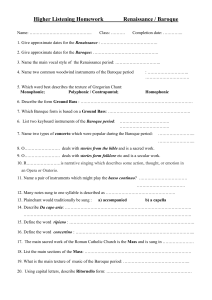

ITALIAN BAROQUE

advertisement

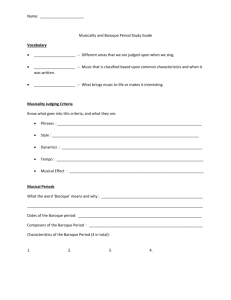

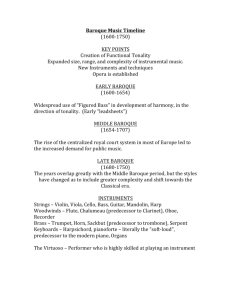

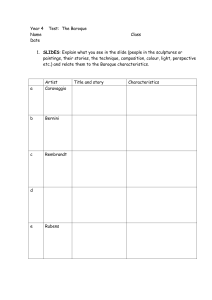

ITALIAN BAROQUE ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Concepts to know… Patrons and their influence on art How did royal patrons of the arts choose to have themselves portrayed in the art of the seventeenth century? Comparing the art of painters such as Riguard, Van Dyck, Rubens, and Velazquez will help students to visualize the changes that had occurred since the Renaissance. Regional differences should also be noted. Naturalism/verisimilitude The desire of seventeenth-century painters to achieve naturalism in their works marks a shift away from Classical ideals. The willingness of patrons to be portrayed, "warts and all" (p. 752), is a startling shift from the trends first seen in the art of the ancient Near East. Caravaggio takes this notion to an extreme, and was famously persecuted because of it. New patrons The emergence of a middle-class art-buying public in Holland during this period is an extraordinary development. The Calvinistic mores of that culture need to be closely scrutinized to understand the laces in their portraits and the oysters in the still lifes of the period (p. 799). Shifting styles This chapter includes the Baroque and the Rococo art styles. The reasons, not fully understood, for this shift in taste and what it means visually, are of major importance. Unlike Mannerism, the Rococo style is mostly uniform, and quickly identified. Nonetheless, the chapter provides opportunities for students to practice connoisseurship—for example, in a comparison of Watteau and Boucher. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque People to know… ITALIAN Bernini, Borromini, Caravaggio, Gentileschi FRENCH Louis XIV, Poussin, Lorrain SPANISH Philip IV, Velazquez FLEMISH Rubens, Van Dyck, Charles I DUTCH Hals, Ruisdael, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Claesz ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Goals of Art during the COUNTER-REFORMATION (The “Empire Strikes Back”) To deliberately evoke intense emotional response from the viewer ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Goals of Art during the COUNTER-REFORMATION (The “Empire Strikes Back”) To deliberately evoke intense emotional response from the viewer To create dramatically lit, often theatrical compositions ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Goals of Art during the COUNTER-REFORMATION (The “Empire Strikes Back”) To deliberately evoke intense emotional response from the viewer To create dramatically lit, often theatrical compositions To use diverse media such as bronze and marble within a single artwork ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Goals of Art during the COUNTER-REFORMATION (The “Empire Strikes Back”) To deliberately evoke intense emotional response from the viewer To create dramatically lit, often theatrical compositions To use diverse media such as bronze and marble within a single artwork To create work with spectacular technical virtuosity ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Bernini Gianlorenzo BERNINI His works include: ▪ The colonnade of St. Peter’s Piazza ▪ The baldacchino on the St. Peter’s altar ▪ Vibrant marble sculpture of David ▪ Ecstasy of St. Theresa sculpture ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Gianlorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino, St. Peter’s, Rome. 1623-1634. Long before the planning of the Piazza, Bernini had been at work decorating the interior of Saint Peter’s. His first commission, completed in 1624 and 1633, called for the design and erection of the gigantic bronze baldacchino ( a canopy made of cloth or stone erected over an altar, shrine, or throne in a Christian church) above the main altar under the great dome. The canopy-like structure marks the tomb of Saint Peter. At almost one hundred feet high it serves as a focus of the church’s splendor. At the top of the columns four colossal angels stand guard at the upper corners of the canopy. Forming the canopy’s apex are four serpentine brackets that elevate the orb and the cross, symbols of the Church’s triumph since the time of Constantine. All over the baldacchino are letter B’ s representing the Barberini family (Pope that commissioned the work). ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Gianlorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino, St. Peter’s, Rome. 1623-1634. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Gianlorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino, St. Peter’s, Rome. 1623-1634. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Giovanni Panini, Interior of St. Peter’s, Rome, 1731. