Castronovo has called “the possibility of mass mobilization” (11).

Thurston’s book importantly reminds us that ideological change can occur

on a variety of planes—institutional, cultural, social, and political. Poets

can share in the global political discourses of the time while aiming for local

change.

These poets’ vision of global solidarity ultimately helps us fathom what

Robert Seguin has called “the possibilities and restrictions of historical form

and agency” at a particular historical moment (113). To see poetry through

its relationship with the modern world-system and the antisystemic movements responding to it cuts across established categories of literary scholarship, both synchronically and diachronically, revealing continuities where

we often see ruptures. As such this book connects with recent studies such as

Philip Metres’s, which reads war poems ranging from Whitman and Melville

to Langston Hughes’s poems about the Spanish Civil War as well as Barrett

Watten’s Bad History and Adrienne Rich’s “An Atlas of the Difficult World,”

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

14

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

both poems about the Gulf War, as “part of a larger human confrontation

with the violence, injustice, and oppressions that is in us and in our world”

(“With Ambush” 360; cf. Behind the Lines). This is not to simply abolish

differences between modernist and postmodernist activist poetry, but to see

them as responses to different stages of the same socioeconomic system.8

Such a perspective also contributes to an understanding of the alliances that

modern and contemporary American poetry seeks out in order to gauge

the possibilities and impossibilities of a global poetic subjectivity at various

moments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

To achieve this aim, however, theoretical readjustments are a necessary

but not sufficient condition. As John Newcomb has put it, to capture the

full diversity of modern American poetry, “[w]e need not only to surround

the old titans with fresh contexts but also to situate a much wider variety

of poets into those contexts” (“Out with the Crowd,” 251). To establish an

alternative, engaged tradition within twentieth- and twenty-first-century

American poetry, I therefore draw on canonic and neglected poets alike.

Only by recombining canonic figures with poets who are often not part of

literary histories will we be able to see the diversity of American poetry in a

particular historical period. The point here is not to establish a tradition of

political modernism against Eliot and Pound, or to propose an activist political poetry against lyrical poetry. The point is rather to argue that the engaged

poets tackled similar problems by different means and with different results,

and yet they were very much in conversation with, and inspired by, those

who were ultimately consecrated as the canonic poets of their time.

The extension of the poetic archive also benefits from a more expansive

definition of poetry. This broadening of poetic expression can enable us

to see links where we may not expect them. Many contemporary poetry

anthologies include song lyrics, and while some artists remain conflicted

about these parallels, others have embraced this confluence by republishing their song lyrics as Lyrics and Poems (Samson).9 More importantly, song

lyrics and poetry have frequently converged, and it seems unthinkable to

treat, say, the poetry of the Lyrical Left apart from the songs of the IWW,

Langston Hughes’s poetry apart from the Blues and jazz tradition, Allen

Ginsberg apart from Bob Dylan, or Amiri Baraka’s poetry apart from contemporary rap music. I am convinced that the inclusion of song lyrics helps

us to learn more about the various cultural and social functions of poetry,

and that literary critical methods can help us understand how multilayered

lyrics often are.

Both music and performance are fundamental for analyzing songs, but

they do not invalidate the analysis of song lyrics. In fact, the reprinting

of song lyrics in CD booklets designates them for circulation in a larger

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

15

cultural context—beyond performances on the stage, where they are often

unintentionally inaudible. Conversely, poetry is often more than “the printed

word”; it is often read and discussed in specific settings and thus part of

what Stanley Fish has called “interpretive communities” (483–85), socioinstitutional spaces such as the university classroom and social and cultural

movements.10 But most importantly, the song lyrics discussed here draw

and comment on the engaged tradition of American poetry. When Dylan

mentions Eliot and Pound, when Immortal Technique defines the mission

of hip-hop by way of an engagement with the Harlem Renaissance, and

when Strike Anywhere offer a self-definition of contemporary punk rock

by rewriting Shelley’s “The Mask of Anarchy,” it is well worth considering

such appropriations of poetic tradition because they both tell us something

about the diverse social uses of poetry and the use of poetic techniques in

song lyrics to produce meaning. Finally, these song lyrics display the same

desire to connect the poetics of global solidarity to a broader social movement that has underlain the engaged tradition of modern and contemporary

American poetry.

