Forecasting Addictive Consumer Behaviour in Plastic Surgery: A

advertisement

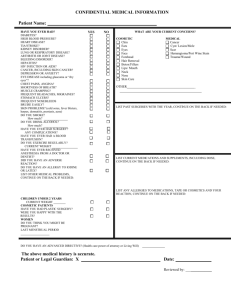

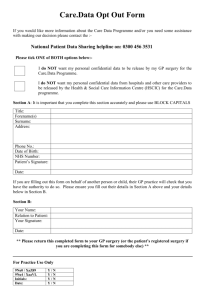

1 Forecasting Addictive Consumer Behaviour in Plastic Surgery: A Case Study in Vietnam Abstract Studies in Vietnam and other countries reveal that the number consumers willing to consider cosmetic surgery has increased. The purpose of this paper is to stimulate a research agenda by illuminating a key empirical issue on forecasting deviant consumer behaviour in Vietnam in relation to aspects of cosmetic surgery. Questions considered, include; what are the factors that affect consumers’ experiences and consumer’s addictive behaviour after undergoing plastic surgery? What is the probability of becoming addicted to or retaking cosmetic or plastic surgery? Do demographics have any bearing? Primary data was collected from surveys and questionnaires distributed to both female and male consumers. The respondents either have had plastic surgery or are expected to have plastic surgery. The findings indicate that self-image and self-esteem are the most important factors influencing addictive consumer behaviour. Other factors such as demography and psychological aspects are also increasingly important but not are not as powerful an influence. While the Logit model reveals that a married consumer is 8.92 times more likely to repeat cosmetic surgery than a single consumer. Similarly, a younger consumer is 5.11 times more likely to repeat cosmetic surgery than an older consumer. This finding carries strategic implications for plastic surgery marketing. 2 1. Introduction Literature (Kvalem et al., 2006; Fox, 1997) indicates that more people are dissatisfied with their physical appearance (Appendix 2). Approximately 65,000 surgical cosmetic procedures were performed in the UK in 2008 (MNT, 2013), with breast enlargement being the most popular, followed by facial surgery, rhinoplasty (nose alteration), liposuction, and face-lifts. The prevalence of plastic surgery is not surprising as it is the oldest of the healing arts in history. Alas, this search for perfection has created addictive behaviour in relation to cosmetic surgery (Schouten, 1991). In this study, plastic surgery was characterised as deviant behaviour because the sample comprise the respondents who had plastic surgery on multiple occasions (repeat patients) as well as who are expected to have repeat plastic surgery in the future. Hence, this research will forecast this addictive consumer behaviour. Although the literature (Dowling, 2013; ABCS, 2013; Costhetics, 2011) indicates a difference between plastic and cosmetic surgery, this study employs the terms interchangeably. Following relevant literature (Fisk et al, 2010; Krych, 1989; Powers, 1993), we define deviant consumer behaviour as addictive behaviour, which differs from the “normal” standard. Although the discourse on deviant or addictive behaviour by consumers is acknowledged in relevant literature (Workman & Paper, 2010; Fisk et al, 2010; Lohr, 2009; Fullerton and Punj, 1997) the subject has not been prioritised in consumer research (Harris and Reynolds, 2003; Fullerton & Punj, 1997). The behaviour is similar to substance abusers because of inability to control their addictive purchasing habit (Black, 2007). Unfortunately, most research on consumer deviant behaviour relates to substance addiction (Faber et.al, 1995; Hirschman, 1993), which has focused attention on the damage that consumers can inflict on themselves, but does not evaluate the probability of the addictive behaviour. Hence, although the subject has become a stimulating area of research due to its psychological and financial impacts on markets and consumers (Fullerton and Punj, 1993; Harris and Reynolds, 2003), there are very limited empirical studies on the subject. Accordingly, our overall understanding of deviant consumer behaviour in cosmetic surgery remains limited. Therefore, it is intended, that this study will fill a gap in the relevant literature, and address topics such as the cultural values embodied in a developing country such as Vietnam. The limitations of this study are that, since the research was carried out in Vietnam, the findings of this research may not be germane to other countries and the limitations of a small sample (as a case study). Accordingly, this paper aims to answer several research questions such as: 1) What are the internal and external factors that affect consumers’ experiences, and what aspects affect the consumer’s addictive behaviour after undergoing plastic surgery? 