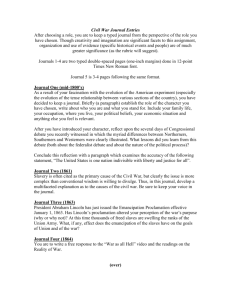

Abraham Lincoln: Unfinished Legacy

advertisement