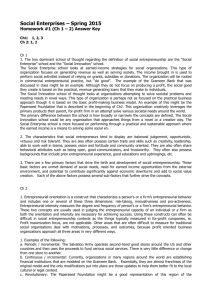

Opportunity Identification and Exploitation: A

advertisement