2) What is the probability of or how likely is a consumer to become addicted to or retake cosmetic or plastic surgery? 2. Literature Review The term ‘plastic surgery’ was coined by Vongraffe in 1818. The word plastic is derived from the Greek word ‘plastickos’ which means to create, to shape, and to mould. Dhanraj (2006) defined plastic surgery as a multifaceted speciality that combines form, function, technique, and principle where deformities and defects of the skin and underlying structures are dealt with. It is also known as a problem solving speciality, as every patient presents a challenging problem requiring a unique solution to permanently change a person’s physical appearance but not for medical reasons. Contrary to plastic surgery, cosmetic surgery is carried out to please the eye of the beholder (Harper, Phillips and Gallagher, 2005). Around the middle of the century, concern about ageing, combined with a desire to highlight ethnic indicators, (e.g. adding a crease to the upper eyelid of Asians), created a wider demand for surgical help to improve appearance, and physicians eventually accepted cosmetic surgery as a legitimate treatment. In the 21st century, these “normalization” alterations include liposuction (to remove fat from a body to make it slim), 3 rhinoplasty (to change a nose that stigmatizes an individual), Botox (to remove wrinkles and signs of age), collagen injections, and breast augmentation (to restore youth or enhance beauty). Boyle (2012) indicates that the driving force behind the increase in demand for cosmetic surgery is the ageing profile and a reflection of the desire of people to stay young and continue to have a good social image. With beauty no longer restricted to being a woman’s forte, men have also started to explore the advantages offered by cosmetic therapy (Kennard, 2007). Overall it can be predicted that the market for cosmetic surgery is set to grow with an increasing demand among both men and women (Appendix 1) as it incorporates both health benefits as well as the modern desire to look young and attractive for as long as possible (Beech and Sheehan,1996). Since the early 1990s, the demand for cosmetic surgery has also soared in Vietnam (ICL. 2013). Since Vietnam has turned a kind-eye to Western fashion and its way-of-life, the cosmetic surgery options have increased dramatically, fuelled by demand from the burgeoning middle class (ICL. 2013). Nowadays wealthy Vietnamese, rather than going abroad, stay at home to have rhinoplasty (nose job) and take advantage of Vietnamese surgeons’ competence and low prices (Phụ Nữ Online, 2010; Malo, 2007). Plastic surgery costs in Vietnam are estimated to be approximately 70% lower than those in developed markets such as the US or Israel. Recent figures show that demand for cosmetic surgery as well as addictive behaviour in Vietnam continues to soar, with 53 private clinics now licensed in the city (Cuong, 2013; Malo, 2007). According to Vnexpress (2010), of these 53 licensed facilities, 45 are specialized clinics, while eight are general hospitals that offer plastic surgery services. 3. Research Methodology Quantitative analysis was employed in this study using correlation analysis and the Logit model. The Logit model is a form of regression, which is used when the dependent is a dichotomy and the independents are continuous variables, categorical variables or both. Justification for using a Logit model is to estimate the probability of a certain occurrence of consumer addictive behaviour based on several predictor variables such as respondents demographic characteristics and other attitudinal scores (Appendix 3, Survey Questionnaires). The Logit model has been used increasingly and successfully in the field of marketing and management (Lange, 2010; McCarty and Hastak, 2007). In this research, a