*

*

*

The following chapters discuss poets who map their historical moment while

simultaneously imagining a collective, global future beyond the status quo.

The first chapter, ‘“Blazing Signals of a World in Birth’: Lyrical Expression

and International Solidarity from the Literary Left to the Popular Front,”

investigates a moment in the history of American poetry when the poetic

imagination was inextricably linked to social and political movements. This

moment extends from the Lyrical Left of the 1910s to the Popular Front of

the 1930s. Arturo Giovannitti, Edwin Rolfe, and Muriel Rukeyser exemplify a poetic tradition whose poetics maps a global subject position that

refers the reader back to the industrial union movements of the 1910s and

the Popular Front of the 1930s, respectively. My intention behind combining Giovannitti, a poet writing in the context of the Lyrical Left and

the IWW in the 1910s, and Rolfe and Rukeyser, who are affiliated with

the Popular Front of the 1930s, is to show that the engagement with form

in the name of a vision of global solidarity remained a consistent factor

throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. Giovannitti’s “New

York and I” (1918), Rolfe’s “To My Contemporaries” (1935), and Rukeyser’s

“Mediterranean” (1938) decenter the lyrical voice into the structures that

sustain global capitalism. Simultaneously, they involve the poems’ speakers and, by implication, its readers in an alternative to the ideologies that

sustain global capitalism. Although lyrical speakers figure prominently in

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

16

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

their poetry, the carrier of the global poetic subjectivity in these poems is

no longer the individual poet, but a collective global subject that emerges by

way of a poetic rewriting of the individual through the imagination of the

powerful social and political movements of the time.

Just like the political modernist poets discussed in the first chapter, the

poets of the Harlem Renaissance wrote at a time when poetry was closely

linked to social and political activism. In the second chapter, “Global

Harlem: The Internationalism of the Harlem Renaissance,” I argue that

Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and

Claude McKay were internationalists who drafted a “map of the world”

(McKay, Home to Harlem 134) based on which they could imagine an active

role for African American culture within the context of the antisystemic

social and political movements of the 1920s and 1930s. These writers shared

a sense that the Harlem Renaissance was not only nationally significant,

but it was also a globally symbolic moment in the fight against discrimination, inequality, and poverty. In the context of social and political movements from the NAACP to the Communist Party and the various women’s

committees, these artists adopted a radical internationalism in response to

the institutionalized racism, gender divisions, and the class-structures of the

modern world-system.

The book then moves into the post–World War II era, which is characterized by the disintegration of the link between engaged poetry and

social movements. If Harlem Renaissance writers could regularly act with a

“map of the world” in their hands, the post–World War II liberal consensus

forced poets to rest content with such poetic mapping. The third chapter,

“Remapping America: The Epic Geography of Post–World War II American

Poetry,” discusses Thomas McGrath’s Letter to an Imaginary Friend (whose

first part was published in 1957), Norman Rosten’s The Big Road (1946),

and Melvin Tolson’s Libretto for the Republic of Liberia (1953), three epic

poems written during a crisis in the history of progressive social movements. As opposed to the classical epos of Homer and Virgil, which assisted

an emergent national identity, these poets destabilize nation-centered and

nationalist ideologies, assigning the United States a more modest role in

the parliament of nations. McGrath’s autobiographical journey into the past

creates a representative hero who realizes that the present needs to activate

potentials of resistance from the past; Rosten establishes a symbolic road that

becomes the heroic manifestation of the contradictions that the expansion

of the world-system produced throughout the centuries; and Tolson refracts

Western culture through Liberia, creating a heroic vision of a transnational

parliament of humankind, a “cosmopolis of/ Höhere” (Libretto 183). The

epic form here dissolves the nation-state, remapping it onto the modern

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

17

world-system. These poems figure as a temporary refuge from which new

ways of seeing America’s role in the post–World War II world can emerge

and suggest new strategies to envision a global solidarity.

