ARTICLES - Harvard Law Review

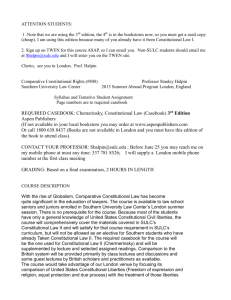

advertisement