research question is directed to predict a dichotomous outcome of consumer addictive behaviour such as whether a consumer is likely to undertake additional cosmetic surgery in the future. Although this research question could be answered conventionally using an ordinary regression with an ordinary least squares (OLSQ) technique, it was found to be less robust for handling dichotomous outcomes due to inherent statistical assumptions such as linearity, normality and continuity (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Algebraically, a Logit (log odds) function of π can be given by the following algebraic equations: 3.1 π odds = π −1 π log it( π) = log 1− π 3.2 log it( π ) = log( π ) − log(1 − π ) 3.3 The dependent variable in a Logit model is dichotomous. It takes the value one with a probability of success π, or value zero with a probability of failure of 1-π. In the above equations, the base of the logarithm function used is ten; however, the natural logarithm (3.4) is the most frequently used in empirical literature (Agresti, 1996). 4 3.4 ln( π) = ln( π) − ln(1 − π) Accordingly, the Logit model of any number π can be provided algebraically by the following equations: 3.5 π log it(π) = ln π −1 3.6 π ln = δ0 + δ1X1 + δ2 X 2 π −1 Following the equations, 3.5 and 3.6, relevant empirical literature (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000) reveal that a simple Logit model (with a single predictor variable) can take on the following forms: 3.7 eδ +δ X π= 0 1+ e 1 δ0 +δ1X Where π stands for the probability that the dependent variable equals one, δ0 for constant, δ1 for a parameter coefficient of X and e for the base of the natural logarithm. One hundred and fifty survey questionnaires were sent to Vietnam and distributed to clustered local participants. The participants were selected by using a cluster random sampling technique. A cluster technique was used because a list of the members of a population could not be obtained but a list of clusters of the population were obtainable from the clinics or centres of plastic surgery in Vietnam. Accordingly, it is more economical rather than stratified random sampling (Lohr, 2009). The participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality, which had increased significantly their participation and response rates. After filtering the questionnaires and removing unusable and blank answers, 122 usable questionnaires remained. The questions (Appendix 3) asked in the survey are based on relevant literature on consumer behaviour (Solomon, 2012) and based on selfconcept, on theories regarding the factors influencing consumers’ decisions to undergo cosmetic surgery, and on consumer satisfaction with plastic surgery. 4. Empirical Findings The findings indicate that the majority of respondents were between 26 and 54 years old (80.9%). Previous studies (Kalfus, 2012) indicated the majority of female respondents who had undergone cosmetic surgery were between 18 and 44 years old. Other female respondents said they would have plastic surgery if cost were not an issue. Similarly, a study conducted by Asaps (2011) found that in a sample of 1,000 women between the ages 18 and 30, 72% indicated they wanted to have cosmetic surgery; 49% said they planned to have work done at some point in the near future. In another study, Agovino (2007) found that women tend to begin visiting plastic surgeons when they are in their late 30s and early 40s to restore their youthful appearance with procedures such as Botox shots. Hence, the explanation of the above result is that the findings from Vietnam are in line with earlier findings that typical consumers of cosmetic surgery are people in the middle age range, typically between 26 and 34 years old, who want to avoid the effects of ageing. The findings reveal that the majority of respondents (64.1%) did not feel satisfied with their facial features, including the nose, eyes, lips, and the whole face. The breasts were the second feature they were most dis-satisfied with, accounting for 15.8%, followed by 7.5% who did not feel satisfied with their skin. Dissatisfaction with the stomach accounted for 5.8%, while 1.7% were unhappy with their legs. Only 0.8% or one respondent was dissatisfied with his or her neck. Looking at past studies (Châu, 2011), the reason many respondents thought that their faces were unattractive is because of the environmental atmosphere in Vietnam. 