The fourth chapter, “From Cuba to Vietnam: Anti-Imperialist Poetics

and Global Solidarity in the Long Sixties,” shows that with the emergence of

the Civil Rights Movement and “the Movement” (cf. Terry Anderson) in the

long Sixties, the time period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, political

poets found themselves again thrust into the public sphere. In this chapter,

I trace the anti-imperialist poetic imagination of the 1960s that emerged

in the context of two major global political events: the Cuban Revolution

and the Vietnam War. Both of these events sparked an anti-imperialist and

often anticapitalist political poetry. Even before Vietnam, Cuba invited the

global poetic imagination of American radicals to consider alternatives to a

consumerist Western world and to global capitalism. All of the poets and

lyricists discussed in this chapter, from Bob Dylan to Lawrence Ferlinghetti,

Allen Ginsberg, and Denise Levertov, were involved in the social movements

of the 1960s. The sea changes in world politics and the constitution of the

New Left with its liberation politics not only enabled new coalitions but also

made it more difficult to place one’s poetry in the context of often contradictory social movements. The poets discussed here attempted to forge the

(often contradictory) impulses of various social movements into an enabling,

antisystemic poetics of resistance.

The legacy of these earlier literary movements is discussed in chapters 5

and 6. Both present poems and song lyrics that often do not figure prominently in literary histories which center on experimental, language-oriented

poetry and the lyric mode as the two dominant forms of contemporary

poetry. The poems analyzed here express the desire for a new coalition of

forces that is both inspired by and reconsiders the legacy of earlier poetic and

social movements from the Popular Front and the Harlem Renaissance to

Third World liberation movements. In chapter 5, “Contemporary American

Poetry and the Legacy of the Third World,” I analyze the poetry of African

American poet Amiri Baraka, Chicano poet Luis J. Rodríguez, and the

lyrics of American Peruvian rapper Immortal Technique as well as AsianAfrican American rap group Blue Scholars. These poets and lyricists carry

over the heritage of cultural nationalism and the political legacy of Third

World liberation movements into a global poetic subjectivity that addresses

the conditions of global poverty in the twenty-first century. All of these

poets deal with the disappearance of Third World liberation movements

and imagine possible global coalitions that can become the successor of

these liberation movements, working from a broader, more inclusive basis.

In their attempts to create a new poetics of inclusion, they exemplify Hardt

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

18

●

A Poetics of Global Solidarity

and Negri’s assessment of a growing wave of cultural and political workers

believing that “revolutionary politics can begin with identity but not end up

there” (Hardt/Negri, Commonwealth 332).

Chapter 6, “Contemporary American Poetry, Literary Tradition, and

the Multitude,” continues this exploration of a form of contemporary

poetic expression that rewrites the impulses of earlier literary movements

into the imagination of a multitude. The poems and song lyrics analyzed

in this final chapter illustrate an ongoing commitment to global solidarity following the end of the Cold War. From the 1990s on, there is a

continuous effort to imagine a global poetic subjectivity inspired by the

antiglobalization movements. Whether in Mark Nowak’s long workingclass poem Coal Mountain Elementary (2009), Anne Waldman’s feminist

Iovis-trilogy (1993–2011), or melodic hardcore band Strike Anywhere’s

lyrics, we find an attempt to poetically map a historical moment of transition that escapes the individual’s cognitive abilities, and to give expression

to an emergent, often inchoate or incomplete collective subjectivity capable of confronting this constellation. The three modes of poetic expression I identify—Nowak’s documentary poetics in the tradition of Muriel

Rukeyser, Waldman’s collective autobiography, and Strike Anywhere’s

Romantic rhetoric of revolution—emerge from these authors’ engagement

with tradition. While they acknowledge the fact that new forms of protests

are necessary (if only for the problems and contradictions of older social

movements), they stress the necessity to maintain the heritage of social

resistance stored in the history of poetry. This imagination of a collective

subjectivity is predicated on the powerful fiction that the various social

movements will unite beyond the sectarian divides that have characterized

many of these movements in the past. By bringing together the poems and

lyrics discussed in this chapter, I focus on an important strand in contemporary American poetic expression that searches for poetic communities

and links poetic expression to broader cultural and social movements.