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Gianlorenzo Bernini, “David”, Galleria Borghese, Rome, 1623. Bernini’s sculpture is expansive and dramatic, and the element of time usually plays an important role in it. This marble statue aims at catching the figure’s split-second action and differs markedly from the restful figures of David portrayed by Donatello and Michelangelo. The figures legs are widely and firmly planted, beginning the violent, pivoting motion that will launch the stone from his sling. If the action had been a moment before, his body would have been in a completely different position. Bernini selected the most dramatic of an implied sequence of poses, so observers have to think simultaneously of the continuum and of this tiny fraction of it. This is not the kind of sculpture that can be inscribed ITALIAN BAROQUEin a cylinder or confined in a niche; its Italian Baroque Comparing Davids…. Donatello Michelangelo Bernini (Early Italian Renaissance) (High Italian Renaissance) (Italian Baroque) ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Church of the Santa Maria della Vittoria (Cornaro Chapel) ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Gianlorenzo Bernini “Ecstasy of Saint Theresa”, Bernini Cornaro Chapel, Rome Italy, 1645-1652 Saint Theresa was a nun of the Spanish Counter-Reformation. Her conversion occurred after the death of her father, when she fell into a series of trances, saw visions, and heard voices. Feeling a persistent pain, she attributed to “the fire tipped arrow of Divine love” that an angel had thrust repeatedly into her heart. In her writings, Saint Theresa described this experience as making her swoon in delightful anguish. The whole chapel became a theater for the production of this mystical drama. Bernini depicted the saint in ecstasy, unmistakably a mingling of spiritual and physical passion, swooning back on a cloud while the smiling angel aims hisITALIAN arrow. BAROQUE Italian Baroque Bernini, “Ecstasy of Saint Theresa”, Cornaro Chapel, 1645-1652 ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Aerial view of St. Peter’ s in Rome ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque View of the Square from St. Peter’s Dome ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Carlo Maderno, “Santa Susanna” Rome, Italy 1597-1603. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Comparing buildings… BAROQUE Santa Susanna MANNERISM il Gesu ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Restoring Saint Peter’s, Vatican City, Rome, Italy ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Francesco Borromini, facade of “San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane”, Rome, Italy, 1665-1676. The church was designed by the architect Francesco Borromini and it was his first independent commission. Designed as part of a small monastery for a community of Spanish monks, it is an iconic masterpiece of Baroque architecture. Built to fit in a cramped and difficult site, the church has an unusual and somewhat irregular floor plan in the shape of a Greek cross defined by convex curves. The facade is similarly undulating in plan, and this effect was subsequently adopted by other Baroque architects in their church designs. The unifying design feature in the interior is the use of the triangle, a motif for the Trinity. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Francesco Borromini, facade of “San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane”, Rome, Italy, 1665-1676. The interior of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane is not only an ingenious response to an awkward site but also a provocative variation on the theme of the centrally planned church. In the plan, San Carlo looks like a hybrid of a greek cross and an oval, with a long axis between entrance and apse. The side walls move in an undulating flow that reverses the façade’s motion. Vigorously projecting columns define space into which they protrude just as much as they do the walls attached to them. This molded interior space is capped by a deeply coffered oval dome that seems to float on the light entering through windows hidden in its base. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Francesco Borromini, interior of “San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane”, 1665-1676. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Michelangelo Merisi (Caravaggio), Conversion of Saint Paul , 1601. Caravaggio painted Conversion of Saint Paul for the Cerasi Chapel in the Roman church of Santa Maria del Popolo. It illustrates the conversion of the Pharisee Saul to Christianity, when he became the disciple Paul. The saint-to-be appears amid his conversion, flat on his back with his arms thrown up. In the background, an old hostler seems preoccupied with caring for the horse. At first inspection, little here suggests the momentous significance of the spiritual event taking place. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio Conversion of Saint Paul, 1601 On display at the Santa Maria del Popolo (Rome, Italy) ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “Calling of Saint Matthew” c1597-1601 The painting depicts the story from the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 9:9): "Jesus saw a man named Matthew at his seat in the custom house, and said to him, "Follow me", and Matthew rose and followed Him." Caravaggio depicts Matthew the tax collector sitting at a table with four other men. Jesus Christ and Saint Peter have entered the room, and Jesus is pointing at Matthew. A beam of light illuminates the faces of the men at the table who are looking at Christ. In this work Caravaggio draws inspiration from his own world, placing the biblical scene in modern reality. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “Calling of Saint Matthew” c1597-1601 In this work Caravaggio draws inspiration from his own world, placing the biblical scene in modern reality. This work is evidence of Caravaggio's artistic confidence. He was not comfortable with the traditions of contemporary idealizing history painting and so he regressed to the subjects of his youth which had previously earned his success. Additionally, in this work, there is a likeness between the gesture of Jesus as pointing towards Matthew and that of God as he awakens Adam in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “Calling of Saint Matthew” c1597-1601 The Calling of Saint Matthew can be divided into two parts. The figures on the right form a vertical rectangle while those on the left create a horizontal block. The two sides are further distinguished by their clothing and symbolically, by Christ's hand. