Determinants of the Canadian-U.S. Basis for Cash Fed Cattle and

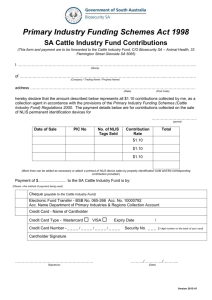

advertisement