5 The findings show that 60.8% of the respondents had surgery on their faces, including lips, cheek, chin, nose, and hair (60.8% or 73 respondents). A further 20 respondents (16.7%) had breast augmentations, while eight respondents (6.7%) had liposuction and seven (5.8%) underwent dermabrasion. Scar revisions were performed on five respondents (4.2%), three respondents (2.5%) had a tummy tuck, two respondents (1.7%) underwent penis enhancement surgery, and two others (1.7%) had other types of surgery. The results of this study support Roald and Skolleborg’s (2009) findings that the numbers of facial surgery are increasing rapidly. In their 2011 study, they found that plastic surgeons reported an increase in the numbers of Hispanic, Asian-American and African-American patients. Of the four most popular cosmetic procedures, African-Americans and Hispanics were most likely to have received rhinoplasty (88%), which is a 10% increase from 2010). Asian-Americans were most likely to have undergone either blepharoplasty (56%) or rhinoplasty (35%). One explanation for this result is that most Asian people do not have a “proper” face, especially with regard to their nose and cheeks, and the majority of plastic surgical procedures concentrate on the face (Joethy and Tan, 2011). The findings reveal that friends and family had the greatest influence on consumers who underwent plastic surgery (36.7% or 44 respondents were influenced by friends and 25% or 30 respondents by family). Twenty-five respondents (20.8%) indicated that they had personal reasons for having surgery. Past experience, was a reason given by 13.3% or 16 respondents. The last influencing factor was media/magazines/celebrities, which accounted for 4.2% or five respondents, who had undergone surgery because of media and celebrity influences. Interestingly, the results of this study are not in line with those of a previous study (Shaffer, 2010) about the factors that influence people to undergo plastic surgery. For example, the influence of celebrities in Vietnam is low compared with other industrialized or European countries. Shaffer (2010) pointed out that celebrities these days are far more open about their plastic surgeries, and the ones who do not need any work are still inspiring to people who are unhappy about their looks. The explanation for this result is that the celebrities in Vietnam are not used to plastic surgery and that not many of them have had it, or have only undergone small and simple nonsurgical operations, which are hard to notice, so, celebrities in Vietnam did not have a great influence on consumers’ decisions regarding plastic surgery. The majority of Vietnamese respondents (64.1% or 77 respondents) did not think that a particular celebrity inspired them to undergo surgical procedures. Twenty-five respondents (20.8% or 25) think that they are influenced by celebrities, while 15% or 18 respondents gave no opinion. Compared with findings from similar studies in the US and in some European countries, Toscano’s study (2010) indicates that Hollywood celebrities are a big influence to most people when considering cosmetic surgery. The results reveal that the variables X1, X4, X11, X18 are significant predictors of Q16, or of how likely a consumer is to carry out addictive behaviour. Based on SPSS results, the multiplicative form of the model can be rewritten as follows: 4.1 π 1.631−0.831X 1− π =e 1 π = e 2.188 −0.773X 4 1− π 4.2 Ln (π/1-π) is known in the literature (Agresti, 1996) as the log-odds and (π/1-π) as the odds. By using this simple Logit model of 4.1 (one explanatory variable of the respondents’ age, whether the respondent is younger or older than 34 years), the odds that a subject of given classification can be predicted accordingly. The finding indicates that a younger consumer (X1=0) is 5.11 times more likely to repeat cosmetic surgery than an older consumer. Whilst, an older consumer (X1=1) is only 2.23 times more likely to repeat the surgery. While the Logit