These texts show that the desire to connect poetic expression and political activism and social movements persists. The conclusion returns to

Adrienne Rich’s diagnosis of a postmodernity characterized by political

apathy. In “Benjamin Revisited” from her last collection Tonight No Poetry

Will Serve (2011), Rich replaces Benjamin’s angel of history with a janitor

sweeping away the remnants of history and political engagement, “stoking/

the so-called past/ into the so-called present” (17). While Rich’s poem,

and her poetry in general, is a trenchant indictment of cynical postmodern detachment, it is also a comment on the desirability and necessity of a

broad coalition of engaged poets. The conclusion discusses how, in order

to capture the future potential of engaged poetry, it is necessary to define

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Introduction

●

19

poetic expression more broadly, to continuously extend the textual archive,

and, finally, to situate American poetry in a global context. The rearrangement of different poets along the lineages suggested by their affiliation

with the social and political movements of the twentieth and twenty-first

centuries can help establish new, unforeseen constellations and reveal the

enduring cultural and political relevance of an engaged poetics of global

solidarity.

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Index

African Blood Brotherhood, 77

Alcan Highway, 99–105

Alighieri, Dante, 109

All-African People’s

Conference, 224n.3

American Coal Foundation, 183–4

American Colonization Society,

106, 109

American Federation of

Labor (AFL), 32

Annand, George, 98–9, 105–6

anticolonization movements, 106

anticommunism, 86, 97–8, 220n.14

antiglobalization movement, 3, 18,

166, 177, 199, 201, 206

World Trade Organization

Conference, Seattle 1999, 169

Appian Way, 99, 101

Aristotle, 89

Arrighi, Giovanni, 119–20, 145, 182,

211–12, 226n.1, 226n.2

Ashmun, Jehudi, 109

Auden, W. H., 13

Autoworker, 178–9

Aztlán, 162

Bagong Alyansang Makabayan

Movement (BAYAN), 166

Baha’i, 166

Bakhtin, Mikhael, 122, 222n.8

Bambaata, Africa, 224n.7

“Planet Rock,” 224n.7

Bandung Conference, 107

Baraka, Amiri, 147–58, 161, 164, 172,

179, 182, 211, 223–4n.2, 224n.5

“Class Reunion,” 182

“Cuba Libre,” 150

“In the Tradition,” 152–4

Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide

Note, 150

“Somebody Blew Up America,” 150

“‘There Was Something I Wanted to

Tell You.’ (33) Why?,” 155–6

“Wise, Why’s, Y’s,” 154–5

Barcelona, 46, 49, 81–2

Barnett, Thomas, 201

see also Strike Anywhere

Basie, Count, 153

Beat Poetry, 120, 124–37, 150, 176,

190, 192, 221n.1

Benjamin, Walter, 100, 209–10

“Theses on History,” 209–10

Bering, Vitus, 102

Bering Strait, 99–103

Berkeley, 136, 138, 142–3

Bloody Thursday, 142

People’s Park, 136, 138, 142–3,

223n.20

Bernstein, Charles, 75

Birth of a Nation, 151

Black Arts Movement, 148–50, 152–3

Black Mountain School, 114, 139, 192

Black Nationalism, 8, 82, 148–52, 171

Black Panther Party, 148

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

248

●

Index