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “Calling of Saint Matthew” c1597-1601 ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggo, Crucifixion of St. Peter, c1600. Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. The painting depicts the martyrdom of St. Peter by crucifixion. Peter asked that his cross be inverted so as not to imitate his God, Jesus Christ, hence he is depicted upside-down. The large canvas shows Romans on Nero’s behalf, their faces shielded, struggling to erect the cross of the elderly but muscular apostle. Peter is heavier than his aged body would suggest, and his lifting requires the efforts of three men, as if the crime they perpetrate already weighs on them. dark, impenetrable background draws the spectator's gaze back again to the sharply illuminated figures, yet the faces of Romans are hidden – perhaps in shame. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Michelangelo, Crucifixion of St. Peter Contrast the two Crucifixions Caravaggio, Crucifixion of St. Peter, c1600. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, Flagellation of Christ. c.1606-1607. Oil on canvas. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ, 1602. "The one I shall kiss is the man; seize him and lead him away safely" (Mark 14:44). ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “Supper at Emmaus” National Gallery, London 1601. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Caravaggio, “The Incredulity of St. Thomas”, 1602. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Beyond its ability to move its audience, this composition also had theological implications. To viewers in the chapel, it appeared as though the men were laying Christ’s body onto the altar, which was in front of the painting This served to visualize the doctrine of transubstantiation (the transformation of the Eucharist and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ) -- a doctrine central to Catholicism but rejected by Protestants. By depicting Christ’s body as though it were physically present during the Mass, Caravaggio visually articulated an abstract theological precept. Unfortunately, viewers no longer can experience this effect. Caravaggio, “Entombment” 1602-1603. ITALIAN BAROQUE You go, girl! Italian Baroque Artemisia Gentileschi “Judith Slaying Holofernes” ca. 1614-1620 Gentileschi used what might be called the “dark” subject matter Caravaggio that favored. Significantly, Gentileschi chose a narrative involving a heroic female, and favorite theme of hers. The story, from the Book of Judith, relates the delivery of Israel from its enemy, Holofernes. Having succumbed to Judith’s charms, the Assyrian general Holofernes invited her to his tent for the night. When he fell asleep, Judith cut off his head. In this version of the scene, Judith and her maidservant are beheading Holofernes. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Artemisia Gentileschi “Judith and Maidservant With Head of Holofernes” ca. 1612-1613 ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Artemisia Gentileschi “Judith and Maidservant Beheading Holofernes” ca. 1625. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Caravaggio, “Judith Slaying Holofernes”, ca. 1599. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Lucas Cranach “Judith With Head of Holofernes”, 1530. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Michelangelo. Judith and Holofernes. 1508-1512. Fresco. Sistine Chapel. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Andrea Mantegna, Judith and Holofernes. c. 1495 EARLY ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Botticelli Discovery of the Body of Holofernes. c.1469-1470. Tempera on panel. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Judith Beheads Holofernes In Other Works, Too! Donatello, Judith and Holofernes, 1455-60. EARLY ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, a wealthy descendant of Pope Paul III, commissioned this ceiling fresco to celebrate the wedding of the cardinal’s brother. The title interprets the variety of earthly and divine love in classical mythology. Carracci arranged the scenes in a format resembling framed easel paintings on a wall, but here he painted them on the surfaces of a shallow curved vault. The Sistine Chapel ceiling, of course, comes in mind, although it is not an exact source. This type of simulation of easel painting for ceiling designed is called quadro riportato (transferred framed painting). Annibale Carracci Loves of the Gods, 1597-1601. ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque Giovanni Battista Gaulli, “Triumph in the Name of Jesus”, Church of Il Gesu, Rome, Italy, 1676-1679 ITALIAN BAROQUE ITALIAN BAROQUE Italian Baroque As the mother church of the Jesuit order, Il Gesu played a particularly prominent role in the CounterReformation. Gaulli’s compostion focuses on the joyful rise of spirits to Christ’s aura. In contrast, figures of the damned seem to plummet through the ceiling to the nave floor. Gaulli successfully combined architecture, painting and sculpture to create a dramatic work that celebrates the glory of Christ and His Church. Giovanni Battista Gaulli “Triumph in the Name of Jesus”, Church of Il Gesu, Rome, Italy 1676-1679 ITALIAN BAROQUE ITALIAN BAROQUE