ELIZABETH BISHOP PHOTOGRAPHIC POETICS THE

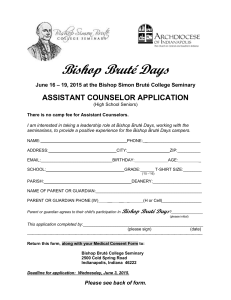

advertisement