Black Star, 165

Blake, William, 88, 202

“London,” 202

Blue Jays, 15

Blue Scholars, 147, 165–70, 211–12,

224n.8

“50k Deep,” 169

Bayani, 166–9

“Bayani,” 167–9

Cinémetropolis, 224n.8

“Opening Salvo,” 166–7, 212

“Second Chapter,” 166

Blues, 14, 44, 153

Bly, Robert, 137

Blythe, Arthur, 152

Boone, Daniel, 99

Boston Five, 137

boysetsfire, 209

The Misery Index, 209

Bradstreet, Anne, 72

“The Author to Her Book,” 72

Brathwaite, Edward Kamau, 74–5

Brecht, Bertolt, 59

“Questions of a Worker Who

Reads,” 59

broadsides, 118, 126, 148

Browder, Earl, 23, 88

Buddhism, 136, 190–5

Burke, Kenneth, 213

Bush, George W., 191

Casa de las Américas, 130

Castro, Fidel, 120, 125–30, 221n.3

Castro, Raúl, 119

Chaplin, Ralph, 21

“Solidarity Forever,” 21

Chase, Richard, 98

Chicano Moratorium against the

Vietnam War, 157

Chomsky, Noam, 137

Ciardi, John, 221n.9

Dialogue with an Audience, 221n.9

Cinderella, 121–2

City Lights bookstore, 124

Civil Rights Movement, 117–18

Clash, The, 178, 201

Sandinista!, 201

Cloots, Anacharsis, 93–4

Coffee House Press, 190

cognitive mapping, 6–7, 13, 212, 214

Cold War, 12, 66, 86–8, 94–9, 104,

109–14, 117, 124–6, 224n.3

see liberal consensus

Collins, Judy, 138

Coltrane, John, 153

Common, 165

Communist International, 54–5

Communist Party of the United

States of America (CPUSA), 55,

88, 126

Cortés, Hernán, 162, 220n.6

Council for Democracy, 97

Crane, Hart, 88

Creedence Clearwater Revival, 203

“Fortunate Son,” 203

Creeley, Robert, 114

Crisis, The, 59, 67, 69, 72, 80, 219n.6,

219n.12

Cuba/Cuban Revolution, 117–37

Cullen, Charles, 73

Cullen, Countee, 54, 73, 220n.15

The Black Christ, 73

Caroling Dusk, 220n.15

cultural front, 35–6

cultural nationalism, 35, 42, 54–6,

75–6, 83, 147–73

Daily Worker, 23, 34, 137

Davis, Bette, 122

Davis, Mike, 149

Debray, Régis, 125

Foco theory, 125, 128

Revolution in the Revolution?, 125

Declaration of Independence, 126

Deep Cover, 1–2

Defoe, Daniel, 200

A Journal of the Plague Year, 200

Dell, Floyd, 27

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Index

Democratic Party, 45, 61

see Popular Front; Roosevelt,

Franklin Delano

Dessau, Paul, 42

“Die Thälmann-Kolonne,” 42

Di Prima, Diane, 118–20

Revolutionary Letters, 118–20

DJ Kool Herc, 224n.7

documentary poetry/documentary

mode, 44, 62, 98, 188–90

Dorsey, Thomas A. (Georgia

Tom), 154

Dos Passos, 21–2

U.S.A., 21–2

Du Bois, W. E. B., 67–71, 76–7, 113,

218n.1, 218n.2, 219n.7

“Criteria of Negro Art,” 70–1

Foreword to Johnson’s Bronze, 67–8

“The African Roots of War,” 113,

219n.7

“Two Novels,” 218n.1

Dulles, John Foster, 133

Dunbar-Nelson, Alice, 56, 67–74,

219n.10, 219n.11

“I Sit and Sew,” 68–9

“The Proletariat Speaks,” 69–71

Duncan, Robert, 143, 223n.19

Dylan, Bob, 14–15, 119–24, 137, 143,

222n.7, 222n.9

“Desolation Row,” 119–24

Highway ‘61 Revisited, 121

“Masters of War,” 121

“Only a Pawn in Their Game,” 121

Dynamo, 35–6, 43, 102

Eastman, Max, 26–7, 59

Einstein, Albert, 122–3

Eisenhower, Dwight D., 119

El Movimiento, 157, 164

Eliot, T. S., 3, 10, 14–15, 28–9, 38,

41–2, 50, 82, 88, 93, 108–9,