model of 4.2 reveals that a married consumer (X4=0) is 8.92 times more likely to repeat cosmetic surgery than a single consumer. Whilst, a single consumer (X4=1) is only 4.12 times more likely to repeat the surgery. Using additional explanatory variables, the Logit model can be re-produced accordingly: 6 ln π = 0.223 − 0.176X1 + 0.311X 4 + 0.06X11 + 0.877X18 1− π 4.3 This equation 4.3 tells us that increasing age decreases (-0.176) the log odds of repeating cosmetic surgery (ceteris paribus, holding other variables constant). This finding seems to contradict findings in earlier studies (Agovino, 2007) which reveal that the older the people are, the more likely they are to retake cosmetic surgery to maintain their beauty and counteract the effects of ageing. The result reveals that a greater number of young people are not satisfied with their physical appearance compared to the older generation. Interestingly, the findings show that being married increases the log odds (+0.311) of having more cosmetic surgery in the future (ceteris paribus). According to Ethridge’s study (2012), there has been a rise in the number of married women getting plastic surgery. The majority are 32 to 40 years old, were married at a young age (in their early 20s), and have one or two children. In addition, Beckman (2012) revealed that more married women than ever before are having plastic surgery, compared to married men. One reason for this is that they feel pressure to keep their husbands happy. Some respondents indicate that they are tweaking their looks to feel better about themselves. Hence, women may have all the right motives, including doing it for herself and for her husband, since, in a healthy relationship, both individuals have a stake in the plastic surgery process. In addition, a study by Edgerton et al. (1985) indicated that the typical facelift patient has been classified as a married, upper-middle class, socially active woman who is grateful for and enthusiastic about her enhanced appearance. A Pearson product-moment correlation (r) was also computed to assess the relationship between the number of times consumers have had plastic surgery and the consumers’ satisfaction levels after surgery (r= 36.20%, Sig. <0.05). The findings indicate that the more times people have plastic surgery, the more satisfied they feel about themselves. This seems to support the hypothesis of addictive consumer behaviour. The theoretical explanation relates to how the consumers define the concept of self-esteem (Soest, 2006). For example, when a consumer has relatively low self-esteem before surgery, after having the plastic surgery, they are happy with the results; they believe that there is now nothing wrong with them. On the other hand, the findings support the hypothesis that people with lower self-esteem think that cosmetic surgery will give them more confidence and selfesteem (Edmonds, 2007) and so they believe more plastic surgery will make them happier, since they will be perfect. The model of 4.3 reveals that the respondents’ perception towards feeling more beautiful and confident have significantly affected the likelihood of them retaking cosmetic surgery. That is, being more confident after cosmetic surgery increases the log odds (+0.877) of having more cosmetic surgery in the future (ceteris paribus). All parameter coefficients of the Logit model of 4.3 are significant at a 1% level as indicated by Wald statistics. In addition, knowing more people (who have had cosmetic surgery) increases (+0.006) the log odds of someone repeating plastic surgery. This finding is supported by the Pearson product-moment correlation, which indicated a significant relationship between the consumers’ self-confidence after cosmetic surgery and their intention to undergo more surgery (r= 0.695, Sig. <0.05). The findings indicate a positive correlation between the level of consumer satisfaction after having plastic surgery and the intention to have more surgery in the future. According to Emievil (2010), when consumers are not satisfied with their appearance after having plastic surgery, they might try alternative surgeries in the future. However, previous research, such as that by Teitelbaum (2004), contradicts Emievil’s study. People want to be perfect and are not satisfied with themselves, so tend to have increasingly higher demands and undergo more plastic surgery in an attempt to reach their target of perfection. Juxtaposing the two studies reveals the differences in relation to the findings. This finding carries strategic implications for plastic surgery marketing, for example, the surgical institutions should focus on a specific segment of consumers such as repeat buyers, married female and younger consumers. 