astronaut essay SAM MARTIN

advertisement

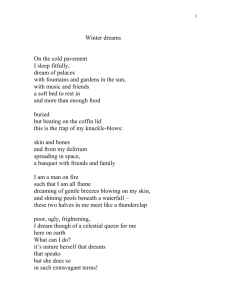

Samantha Martin A Wish Your Heart Makes I remember when my dream stared down at me and told me not to give up— that moment when I warded off “the real world” and dug myself deeper into my own version of it. It was my first meteor shower, the Perseids of August 2010, and I had been planning my viewing for weeks. But as the two nights drew nearer, the forecast grew less and less favorable. On the day of the first night, I drove to work absolutely heartbroken by the enormous cloud cover stretching across the sky. Still, I tried to stay positive. I don’t need a perfectly clear night, I told myself. Just a small pocket in the Eastern sky. But when I sat out on the deck that night, there wasn’t even a hint of a meteor. My parents were sympathetic the next morning, but I couldn’t bring myself to appreciate it. Already cleardarksky.com had re-­‐dashed my hopes, predicting an even worse second night. The second day dragged on even longer than the first, but I refused to lose hope. Once home, I told my surprised parents that yes, I was going to try again tonight, and yes, I had read the forecast, and yes, I knew what “heavy cloud cover” meant, and no, I didn’t care. They laughed and retreated to their corner of the house, probably quietly diagnosing me for a few hours before drifting off to sleep. So there I was, lying on the back lawn, staring at the evil clouds. The minutes slowly inched by until suddenly I saw something so extraordinary I thought I was dreaming: there, way over on the western horizon, was a small window of clear sky peeking through the clouds. I held my breath and watched it, using my highly untrained Jedi mind tricks to will it to move east. And it did. Before long, it had migrated across half the sky, centering itself perfectly on the meteor’s path. I could hardly breathe. Streaks hurtled across the night sky for a few glorious seconds each. I started to count them, but each new meteor brought such wonder that I kept forgetting what number I was on. Unfortunately, just as quickly as this window had appeared, it continued its path and disappeared over the other horizon. Content, I crawled into my warm bed and collapsed on the sheets. It didn’t matter that I had waited a combined 7 hours for those wondrous 15 minutes—the cold, the prickly grass, and the agonizing waiting all faded, replaced by the memory of the gold lights, flaring up and arcing across the sky, melting into infinity. Daring me to chase after them. Unfortunately, cloud cover isn’t the biggest enemy to late night observers— often, the far more menacing light pollution sends us to bed disappointed. Since my winters in Boston are therefore not filled with stargazing, I turn to the next best thing—learning. I wake up every morning to a new astronomical article on my homepage, and sometimes, if it’s a really good day, there’s a pop-­‐up notification about a newly discovered exo-­‐planet. I go to school and work hard all day, to get the grades I think I need to do more than just look at space—to actually go there. This naturally begs the question, why? Space travel is both terrifying and dangerous, and a zero-­‐gravity lifestyle takes more than just a little getting used to. The only explanation I have is that it’s my dream, and therefore I will do everything I can to make it my reality, too. But my current reality is hardly science fiction. I live in a household where MD’s outnumber coffee mugs, so I had thought I would be made fun of for my dream. And I was entirely right. I have to watch everything I say—one misused word, one faulty mental calculation, and they’re all laughing and asking me if NASA’s gone soft. But beneath the jokes and rolled eyes, I know I can still count on their support. Self-­‐doubt, however, is a whole different animal. It doesn’t laugh at you, it doesn’t make jokes. It is mostly silent, residing only deep in your heart, just waiting as it plants minuscule seeds of destruction. And then, without warning, it bursts forward and tries to choke you, whispering horrible things into your ear. Things like numbers—facts that can’t be argued. 99.5% is my personal favorite—the percent of astronaut applications that are turned down by NASA every two years. That’s 3,980 no’s to every 20 yes’s. In short, it’s a fantastically effective dream killer. Why put yourself through all those years of work, stress, and school just to ultimately be rejected (statistically speaking)? And here is where the self-­‐doubt pins you down— pointing out the near impossibility of dreams, it pressures you to disregard them entirely. Logically speaking, it would be better to cut your losses and return to the real world—or grow up, as some would say. But, as even Spock himself would agree, there are times when logic just isn’t the way to live your life. But even if you’ve combated the family expectations and challenged the self-­‐ doubt, dreams are simply not engineered to last in the real world. When you’re eight, it’s cute to want to be a Patriots linebacker; at eighteen, it’s time to grow up. So dreams blossom, fade, wither, and are soon replaced by others; it’s their natural life cycle. It’s one that should neither be ended too soon, nor dragged out too long. And so there is a delicate balance between holding fast to a dream, and grasping so tightly as to rob it of its worth. “Dream on, but don’t imagine they’ll all come true,” Billy Joel recommends (and gently warns). Dreams do come true; more often they don’t. But Billy Joel knows just as well as I do that getting what you dream about isn’t the point of dreaming at all. A dream’s true beauty isn’t its realization, but rather its very existence. We must dream and wish and long, because otherwise we end up not only stalled far below our potential, but also tragically convinced we’ve already reached it. If you dream huge, you will invariably end up in some place almost as big—maybe, in some ways, even bigger. And so I keep on dreaming. I nod along during diagnostic dinner conversations, pretending I understand how one would find, isolate, develop, and market a monoclonal antibody treatment for C. difficile (which, when I voiced my confusion, my mother clarified by saying “Oh, it’s Clostridium difficile, Sam,” to which I feigned sudden understanding). I listen to weekly messages from astronauts on the International Space Station, and take it to heart when Tracy Caldwell Dyson says to keep dreaming and join them someday. I look up whenever I can, and try to imagine what it would be like to look down. Those meteors are out there somewhere, and I fully intend to find them.