122–3, 194, 213, 217–18n.11

“The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock,” 29–30, 82, 123

●

249

“Tradition and the Individual

Talent,” 28–9, 38

The Waste Land, 42, 50, 109, 194,

218n.14

Ellis Island, 94

Emanuel, James A., 148–9

“At Bay,” 148–9

Engels, Friedrich, 182

epic poetry (epos), 12, 86–92, 114–15

equidistant azimuthal projection, 98

Esperanto, 112–13

Ettor, Joseph, 22

Fair Play for Cuba Committee

(FPCC), 126, 129, 131, 150

Fearing, Kenneth, 24

“Dirge,” 24

Federal Theatre Project, 61–2

Ethiopia, 61

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence, 118–20,

124–37, 142, 150, 222n.10,

222n.12

After the Cries of the Birds, 135–7

Americus, Book II, 124

A Coney Island of the Mind, 125–6

“Note on Poetry,” 118

One Thousand Fearful Words for

Fidel Castro, 126–9

Time of Useful Consciousness, 124

“Where Is Vietnam?,” 135

Firestone Rubber and Tire

Company, 106

Fish, Stanley, 15

foco theory, 125, 128

Ford autoworkers, 178–9

Freeman, Joseph, 23, 33–7

French Revolution, 53, 94

Fuller, Hoyt W., 148–9

“Towards a Black Aesthetic,” 148–9

Funaroff, Sol, 35, 39–41, 102–3

“The Bellbuoy,” 102–3

G. I. Bill, 86

Galeano, Eduardo, 163

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

250

●

Index

Garvey, Marcus, 106, 165, 221n.8

geoculture, 7–8

Ginsberg, Allen, 14, 119–20, 124–37,

150, 222–3n.13, 223n.14

“A Vow,” 132, 134

“America,” 136

“Howl,” 124, 132

“Message II,” 130–1

Prose Contribution to Cuban

Revolution, 130–1

“Wichita Vortex Sutra,” 132–5

Giovannitti, Arturo, 11, 22–34, 38, 50,

56, 210, 213

Arrows in the Gale, 23, 25–6, 217n.4

“May Day in Moscow,” 26

“New York and I,” 27–31

“O Labor of America: Heartbeat of

Mankind,” 31–2

“The Walker,” 25

“To Helen Keller,” 26

global poetic subjectivity, 4–6, 8

Gold, Michael, 23, 34–6

“Go Left Young Writers,” 35

“Toward Proletarian Art,” 35

Golden, John, 32

Gompers, Samuel, 32

Gonzales, Rodolfo, 149, 157,

162, 224n.6

“I am Joaquín,” 149, 157, 162

Goodman, Mitchell, 137

gopher, 92–3

Gordon, Don, 92

Great Depression, 5, 9, 33–6, 57

Green Party, 158

Grimké, Angelina Weld, 57

Gropper, William, 79

Guevara, Ernesto “Che,” 125, 129

Guido of Arezzo, 113

Guthrie, Woody, 186

“This Land Is Your Land,” 186

Haile Selassie Gugsa, 63–4

Hampton, Fred, 155

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri,

17–18, 149, 176–7, 181, 187, 193,

201, 211–12

Harvey, David, 179

Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster, 24,

43, 49

Hayden, Robert, 166

Hemingway, Ernest, 10

Hiatt, Ben L., 222n.5

Poems—Written in Praise of LBJ,

222n.5

Hill, Joe, 21, 32

“John Golden and the Lawrence

Strike,” 32

Hip-hop, 164–73

Holocaust, 92

Homer, 87

Hopi religion, 91

Hughes, Langston, 8–10, 13–14,

16, 23, 55–67, 73, 80–1,

218–19n.4

“Advertisement for the

Waldorf-Astoria,” 8

“Air Raid Over Harlem,” 61–7

“Christ in Alabama,” 73

“Johannesburg Mines,” 57–8

“Letter From Spain,” 58

“Proem” (“The Negro”), 59

“Question [1],” 59–60

“The Negro Artist and the Racial

Mountain,” 57, 218–19n.4

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers,”