7 Appendix 1 Global Cosmetic Surgery Market Analysis by Segment 2006-2013 (in £ Billion) Source: Adapted from BCC Research (2009) Appendix 2 Before and After Cosmetic Surgery Source: Adapted from Pandey et al. (2012) 8 Appendix 3 1) What is your age? 2) What is your gender? 3) Where do you live? 4) What is your marital status? 5) What is the highest level of education you have completed? 6) What is your monthly income? 7) To what extent do you agree with the statement “Beauty is more important than brains”? 8) To what extent do you agree with this statement “You feel self-confident about your appearance”. 9) What do you feel is the most unattractive feature on your body? 10) To what extent do you agree with this statement “Ageing will influence your beauty”. 11) How many people who have had a cosmetic surgical procedure do you know? 12) Which has the largest influence in your choice to do the cosmetic surgery? 13) To what extent do you agree with this statement “A particular celebrity inspires you to do the procedure”. 14) To what extent do you agree with this statement “You are really worried before doing the cosmetic surgical procedure”. 15) Where did you have the cosmetic surgical procedure? 16) How many times have you had a plastic surgical procedure? 17) What types of plastic surgery have you undergone? 18) To what extent do you agree with this statement “I feel more beautiful and self-confident after having a cosmetic surgical procedure”. 19) To what extent do you agree with this statement “You would feel embarrassed if someone knew that you had undergone a cosmetic surgical procedure before”. 20) To what extent do you agree with this statement ”If you could go back time, you would not have had a cosmetic surgical procedure”. 21) To what extent do you agree with this statement “Cosmetic surgery is harmful to your health”. 22) To what extent do you agree with this statement “You will have a cosmetic surgical procedure in the future”. 9 References ABCS. (2013). Understanding the difference between “cosmetic” and “plastic” surgery, Accessed electronically on 2 December 2012 from http://www.americanboardcosmeticsurgery.org/How-We-Help/cosmetic-surgery-vs-plasticsurgery.html Agresti, A. (1996). An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, New York: Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-11338-7. Agovino, T. (2007). More men having plastic surgery, Edition: 5th December, Accessed Electronically on 27th April from http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-204_162-623083.html Asaps (American Society of Plastic Surgeons) (2011). Surveys find many young women begin planning plastic surgeries in teens, edition: 19th September, Accessed electronically on 27th April from http://www.surgery.org/consumers/plastic-surgery-news-briefs/surveys-findyoung-women-planning-plastic-surgeries-teens-1035572 ASPS (American Society of Plastic Surgeons). 2012. The History of Plastic Surgery, Accessed electronically on 7 May from http://www.surgery.org Beckman, J. 2012. Dr. James Beckman Answers Your Questions About Plastic Surgery, Accessed electronically on 7 April 2012 from http://theskinny.therapon.com/dr-james-beckmananswers-your-questions-about-plastic-surgery/ Black, D. W. (2007). “A Review of Compulsive Buying Disorder,” World Psychiatry, Vol. 6, Issue 1, February Edition, page 14-18. BCC Research. 