59–61, 66

The Weary Blues, 59

Hurston, Zora Neale, 57

Immortal Technique, 1–2, 15, 147,

169–73, 211

The 3rd World, 1–2

“Golpe De Estado,” 1

“Harlem Renaissance,” 170–2

“That’s What It Is,” 2

“The 3rd World,” 169–70

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Index

Industrial Workers of the World

(IWW), 11, 14, 21, 24, 27, 32–3,

50, 201

International Brigades, 42

International Ladies Garment Workers

Union (ILGWU), 26

International Monetary Fund (IMF),

169, 172

Iraq War, 197

Iron Front, 203–4

James, C. L. R., 94

Jameson, Fredric, 6–7, 119, 143, 213,

216n.5

jazz, 14, 37, 39, 57, 152–3

John Reed Clubs, 35

Johnson, Georgia Douglas, 55–6,

67–8, 71–4

“Black Woman,” 71–2

Bronze, 71–2

“Cosmopolite,” 72–3

“The True American,” 73–4

Johnson, James Weldon, 54

Johnson, Lyndon B., 132–3, 135

Justice Party, 158

Keats, John, 37–8

“Ode to a Nightingale,” 37–8

Keller, Helen, 26, 217n.4

Kerouac, Jack, 225n.10

King, Martin Luther, 120

King, Rodney, 158

Kipling, Rudyard, 113

“Recessional,” 113

Klee, Paul, 209

Kramer, Aaron, 86

language poetry, 176

Lauter, Paul, 137

Lawrence textile strike, 22, 25, 31

League of Revolutionaries for a New

America, 157–8

People’s Tribune, 157–8

●

Levertov, Denise, 120, 137–45

“At the Justice Department,

Nov. 15, 1969,” 143

“Biafra,” 144

“Life At War,” 139–41

The Sorrow Dance, 139, 141–2

To Stay Alive, 139, 141–3

“The Distance,” 144–5

“The Pulse,” 141–2

Levertov Olga, 137, 139–40

Lewis, John, 120

liberal consensus, 12, 85–8, 114,

117, 126

Liberator, The, 22, 25–7,

29, 77–9

Lieber, Maxim, 67

Lindsay, Vachel, 23

littérature engage, 3–15, 206

Little Red Songbook, 32

living newspaper, 61

Locke, Alain, 54–5, 67, 82

The New Negro, 67

“The New Negro,” 54–5

London, Jack, 73

Los Angeles Janitor’s Strike,

2000, 164

Los Angeles Riots, 1992, 158

Lowell, Robert, 117

“Memories from West Street and

Lepke,” 117

Lowenfels, Walter, 86

Lyrical left, 22–5, 33–4, 50

Macy, Anne Sullivan, 26

Malcolm X, 153

March on Washington for Jobs and

Freedom, 120

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, 26–7

“Futurist Manifesto,” 26–7

Marx, Karl, 7, 36, 182

Communist Manifesto, 182

MC Globe, 224n.7

McCarthyism, 88

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

251

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

252

●

Index

McGrath, Thomas, 86–97, 99, 106–7,

112, 114, 119, 131, 194

Letter to an Imaginary Friend,

86–97, 114

pseudo-autobiography, 90, 114, 194

strategic and tactical poetry, 87

McKay, Claude, 26, 53–7, 74–83, 217n.5

“Barcelona,” 81–2

“Exhortation: Summer, 1919,” 78

Harlem Shadows, 77–8

“Harlem Shadows,” 78, 79

“He Who Gets Slapped,” 79

Home to Harlem, 53–5

“If We Must Die,” 26, 78

A Long Way From Home, 80–1

“Peasants’ Ways o’ Thinkin’,” 75–7

“The Harlem Dancer,” 78, 79

“The International Spirit,” 79–80

“The Tired Worker,” 78

“To Ethiopia,” 78–9

Medical Bureau and North American

Committee to Aid Spanish

Democracy, 46

Merriam, Eve, 86

Merwin, W. S., 137

Messenger, The, 55, 57, 59

Mills, C. Wright, 118

modernism, 3, 14, 25–8, 31–2, 35–6,

42–3, 46, 61, 65, 86–9, 96–8,

108, 115, 122, 194, 213

Monroe, Harriet, 25

Moratorium March on Washington, 143

Morello, Tom, 201

The Nightwatchman, 201

Motown, 170

multitude, 164, 176–8, 181, 201–3,

205, 212

Mussolini, Benito, 48, 61

Myrdal, Gunnar, 110

An American Dilemma, 110

Nancy, Jean-Luc, 6, 211

Nation, The, 218–19n.4

National Council of Teachers of

English, 188

National Liberation Front, 144

Nelson, Cary, 3, 34–5, 217n.6, 219n.5

Neruda, Pablo, 222n.5

New Criticism, 88

New Left Review, 221n.3

New Masses, 8, 10, 23, 35, 43, 46, 97

New York School, 192

New York Times Book Review, 44, 114

New Yorker, 114

North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA), 160, 179, 195

Nowak, Mark, 2, 5, 51, 175–91, 197,

200–1, 204, 206, 211

Coal Mountain Elementary, 2, 51,

175, 178–80, 183–91

“June 19, 1982,” 181–2

“Notes Toward and Anti-Capitalist

Poetics,” 179, 188

“Notes Toward and Anti-Capitalist

Poetics II,” 179

Revenants, 180

Shut Up Shut Down, 180–3

Nuyorican Café, 165

Obama, Barack, 119

Occupy, 177, 190, 201

Olson, Charles, 192

Ophelia, 122–3

Orlovsky, Peter, 130–1

Owen, Chandler, 55

“The New Negro—What

is He?,” 55

Pa’ lante: Poetry Polity Prose of a New

World, 131

Pan-Africanism, 55, 77, 106, 152

Paris Commune, 154–5

Pearl Harbor, 105

pedagogical dimension of art, 6–7

Penguin, 190

Peoples’ Olympiad, 43, 47

Pindar, 108, 113

Pizarro, Francisco, 99, 101, 220n.6

Plessy versus Ferguson, 60

poetic archive, 14, 213–14

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Index

poetic communities, 10–15, 18, 117,

125, 135–7, 142, 144, 178, 206

poetics of global solidarity, definition,

1–6, 9–10

Poetry, 25

Poetry Project (St. Mark’s Church in

Manhattan), 190

Popular Front, 3, 10, 22–4, 33–5,

41–5, 49–50, 57–8, 61, 67, 85–6,

97, 102, 131, 211

see also cultural front

Pouget, Emile, 33, 217n.9

Sabotage, 33

Pound, Ezra, 3, 14, 15, 25, 87–8, 98,

122, 194, 213

“A Few Don’ts By An Imagiste,” 25

The Cantos, 87–8, 98

proletarian poetry, 10, 35, 97–8

Proust, Marcel, 93

Public Enemy, 169

punk/hardcore punk, 15, 176, 200,

207, 226n.13

Rainey, Ma, 154

Randolph, A. Philip, 55

“The New Negro—What is He?,” 55

Reagan, Ronald, 142, 180

Bloody Thursday, 142

Reed, Adolph, Jr., 171

Reed, Ishmael, 152

Reed, John, 27

RESIST, 137

Revolution on Canvas, 200

Rexroth, Kenneth, 221n.3

Rich, Adrienne, 7, 10–11, 179, 209–12

“Benjamin Revisited,” 209–10

“Credo of Passionate Skeptic,” 7

“North American Time,” 10–11, 209

Poetry and Commitment, 11, 210–12

Rineheart and Company, 98

Rodríguez, Luis, 147, 157–64, 168,

172, 179, 211

Always Running, 157

“Fire,” 162–3

It Calls You Back, 157

●

253

“My name’s not Rodríguez,” 162

“Running to America,” 160–2, 168

“¡Si, Se Puede! Yes, We Can!,” 164

“Watts Bleeds,” 159–60

Rolfe, Edwin, 5, 8–10, 23–4, 33–43,

50, 56, 86, 92, 102, 123, 213

“Credo,” 36–7

“Death By Water,” 42

“Entry,” 42

First Love and Other Poems, 34, 42

“Georgia Nightmare,” 36

“Homage to Karl Marx,” 36

“Kentucky,” 36

“Letter for One in Russia,” 36

To My Contemporaries, 23, 35–6

“Poetry,” 23, 35, 41

“Room with Revolutionists,” 41

“Seasons of Death,” 33–4

“These Men Are Revolution,” 8–9

“To My Contemporaries,” 24,

36–42, 123

“Witness at Leipzig,” 36

Romanticism, 24, 28–9, 34, 35–42, 71,

202–3

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano, 45, 48

Ross, Diana, 170

“Brown Baby,” 170

Rossman, Michael, 145

Rosten, Norman, 50, 85–7, 97–107,

114–15, 119, 221n.7

The Big Road, 50, 86, 97–106

Rukeyser, Muriel, 22–4, 56, 86, 98,

137, 176, 179, 183

“George Robinson: Blues,” 44

Life of Poetry, 44–5

“Mediterranean,” 24, 43, 46–9

“Night-Music,” 44

“Praise of the Committee,” 44

“The Book of the Dead,” 24, 43–6,

49–50, 98, 176, 179, 183

“The Cruise,” 46

“The Lynchings of Jesus,” 43

Theory of Flight, 43

U.S.1, 43–6, 48, 50

Russian Revolution of 1917, 26, 78

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

Copyrighted material – 9781137568304

254

●

Index

Sacco, Nicola, 22

Sago Mine Disaster, 183–4

Samson, John K., 14

San Francisco Renaissance, 124, 142

Sandburg, Carl, 23, 28, 32

“Chicago,” 32

Sanders, Ed, 130

Santamaria, Haydée, 130