2009. “Cosmetic Surgery Markets: Products and Services”, Research Report, July Edition, Accessed electronically on 11 December 2012 from http://www.reportlinker.com/p0132720-summary/Cosmetic-Surgery-Markets-Products-andServices.html Boyle, C. (2012). Implant Scare at Tough Time for Cosmetic Surgery Industry, Edition: 9th January, Accessed Electronically on 30 April from http://www.cnbc.com/id/45924571/Implant_Scare_at_Tough_Time_for_Cosmetic_Surgery_I ndustry Châu, U. (2011). Nâng mũi bọc sụn không cần cắt chỉ, Edition: 29th October, Accessed Electronically on 28th April from http://vnexpress.net/gl/suc-khoe/lam-dep/2011/10/nangmui-boc-sun-khong-can-cat-chi/ Costhetics. 2011. The difference between plastic and cosmetic surgery, Accessed electronically on 4 January 2013 from http://www.costhetics.com.au/news/the-difference-between-plastic-andcosmetic-surgery Cuong, N.X. 2013. Vietnam Cosmetic Surgery – Asia Cosmetic Surgery, Accessed electronically on 23 March 2012 from http://www.thammysaigon.com/en/Index.aspx Dhanraj, P. (2006). Plastic Surgery Made Easy, New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical. Dowling, N.A., Jackson, A.C., and Honigman, R.J. (2013). “A Comparison of the Psychological Outcomes of Cosmetic Surgical Procedures”, Plastic Surgery: An International Journal, Vol. 2013, Article ID 979486, page 1-9, IBIMA Publishing, http://www.ibimapublishing.com/journals/PSIJ/psij.html Drennan, J. C., Drennan, P. and Keeffe, D. A. (2007). Research in Consumer Misbehaviour: A Simulation Game Approach, Conference Proceedings, 2007Australia And New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference (ANZMAC), Dunedin, New Zealand. Edgerton, M.T., Webb, W.L. and Slaughter R. 1985. “Surgical results and psychosocial changes following rhytidectomy”, Plastic Reconstruction Journal, Vol. 33, pp.503–14. Edmonds, A. (2007) “The poor have the right to be beautiful: Cosmetic surgery in neoliberal Brazil”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 13, pp. 363-381. Emievil (2010). Nine things you should know before having a cosmetic surgery, Accessed Electronically on 29th April from http://emievil.hubpages.com/hub/9-Things-You-ShouldKnow-Before-Having-a-Cosmetic-Surgery 10 Ethridge, T. 2012. Ethridge Plastic Surgery, Accessed electronically on 30 May 2012 from http://drethridge.com/meetthedoctor.html Finley, J. M. (1991). Considering Plastic Surgery, Gretna, Publisher: Pelican. Fisk, R., Grove, S., Harris, L., Keefe, D., Daunt, K. and Russel-Bennet, R. 2010. “Customers behaving badly: a state of the art review, research agenda and implications for practitioners”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 417–429. Fox, K. 1997. “Mirror, mirror: Why we look into the mirror”, A summary of research findings on body image, Publisher: Social Issues Research Centre (SIRC), Accessed electronically on 14 December 2012 from http://www.sirc.org/publik/mirror.html Fullerton, R.A. and Punj, G. (1997). “What Is Consumer Misbehavior?”, in Brucks, M. and MacInnis, D.J. Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 24, pp. 336-339, Publisher: Association for Consumer Research. Haiken, E. 1997. Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery, Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press. Harper, P. R., Phillips, S. and Gallagher, J. E. (2005). Geographical Simulation, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Harris, L. C., Reynolds, K. L. (2003). The consequences of dysfunctional customer behaviour, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, page 144-161. Hiquera, V. C. (2006). Plastic Surgery Addiction – A body image problem within our society, Edition: 18th August, Accessed Electronically on 28th April from http://voices.yahoo.com/plastic-surgery-addiction-body-image-problem-within-64753.html Hosmer, D.W. and Lemeshow, S. 2000. Applied Logistic Regression, Second Edition, New Jersey, Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN: 0-471-72214-6. doi.wiley.com/10.1002/0471722146.refs ICL. (2013). Vietnam offers latest cosmetic surgery technology, ICL (Intuition Communication Ltd.), Accessed electronically on 3 May 2012 from http://www.treatmentabroad.com/medical-tourism/news/november-2007/vietnam-offerslatest-cosmetic-surgery-tec353/ Jessica, E. (2009).” Cosmetic Surgery: Balancing Inner Beauty and Outer Beauty”, Inner Beauty, Edition, 4th December, Accessed Electronically on 28th April from http://dallasbeautiful.com/cosmetic-surgery-balancing-inner-beauty-and-outer-beauty Kalfus, M. (2012). Twelve plastic surgery trends for 2012, Accessed electronically on 12 May 2012 from http://www.ocregister.com/articles/surgery-334975-plastic-responses.html Kennard, J. (2007). Male Cosmetic Surgery, Edition: 2nd September, Accessed Electronically on 30th April from http://menshealth.about.com/cs/surgery/a/cosmetic.htm Krych, R. (1989). “Abnormal Consumer Behavior: A Model of Addictive Behaviors”, in Srull, T.K (Ed.). Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 16, Publisher: Association for Consumer Research, page 745-748. Kvalem, I. L., Von soest, T.R., Einar, H. and Skolleborg, K.C. (2006). “The interplay of personality and negative comments about appearance in predicting body image”, Body image, ISSN 1740-1445, Vol. 3, pp. 263- 273. Lange, T. (2010). “Culture and Life Satisfaction in Developed and Less Developed Countries”, Applied Economics Letters, Vol. 17, No. 9, pp. 901-906, Routledge, London. Lantos, G. P. (2010). Consumer Behaviour in Action: Real-life Applications for Marketing Managers, Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. Lees, M., Gerson, J. and Michel, L. (2001). Skin Care: How to save your skin, Albany: Thomson. Lindbridridge, A. and Wang, C. 2008. “Saving face in china; modernization parental pressure and plastic surgery”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 7, No. 6, pp. 496 – 508. Lohr, S. L. 2009. Sampling: Design and Analysis”, Advanced Series, 2nd Edition, Publisher: Cengage Learning; 2 Edition (December 9, 2009), ISBN-10: 0495105279 Malo, S. 2007. Plastic surgery a dangerous business in Vietnam, Accessed electronically on 7 June 2012,from http://www.thingsasian.com/stories-photos/20714 11 McCarty, J.A. and Hastak, H. 2007. Segmentation approaches in data-mining: A comparison of RFM, CHAID, and Logistic regression, Journal of Business Research, Volume 60, Issue 6, June 2007, Pages 656-662. MNT. 2013. What Is Cosmetic Surgery? What Is Plastic Surgery?, MNT (Medical News Today), Accessed electronically on 7 January 2013 from http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/155757.php Pandey, N., Pandey, B. and Prasad, P. 2012. World of Female, Accessed electronically on 14 May 2012 from Phụnữ Online (2010). Phẫu Thuật Thẫm Mỹ: “ Dục tốc bất đạt, Edition: 29th December, Accessed electronically on 30th April from http://us.24h.com.vn/tham-my-vien/phau-thuat-tham-myduc-toc-bat-dat-c331a347023.html Powers, K.I. (1993). “A Longitudinal Examination of Addictive Consumption: Its Behavioral and Psychological Pattern and Consequences”, in McAlister, L. and Rothschild, M.L. (Editors). 1993. Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 20, pages: 405-412, Publisher: Association for Consumer Research. Saraf, S. (2007). “Millard’s 33 Commandments of Plastic Surgery”, the internet Journal of Plastic Surgery, Vol. 4, No. 1. Schouten, J. W. 1991. “Selves in Transition: Symbolic Consumption in Personal Rites of Passage and Identity Reconstruction”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, March Edition, pp. 412-425. Soest, T., Kvalem, I.L.,Skolleborg, K.C. and Roald, H.E. (2006). “Psychosocial factors predicting the motivation to undergo cosmetic surgery”, Plastic and reconstructive surgery (1963), ISSN 0032-1052, Vol. 117, Issue 1, pp. 51- 62. Solomon, M. 2012. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, New Jersey, Publisher: Prentice Hall, 10 edition, January 6, ISBN-10: 0132671840 Tabachnick, B.G. and Linda S. Fidell, L.S. 2001. Using Multivariate Statistics, Edition 4, Publisher: Allyn and Bacon, ISBN-0321056779. Teitelbaum, S. (2004). Cohesive Gel Breast Implants, Edition: 23rd September, Accessed Electronically on 5 May 2012 from http://www.breastimplantsusa.com/steventeitelbaum/articles.htm Vnexpress. (2010). Plastic Surgery, Accessed electronically on 30 May 2012, from http://vnexpress.net/ Workman, L. and Paper, D. 2010. “Compulsive Buying: A Theoretical Framework”, The Journal of Business Inquiry, Vol. 9, No. 1, page 89-126, ISSN 2155-4056 (print), ISSN 2155-4072 (online). Xuvn. 2013. Plastic Surgery in Vietnam - Cosmetic Surgery in Vietnam, Accessed electronically on 2 February 2012 from http://www.xuvn.com/beautifyfood/plastic%20surgery/vietnamese_plastic_surgery.htm